Contemporary artist and performer David Liver recently created Voice Over, an online magazine supported by the Intercultural Cities Programme of the Council of Europe. It engages with current critical discourse from the perspective of the artist and offers alternative narratives to ongoing social and political discussions that take place in- and outside of institutional walls. The first issue Conflict was curated together with artist Jimmie Durham and the second issue Bad AI features work by poet and artist Kenneth Goldsmith. The Compendium reached out to Liver to discuss the motivations and aims of his ambitious and challenging project.

Voice Over is a magazine that addresses cultural issues to the institutional representatives. Why this target audience and what motivated you to initiate the series?

I would say that this is a contextual audience made of people working and living within the “bubble” of the European institutions. They are where Voice Over takes the stage. By choosing the Council of Europe, and more specifically ICC (Intercultural Cities Programme), as the tribune from where we engage in the discussion, the representatives and their whole hive are de facto our first natural audience. Voice Over, however, is out there, possibly for everyone who is interested in reading artists’ opinions on current issues.

The question is not for whom but from where one speaks. The great Christoph Schlingensief said: “Art ought to be more political and politics more artful.”As an artist I’ve always been questioning a certain drive for disruptive and provocative forms of discourse, their political background and what they are actually meant to be.

At some point the question took so much place in my life that I decided to talk about it with Jimmie Durham, an artist that certainly had a strong impact on me. So when I launched Voice Over, I decided to kickstart it with him. We edited our conversation into something more à propos and less personal and around that, I built the rest of the magazine.

The problem is that whatever artists do or manifest, they do it within a very small, semi-protected context, in front of a bored as well as familiar crowd. That doesn’t obliterate their work but somehow the political discourse falls in the absence of any discourse at all. As context is everything, I imagined bringing the artists’ voices into the house of political discourse. But then my provocative drive took over with a more engaged baseline: what if we could put our discourses into the European institution’s mouth? And this is why each issue of the magazine starts with an article that sets the stage, positioning us in a specific place: the hémicycle.

How is the artistic perspective different in discussions on themes that you approach with the magazine?

Voice Over address the major themes of ICC at the Council of Europe: emigration, discrimination, AI bias, gender related issues, gentrification and so on.

There is a certain degree of political background or drive in the making of art, a certain way of standing up and positioning ourselves. But unlike politics, art is selfish and not accountable. Art intervenes in the world by creating pieces of language that weren’t there before, or by making things happen when they didn’t happen yet. Art tries to make sense of everything, mistakes are welcome, failure doesn’t really matter much, and all of the structured set of rules that one can be confronted with can be dismantled and reassembled in another language, in a different landscape, with new correlated policies.

Nobody needs an artist’s perspective on the discourse, but maybe someone out there can take advantage of these perspectives. They can be a useful tool for looking at serious things that, once deconstructed, reveal a completely new point of view on the subject. In other words, artists make language out of language, and this seems to me to be a good practice when trying to feed the discourse.

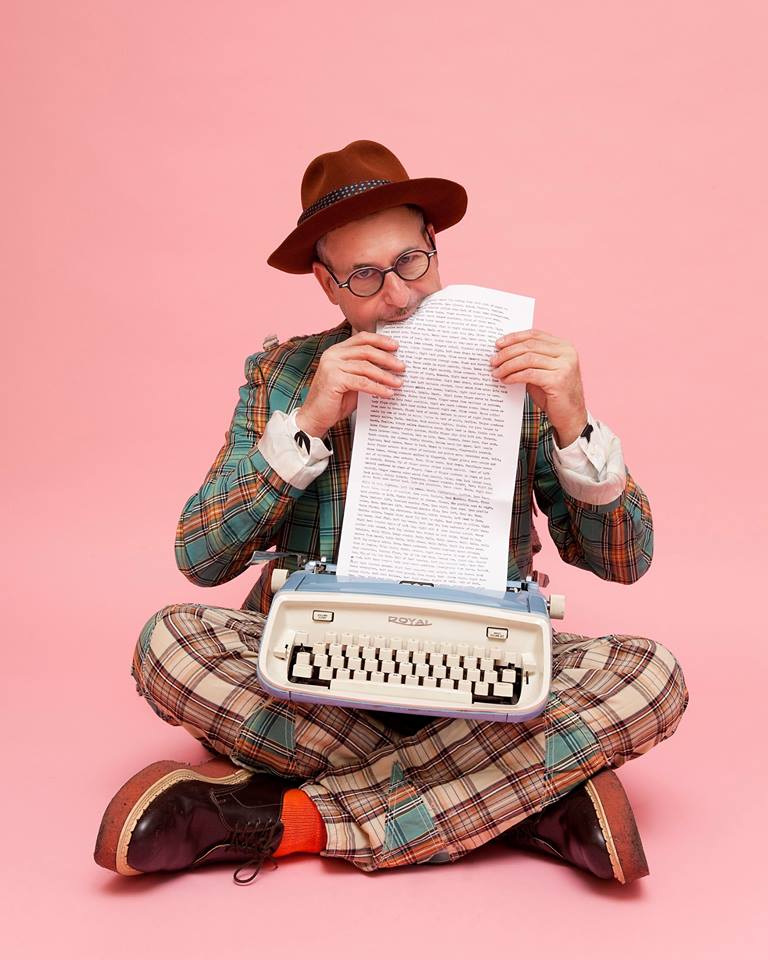

Jimmie Durham – In Europe | By Maria Thereza Alves

Kenneth Goldsmith | By Olivia Locher

One of the aims of Voice Over is to urge “readers and writers to reach beyond their usual notions of culture and Europe.” Why do you think this is important?

Not so many people actually know about European institutions, the way they are organised or their positioning. The who is who of Europe is still a bit blurry, generally speaking and the EU should absolutely do a lot more in order to make all of us understand it better. Then again, not so many people actually know about arts and culture either. Most of us tend to confuse them. Voice Over is not a school book, we can’t do anything about that, but we can produce some kind of “good noise”, some bug in the perception of European institutions and of arts in order to reframe this perception and hopefully ignite some interest that would eventually lead to a different place.

The next issue is a good example of this. It is about artificial intelligence (whatever it means). This is actually a hot issue currently at hand at the Council of Europe: how to define it, how to control the use and the conception of it, how to respond to the bias’s manifested with and through it and so on.

Voice Over takes a different approach on the question of AI discrimination. We feature 15 paragraphs on Bad Ai by American poet and artist Kenneth Goldsmith who notoriously made massive use of data for his poetry. In this article, Goldsmith raises the question of AI naivety: trying too hard to be good. He suggests re-bugging and re-writing of the bots for a perfected intelligence. The piece is completed by a few more articles, such as a very interesting interview of Florent Delval with researcher Os Keyes. One of the many things that came out of this issue is that the AI programmers keep training intelligences with incomplete and naive models and obsolete ideas of what intelligence is. The absolute avoidance of errors and incidents perpetrated by these high profiled tech guys looks a lot like a perfect metaphor (or even cause) of the dangerous AI’s discrimination problems.

Voice Over is produced by Urubu Films and the Intercultural Cities Programme at the Council of Europe. The issues Conflict and Bad AI are freely available here.

Main image: In Europe | By Jimmie Durham

Comments are closed.