1. Cultural policy system

Finland

Last update: March, 2017

The formation of Finnish national cultural policies

from the mid-19th century to the late 20th century can be roughly

divided into three stages:

The formation of Finnish national cultural policies

from the mid-19th century to the late 20th century can be roughly

divided into three stages:

- the period of the Patron State, from the 1860s to the 1960s;

- the arrival of the Welfare State and the articulation of explicit cultural policy objectives from the late 1960s to the 1980s; and

- the move beyond the Welfare State in the late 1990s.

Historically, four forces have shaped these developments:

- the civic movements which, despite linguistic and ideological divisions, contributed to the development of Finnish culture;

- the ambitions of the newly formed state to strengthen Finnish cultural identity, by central government policies promoting the arts and supporting artists;

- the commitment of municipalities (the basic units of Finnish local self-government) to provide cultural services for their citizens, to promote their citizen's interest in the arts, and encourage involvement in the amateur arts; and

- the growth of the national culture industries, which, to start with, were ready to foster the vitality of even less profitable genres in cultural production.

The foundations for Finnish national culture were laid and affirmed under the Russian Czarist regime (1809-1917) which, alongside the Senate of the autonomous Finnish Grand Duchy, was the patron of the evolving bilingual (Swedish and Finnish) artistic and cultural life. After independence, the new nation state took over the role of patron and continued to build a national identity and national unity. This identity was based on the cultural heritage stemming partly from the period of Russian rule, and partly from the period of earlier Swedish rule, which had lasted seven centuries. During the first four decades of independence, which saw a civil war and two wars with the Soviet Union, national unity and national identity became even more prioritised objectives of the state and, subsequently, also central principles in national cultural and arts policies. Other objectives, such as the promotion of creativity and enhancing participation and cultural democracy, started to gain ground in the 1960s and became integrated with other economic and social goals when the ideology of the social welfare state was more comprehensively adopted and implemented in the 1970s.

Public support for the arts and culture had expanded even before the advent of the social welfare state. The municipalities had gradually taken over the task of maintaining institutions of adult education and public libraries from the civic associations and the central government started to subsidise them on a regular basis. The role of the state in supporting these institutions was cemented by legislation in the 1920s. The joint financial responsibility of the state and the municipalities became one of the pillars of modern Finnish cultural policy.

The broader financial basis for public support of the arts, cultural institutions and cultural services was confirmed by legislation in the 1960s and 1970s. The system of artists' grants traces its legislative basis to the late 1960s and state support for municipal non-institutional cultural activities was set in legislation at the beginning of the 1980s.

Although some national institutions (especially the National Opera and the National Theatre) maintained their private legal status, the process of "étatisation" of Finnish cultural and art institutions accelerated in the 1970s and continued well into the 1990s. The institutions of higher education in the arts and the National Art Gallery became part of the state budgetary system and the former were granted the status of state universities. In parallel, local museums, theatres and orchestras also came under the budgetary control of the municipalities and, at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, their grants were organised as a subsystem within the new statutory state transfer (subsidy) system to municipalities. In addition to the new Financing Law, this also led to Laws on Museums, Theatres and Orchestras (1992). Only a few professional institutional theatres and orchestras (including the National Theatre and the National Opera) were left to be financed on a contractual discretionary basis.

The above overview suggests that historically the main instruments of Finnish cultural policy have been:

- direct financial support for the arts, artists and artistic creativity, including extensive systems of cultural and arts education and professional training of artists

- extensive public or non-profit ownership and joint financing of cultural and art institutions by the central government and the municipalities, including state ownership and until the end of 2012 licence-based and from 2013 taxation-based financing of the public service broadcasting company (Finnish Broadcasting Company Ltd., YLE);

- modest subsidies to the culture industries, especially to the press and cinema, and;

- active international cultural co-operation, traditionally in the spirit of cultural diplomacy; and, more recently, increasingly in search of success in international trade of cultural goods and services.

The first decade of the 21st century has seen a gradual transformation of Finnish society and Finnish commitment to the basic principles of the welfare state. The changes from the mid-1990s onwards have created, within the legal and administrative frameworks of the European Union, a new system of governance with distinct touches of neo liberal market orientation in the public sector. Although public cultural administration has been rather slow in reacting e.g. to the requirements of new public management, many other factors have shaped the conditions of artistic activities, cultural service systems and creative industries. Such factors are e.g. the enlarging of the European Union, new ways of coupling the arts and artists to the networked information society and creative economy, and the need to enhance the export of arts and cultural goods and services. The effects of these undercurrents have been partly interrupted, partly precipitated by financial crises and economic recessions in 1991-1993 and in 2009-2010.

In the early 2000s, neo-liberalism, in the guise of desetatisation, seems to have entered cultural policy through the backdoor of university reform enacted by all-comprehensive national university legislation. The new 2009 University Act extends the autonomy of universities by giving them an independent legal personality either as public corporations or as foundations operated partially under the old 1930 Foundation Act. The government has also taken definite steps to enforce closer ties than mere networking between universities in order to enhance their research productivity and contribution to the national economy and exports. This policy is reflected in the decision which administratively merged the biggest art university, the Helsinki University of Art and Design with the Helsinki University of Technology and the Helsinki School of Economics. The new super-university, named "the Aalto University", is financed thorough a foundation and the board of the foundation, consisting of national and international recognised researchers and artists and representatives of Finnish industry, has the final say as to the long term policy orientation of the university. The joint operations at the Aalto University were started on the 1 January 2010. Since the beginning of the 1990s there has been a long on-going process aimed at merging administratively the three other art universities, the Sibelius Academy of Music, the Academy of Fine Arts and the Theatre Academy. The merging of these three art academies into a University of the Arts Helsinki (http://www.uniarts.fi), including students, personnel and funds, took place on 1 January 2013.

Also, the changing civil and economic climate has given rise to a Finnish "foundation-boom", evident even in the cultural policy domain, especially since and during the government of 2011-2014 (prime minister Jyrki Katainen). It affected the above mentioned national cultural institutions also, as the government of prime minister Katainen launched action into turning the Finnish National Gallery into a foundation (see chapter 2.9). The FNG started operating as a foundation at the beginning of 2014. In addition, the Ministry of Education and Culture's subordinate Institute for Russia and Eastern Europe, was closed down and its duties were passed on to a newly established Cultura Foundation from January 2013 (see chapter 2.6).

The changes that took place in the late 1990s and at the beginning of the new millennium have somewhat decreased the role of the state and municipalities in the governance of culture and as direct financiers of artists, cultural services, voluntary organisations and cultural production. At the same time, the role of the public authorities in providing capital investment for cultural buildings and facilities and for professional education in the arts and culture has become increasingly prominent. In other words, public authorities invest in infrastructure and highly trained and qualified manpower but expect that cultural and art organisations and institutions finance an increasing share of their current costs with their own income or revenues from other sources. EU policies, especially the programmes financed within the context of the Structural Funds, have linked public cultural policies more closely to urban and regional development and social cohesion policies. It should be added that Finland has observed strictly the criteria of the budgetary discipline of the EU Stability and Growth Pact, which, together with the aftermath of the economic recession of 1991-1993, curtailed public spending, including spending on the arts and culture (for the effects of this, see chapter 2.1, chapter 3.1 and chapter 7).

At the beginning of April 2014 the government announced that the budget for the arts and culture (by the Ministry of Education and Culture) will be first reduced by 15 million EUR by the end of 2016 (5 million EUR in 2015 and 10 million EUR in 2016) and then during the two following years 2017 and 2018 by 15 million EUR per year. In addition it was announced that the profits from the National Lottery will decrease by 10 million EUR which means for the cultural sector a further 4.3 million EUR decrease in financing of cultural organisations in 2015. This source of funding has been very important for culture, but also for sports and youth activities

Main features of the current cultural policy model

As indicated in the previous history chapter, the Finnish cultural policy model reflects the overall values of a social welfare state. From the point of view of decision-making and administration the Finnish cultural policy model is – or at least until recent time has been – a model of horizontal and vertical decentralisation and arm's length implementation. On the level of the central government, a number of expert bodies and agencies advise the Ministry of Education and Culture and also implement agreed upon policies. Some of these bodies have also independent decision making power. The horizontal decentralisation is often corporatist in nature: associations of professional artists and cultural workers play an important role in the formulation and implementation of policies concerning artists, as well as in determining grants and project funding.

Vertical decentralisation revolves around the axis of the central government (the state) and the local self-government (municipalities).The state is financially and administratively responsible for the national art and cultural institutions, but it also promotes wider and more equal access to the arts and culture by providing either statutory or discretionary financing for regional and local cultural institutions. Previously, this work was supported by grants-in-aid that were specifically targeted by the Ministry of Education and Culture. In the early 1990s, these grants-in-aid were integrated in the overall system of statutory state transfers to municipalities. These automatic transfers, calculated on the basis of preset cost-compensation and equity criteria, now cover public libraries, institutions of adult education, non-institutional municipal cultural activities, basic arts education, museums, theatres and orchestras.

In the case of vertical decentralisation, the "third sector" also plays an important role. The role of professional cultural and art organisations as lobbyists was already indicated. Yet, the "third sector" has two other roles. Firstly, the voluntary organisations are important in enhancing cultural participation and amateur arts. Secondly, although dependant on public support the majority of cultural and art institutions (especially museums, theatres, but also some orchestras) are operated as non-public organisations (voluntary associations, foundations, non-profit joint stock companies).

The Finnish model has three further unique features, which are, however, at present under pressure to change. The first feature is the reliance on public ownership and public budgets and, especially, on legislation, which has been used to guarantee the stability (statutory status) of public funding for the arts and cultural services. The statutory status implies that the criteria used for funding can only be changed through an Act of legislation passed by Parliament.

The second feature has been the central role in the financing of the arts and culture from special earmarked funds, that is the profits from Veikkaus Ltd., the state owned lotto, football and games pools and sports betting company, which, alongside the arts and culture, are also used to finance sports, youth policies and science. As an aftermath of the economic recession of the early 1990s these funds, originally planned for discretional use only, were used regularly to finance statutory state subsidies e.g. public libraries, theatres, orchestras and museums. Consequently, there was less central government money for new projects and initiatives. The reliance of the central government funding on the profits of Veikkaus also increased and reached the highest level in 2001, about 70% of the funds allocated in the budget of the Ministry of Education and Culture to the arts and cultural services. The new Acts on Lotto, Football and Games Pools and Sports Betting and on the Use of Veikkaus Profits have started to increase the amount of tax-based appropriations and lowered the share of Veikkaus profits in the state financing of the arts and culture. In 2015 this share of the Ministry's funding of the arts and culture was 51%.

The third unique feature of the Finnish public sector administration has been the lack of autonomous regional level governance – in general or in the arts and culture. On the other hand, the Arts Council system was extended, at the very beginning, to the regional level by creating the system of eleven provincial arts councils. As the central government provincial office administration was reformed, the name of the councils was changed to that of regional arts councils and their number was raised to thirteen. In 2008 a regional arts councils' unit was established at the Arts Council of Finland in order to better co-ordinate the work of the regional councils with each other and also with the national arts councils. The overall governance of the regional arts councils was removed from the Ministry of the Interior to the Ministry of Education and Culture. This system of regional arts councils was preserved, when in 2013 the Arts Council of Finland became the Arts Promotion Centre Finland (see chapter 1.2.2).

Already in the old state subsidy system some of the art and cultural institutions financed jointly by the state and the municipalities received the status of regional institutions (regional historical and art museums, regional theatres) and were granted additional subsidies for their regional functions. Within the present financing system the Ministry of Education and Culture can furthermore designate some institutions as regionally significant and allocate them additional funding. These funding arrangements do not actually make the institutions really regional, with regard to their ownership and management, intellectual resources or programming. On the administrative level, the eighteen regional councils (that were originally associations of adjacent municipalities for physical planning) were reorganised for and invigorated by EU membership and have taken over a variety of regional planning and development functions, some even in the field of culture. Yet they are still associations of municipalities, not independent regional bodies and their role in enhancing cultural development in the regions is still rather marginal.

Cultural policy objectives

According to the Ministry of Education and Culture (www.minedu.fi/en), the objectives of cultural policy in Finland relate to creativity, cultural diversity and equity.

Thus, Finnish cultural policy aims:

- to provide favourable conditions for the work of artists, other creative workers and cultural and art institutions;

- to promote the preservation and development of cultural heritage and cultural environments;

- to enhance equal access to, accessibility of and diverse use of culture;

- to boost production, employment and entrepreneurship in the cultural sector;

- to reinforce the cultural foundation of society.

The affirmation of national identity was originally the main cornerstone of the Finnish cultural policy. Promotion of artistic creativity has been the second prime objective of Finnish cultural policy. This has traditionally been reflected in the endeavour of the state to take care of its artists and to improve their economic position through systems of state arts grants and pensions.

According to the Ministry, cultural policy is a significant factor in the implementation of welfare, regional and innovation policies. Following international examples, the Finnish government has, since early 2000s, started to emphasise creativity and innovation and their contribution to economic growth. The first planning effort in this area was the drafting of a national creativity strategy prepared by three task forces representing a wide spectre of civil servants from different ministries, universities and art schools, artists and representatives of the business sector in 2006. In 2007, the Ministry of Education and Culture started an extensive six year development programme for enhancing the growth and internationalisation of the Finnish creative industries and promoting entrepreneurship within the framework of the EU Structural Fund programmes for the years 2007-2013. During the programme period 2014-2020 cultural projects will be financed by the Sustainable growth and jobs 2014 – 2020 –programme. There is two national development actions are called Creative Skills and Inclusive Skills. The funding for the programmes is 11 million euros per action (for information on the current Social Fund programme, see also chapter 3.5.1 and chapter 7.2).

The shared responsibility of the state and the municipalities in providing, financing and maintaining a regionally comprehensive system of cultural services clearly shows an effort to expand participation in cultural life and access to culture. The adoption of the arm's length approach in art policies and in the use of expertise and the very fact that the municipalities have the prime role in providing these services are an indication of decentralisation – both horizontal and vertical.

Protection of minorities including the Swedish-speaking Finns, the Sami and the Roma can be seen as an aspiration for promoting cultural diversity. The decisions granting the immigrants and refugees basically the same social and economic rights as Finnish citizens reflect both equality policies and the will to increase cultural diversity. The more abstract principles, promotion of human rights and cultural rights, reflected in the new spirit of the Finnish Constitution and the ratification of all relevant international conventions and agreements can be seen as the moral basis of these more practical legal endeavours.

The above list of objectives correspond well to those used as the test criteria in the Council of Europe's review programme of national cultural policies. On the other hand, the ideas that the arts and culture should serve economic growth, increase exports and employment and function as a positive factor in regional and local development and social cohesion have become increasingly popular in Finland. The combining of the traditional objectives with these new economically oriented objectives were reflected in the 2015 strategy of the Ministry of Education and Culture where the following strategic "key functions" were listed:

- safeguarding equal access to education and culture;

- promoting intellectual growth and learning;

- enhancing opportunities for sharing and participation;

- providing resources for improving the cultural and economic competitive capacity of the Finnish society;

- opening up new channels in order to diversify the Finnish impact in the international community; and

- improving effectiveness in the cultural sector.

The latest 2020 strategy of the Ministry of Education and Culture focuses even more on the competitive edge of the Finnish economy and culture. The vision is to place Finland among the top countries in the world in intellectual competence, sharing and creativity by 2020. The Ministry must empower itself for this purpose and implement the following four programmes:

1. The power of cultural competence

- increase understanding and promotion of new contents and structures of cultural competences.

2. Competetive edge

- identify factors that shape Finland's competitive edge;

- using the Ministry's assets to guide the industrial and occupational transformations; and

- understand and guide education and culture as commercial activities.

3. Prospering regions and cultural and economic environments

- developing new governance and partnership models for enhancing regional vitality and controlling related risks; and

- introducing new service production models developing cultural and economic environments.

4. Sharing and sense of community

- identifying how a new sense of community is bound to shape the Ministry's activities and especially its governance functions, which pre-suppose strengthening the sense of institutional community;

- enhancing active participation of cultural and linguistic minorities; and

- establishing a project for hindering alienation.

The Ministry of Education and Culture Strategy for Cultural Policy will be updated in 2016, to be extended into year 2025. A draft version of the new strategy was published in autumn 2016 and the final strategy document will be published in 2017. The strategy will reflect on cultural policy from the viewpoint of uncertainty in the development of the economy, political power, in climate issues and human values; the polarisation of social life; increasing immigration and diversity as “the new normal”; and the role of ICT in economic and social development. Culture will be in the focus, but from a multidimensional point of view. See also chapter 2.1 Main cultural policy issues and priorities.

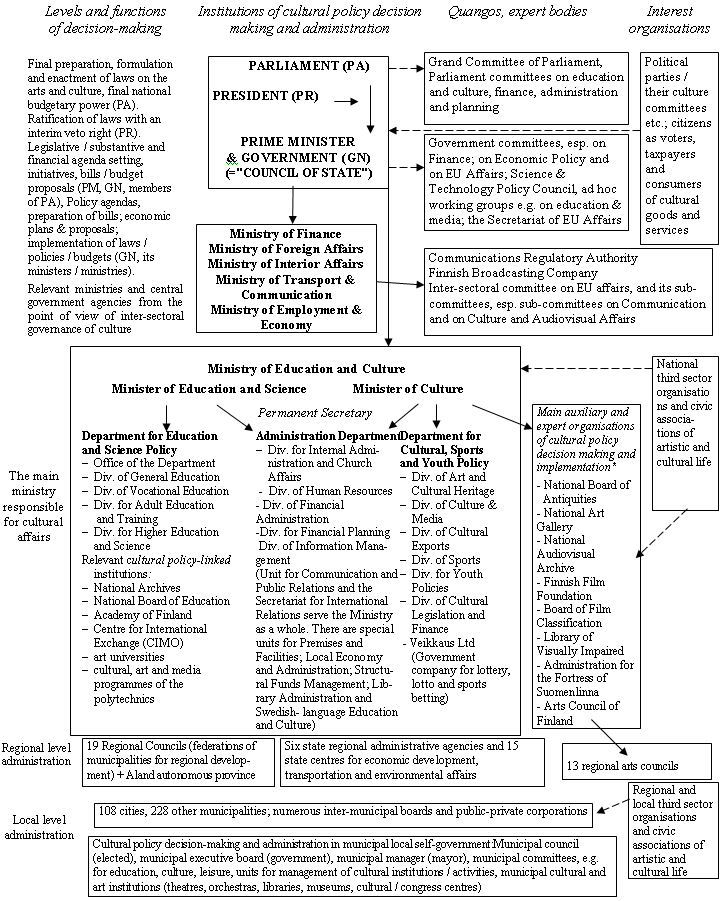

The following organigram gives a detailed overview of the Finnish national system of cultural policy decision-making and administration in its wider administrative, political and social setting. The core of the system is the Department of Culture and Sports and Youth policies of the Ministry of Education and Culture. The organigram also depicts in detail the other core of the Ministry, Department for Education and Science Policy, which is responsible for general and professional education in the arts and culture.

Like the overall Finnish political and administrative system, the Finnish cultural policy system is simultaneously highly decentralised and highly centralised. This is due to the fact that the local government system is strong and autonomous. On the other hand, with the advent of the social welfare state, the main burden of maintaining modern public services including cultural services, were shouldered by municipalities; while the state set the legislative frameworks and was legislatively committed to compensate a statutory share of expenditure. In the late 1980s and in the 1990s, this system, which had earlier covered public libraries and adult education, was expanded to include museums, theatres, orchestras and basic (extra-curricular) arts education. As a result of this development, the state is mainly responsible for the arts support systems, national cultural and art institutions, international cultural co-operation and university level cultural and arts education and shares with the municipalities the financial responsibility of maintaining the nation-wide system of performing arts institutions and cultural services.

Municipalities maintain infrastructure for local cultural and arts activities and they also receive central government subsidies for infrastructure investments. As to the cultural policy competence, the state and the municipal sector are formally on an equal footing although the state has a stronger hold of the steering wheel - that is legislation and financing. There is no overall autonomous regional administration, although EU-membership has strengthened the role of the regional councils, which are federations of municipalities.

In the cultural policy decision-making, the final legislative and budgetary powers rest with Parliament; the overall and co-ordinating executive powers of policy initiation, planning and implementation lie with the government (Council of State), and sector policy initiation, planning and implementation powers are the responsibility of the Ministry of Education and Culture. Municipalities, with their own elected and managerial political and administrative decision-making bodies (see the organigram) provide a counterbalance to these national powers.

In Parliament, the main work in preparation of bills and budget proposals is carried out in parliamentary committees. The Parliamentary Committee of Education and Culture deals with cultural policy issues but the powerful Committee of Finance checks and sets the financial frames for all budget allocations. After Finland's accession to the European Union, the Grand Committee became an increasingly important body that monitors the relations between national and Union legislation and policies. For that purpose it hears the ministers before and after the Union's Council meetings. This means that the ministers, among them the Minister of Education and Culture, have become responsible to Parliament in a new direct manner.

After its appointment, a new government is obliged by the Constitution to submit its action programme as a formal communication to Parliament for discussion. The programme sets the agenda for the government and it is accompanied by proposals of general and sector development programmes and projects. Culture, youth work and sports, which are considered a joint administrative sector, usually receive a rather short development plan in the programme. In recent years, the government's plans and programmes concerning the overall state support for the municipal sector and third sector institutions are more salient for the arts and culture than the proposed specific policy measures. Art and culture, and youth work and sports, although supported by the same types of state statutory transfer (subsidy) system as other public services, are, however, set apart from other services by their special source of financing. They are financed prominently from profits of the state lottery, football and games pools and the sports betting company (Veikkaus). These profits and their use do not follow the same pattern as the overall financial policy of the central government, because overall public finance fluctuations and gambling interests do not always coincide and, also, the state budget proposal for a given year is made before the actual annual amount of Veikkaus profits is known. Although there are strict legislative rules limiting the use of Veikkaus profits to the arts, youth work, sports and scientific research, the Ministry of Finance and the ruling government have often, irrespectively, tried and succeeded in using them as compensatory resources to fill other budget gaps (see also chapter 4.1.2 and chapter 7).

The government does not have any permanent committees or other expert bodies responsible for cultural policy purposes. It can though set up special working groups to monitor and prepare decisions in important policy sectors.

On the sector level, the main planning and executive responsibility lies with the Ministry of Education and Culture. In the Ministry, there are two ministers: the Minister of Education and Science and the Minister of Culture, Youth and Sports. The latter presides over the Department for Cultural, Sports and Youth Policy, which from the beginning of May 2014 was divided into two separate Departments: Department for Art and Culture and Department for Youth and Sport.

The Ministry and its departments and divisions focus on strategic planning and governance through information provision and performance contracts. In cultural policy implementation the following organisations are of prime importance:

- the system of arts councils and its specific art form councils, which is responsible for implementing arts and artists' policies and provides peer group evaluation mechanisms for deciding grants for artists and artist-led projects; as well as regional art councils. From 1 January 2013 a new government expert body, Arts Promotion Centre Finland, started its activities and replaced the former Arts Council of Finland (see below).

- the National Board of Antiquities which, besides its archaeological functions, is also the main governmental expert body for the whole heritage sector and professional museum activities; and

- the Finnish Film Foundation which allocates public support for film production and distribution.

Furthermore, more specific expert and national policy implementation functions are carried out by bodies such as the National Art Gallery, National Audiovisual Institute, Library for the Visually Impaired (CELIA), and the Administration of the Fortress of Suomenlinna (a UNESCO World Heritage Site).

The Arts Promotion Centre Finland

In 2010 the Ministry of Education and Culture prepared a draft law which proposed the dissolving of the present national Arts Council system and establishing in its place another organisation named "Arts Promotion Centre Finland" (Taiteen edistämiskeskus in Finnish, abbreviation Taike). The idea behind re-organising the system of arts councils was to increase the transparency of decision making and the flexibility of the art form councils in responding to the new art forms. In the end the most important issue was to separate the peer review expert body from the administrative function of the council as they had become increasingly intermingled. This separation was felt to be essential for strengthening and safeguarding the autonomy of the arts.

Instead of an expert body, the new organisation was to be of a central agency type with a centralised but light organisational structure a well-functioning and receptive information system. Understandably, this draft law caused a lot of commotion among professional organisations of artists and cultural workers and caused a lively debate in the press. After almost two years of debate the Parliament of Finland finally passed the bill establishing the new Arts Promotion Centre Finland in November 2012 and the centre started operating on 1 January 2013.

The official task of the Arts Promotion Centre Finland is to promote the arts and the work of artists on both national and international levels, as well as to promote those aspects of culture that are not covered by any other official agency. The Centre is an expert agency under the Ministry of Education and Culture. It comprises a Central Arts Council (Taideneuvosto in Finnish), national arts councils, regional arts councils and separate boards. In charge of the overall management and development of the Centre is a director, appointed for a fixed five year term. The current director is Ms Minna Sirnö, formerly a member of Parliament and a vice-chairperson for the Left Alliance party.

Highest in the hierarchy of the expert bodies is the Central Arts Council which is appointed by the Ministry of Education and Culture for a three-year term. The Council makes decisions regarding the number, names and roles of the national arts councils. It also appoints the members of both national and regional arts councils for two-year terms based on expert recommendations. The Central Arts Council serves as an advisory body to the Ministry of Education and Culture in policymaking regarding the arts. The Central Arts Council is a new type of body in the history of Finnish arts policy and its mandate is so wide and somewhat ambiguous that it remains to be seen what direction it will take.

There are 13 regional arts councils (their number has stayed unchanged) and for the term 2015-2016 there are seven (compared to ten in 2013-2014) national arts councils: Architecture, design and environmental art; Audiovisual art; Performing arts; Literature; Music; Visual arts; and Interdisciplinary art, diversity and international activities. In addition there are two separate boards, one for grants and subsidies to writers and translators and one for public display grants to visual artists. The councils decide on the awarding of grants and awards to artists on the basis of peer reviews. The national arts councils have up to four sub-commitees for the preparation of peer reviews.

According to the Strategy of the Arts Promotion Centre (Taike) for 2015-2020, Taike promotes:

- the livelihood and working conditions of artists and therefore the availability and accessibility of the arts;

- the internationalisation of the arts;

- the diversity of the arts and intercultural dialogue; and

- the status and visibility of the arts in society and the rights of citizens to art and culture.

In the strategy Taike states as its core values expertise, openness and respect in relation to its customers and art community, the agency itself and its empolyees and the larger society of citizens and public administration.

As operational objectives the Centre states that by 2020:

- Taike has established its position as an expert in art and artist policies;

- Taike has created an electronic service package based on the needs of its customers and peer reviewers that is of the highest quality in terms of usability; and

- Taike has reorganised its structure and operating methods to correspond better with the tasks assigned to it. Taike has clarified its division of duties with other public administration bodies.

As its arts promotion objectives Taike states high quality art and established cross-sector activities among artists and cooperation that promotes livelihoods. According to objectives by 2020:

- Taike has developed its direct artist grants to respond to the needs of professional artists and communities of free artists; and

- Taike evaluates the implementation of its strategic targets annually in connection with its annual report and if necessary reviews its targets on the basis of this evaluation.

It is still early to comprehensively evaluate what role the Centre will take in the field of arts and culture. An evaluation of the legislative changes is under way (to be completed in autumn 2016) and will provide a starting point. It is clear that the Centre will be a significant financing body in Finland and most likely the Ministry of Education and Culture will continue in delegating operational duties to the Centre.

International cultural co-operation is managed for the whole ministry by the Secretariat of International Relations. The Department for Cultural, Sports and Youth Policy does not have any units or special plans for intercultural dialogue, partly because the national legislation and administration focuses primarily on the economic and social conditions of minority groups, partly because all educational policies, including education in the arts and culture, come under the jurisdiction of the Ministry's Department of Education and Science (see below and chapter 1.2.6).

The following other ministries have an important say in the formation and implementation of cultural policies:

- the Ministry of Finance has a guiding and controlling role in respect to economic planning and budget processes of all ministries;

- the Ministry of Employment and the Economy provides support for R&D in general and more specifically for the ICT and media and culture / creative industries;

- the Ministry of Transport and Communications has an important planning and implementation role in telecommunications and radio and television activities;

- the Ministry of the Interior is responsible for regional development and has a central role in organising and co-ordinating regional development programmes and related EU-initiated financing; and

- the Ministry of the Interior and its Directorate of Immigration selects and shapes the immigrants through multistage processes consisting of the management of entry and preliminary hearings, application and provision of residence permits and as potential ending of the naturalisation process).

The Non-discrimination Ombudsman (before 2015, the Ombudsman for Minorities) and several advisory bodies have a central role in the protection of minorities, in anti-discrimination policies and in the integration of refugees and immigrants. Until 2008 they, and the integration policy implementation, have been located at the Ministry of Labour. However, the Ministry of Labour was merged by the new government with the Ministry of Trade and Industry (to form the Ministry of Employment and the Economy) and most immigrant policy administration was relocated within the Ministry of the Interior. The labour market and employment issues of immigration policies were transferred to the new Ministry of Employment and the Economy. As for other minority issues, Roma affairs are administered by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Ministry of Justice monitors the observing of the Sami autonomy legislation and administration. The municipalities have the right of taxation, that is, the right to determine the rate of municipal income tax for individuals and enterprises. The state (central government) addresses inequalities and problems of infrastructure development in public services through financial transfers, at present mainly through the statutory subsidy system. This very system is also used for transferring most central government financial support for maintaining more equal regional and local supply of art production and culture services (for the functioning of the system in the performing arts and other cultural services, see chapter 1.1).

Cultural policy decision-making at the municipal level is in the hands of the Municipal Council (elected assembly), the Executive Board (reflecting the party divisions and coalitions in the Council), sector municipal committees and the executive staff, headed by the municipal manager / mayor. Regarding the sector committees and administration, the trend in the 1980s was to integrate all cultural matters (theatre, music, amateur arts, etc.) under one municipal committee for culture. In the 1990s the trend was reversed and cultural matters have been increasingly distributed to trans-sector committees with broader responsibilities (e.g. committees on leisure, tourism, etc.).

There is no autonomous regional administration with elected decision-making bodies. The regional administration of the state has been recently re-organised (2010) and went through a radical reform. The regional administration consists of six regional administrative agencies (former 11 provincial units) and fifteen centres for economic development, transportation and environmental affairs. At the same time, eighteen regional councils (federations of municipalities) have gained a greater role in regional development and planning. This is partly due to their responsibilities in planning and monitoring programmes financed within the framework of the EU programmes. This development has been counter-balanced by the organising of the regional state administration as regional development centres for such important sectors as the economy and employment, forestry, transportation and the environment.

The Regional Art Councils are an extension of the system of the national arts councils to the regional level. Basically, the arts councils have the same functions at regional level (grants and other support to artistic work, project grants) as the Arts Promotion Centre Finland and its art form councils have nationally.

The basic architecture of the core cultural policy decision-making and administration, as it is depicted in the organigram (see chapter 1.2.1), has not changed much during the last fifteen years. The various sections of the Department of Cultural, Sports and Youth Policy have been altered and names changed. Some delegation of decision-making from the Department to the quangos, especially to the system of arts councils, has also taken place. The regional arts councils, which were directly responsible to the Ministry, were made an administrative part of the "national" system of Arts Councils. On the other hand, crucial changes in jurisdiction and decision-making powers have happened in such culturally salient fields as state-municipality relations, guidance and control of the media and the culture industries, and the administration of refugee and immigrant policies.

Please find the available information on this subject in 1.2.2.

Please find the available information on this subject in 1.2.2.

Last update: March, 2017

Finland has been sometimes called a promised land of voluntary associations and citizen's civic action, in reference to the fact that there are 70 000 registered and operative associations which have about 15 million individual members, or three times the population. About 75% of the population is a member of one association, about 30% belong to one association and 8% belong to more than five associations. The present annual aggregate turnover of the associations and related civic actions has been estimated to be five billion EUR, with public support of 1.6 billion EUR. The associations offer employment to 82 000 employees; of these 25 000 are part-time. Yet the share of the employees of the associations of the total gainfully employed population is 3.5% – the same per cent as the value added contribution of the association sector to GDP. All these figures do not reflect the voluntary section only; the aggregate figure includes the contributions of some religious organisations, trade unions, and other "third sector" organisations such as foundations, small co-operatives, political parties and adult education.

In addition to employed staff, the voluntary associations rely strongly on voluntary work. It has been estimated that the association sector's annual aggregate labour time is more than 123 million hours, which corresponds to an annual labour contribution of 80 000 fully employed persons.

In comparison with these aggregate figures we have less exact statistics on the size and economic contributions of voluntary associations and civic action in the arts and cultural sector. It has been estimated that the share of cultural associations of the total 70 000 associations is about 20% or 14 000 associations. On the other hand, it has been proposed that there are two and a half thousand art / artists' associations, seven hundred heritage and museum associations and about a thousand associations for the promotion of the arts and culture. What seems to be true is that these are the largest categories in this order; and that music associations are the largest group amongst the art / artists' associations. Amateur music associations feature strongly among music associations.

In order to have a picture of the relative importance of the association sector for the arts and culture, we can avail of a piece of information presented in a recent policy report of the Ministry of Education and Culture. The report outlined the basic principles and objectives of the Ministry's Strategy for Civil Society organisations 2010-2020 as part of the governments Civil Society Programme. The following Table was presented in the Ministry's report. http://www.minedu.fi/export/sites/default/OPM/Julkaisut/2010/liitteet/opm16.pdf?lang=

Table 33: National registered associations which received subsidy in 2008 from the Ministry of Education and Culture

| Category of association | Number of organisations | Basic subsidy | Special subsidy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sports organisation (a) | 131 | 35 900 000 | 5 080 700 |

| Youth / youth policy organisation | 118 | 13 124 300 | 2 177 000 |

| Association managing a study centre | 11 | 3 000 000 | 150 000 |

| Research communities (sector research of sports / culture ) | 31 | 6 190 640 | 2 339 214 |

| Friendship society | 37 | 2 622 000 | |

| Arts / artists association | 111 | 5 310 200 | 2 107 955 |

| Peace association | 9 | 396 600 | |

| Association enhancing multiculturalism, against racism | 43 | 273 400 | 13 000 |

| Counselling association | 5 | 5 139 000 | |

| Women's organisation | 2 | 293 000 | |

| Other | 3 | 146 000 | |

| Total | 501 | 72 395 340 | 11 866 969 |

Source: The Strategy of the Ministry of Education and Culture for Civil Society Organisations, publications of the Ministry of Education and Culture 18/2010.

In the Finnish political system, the plenary sessions of the government (Council of State) and its standing committees and working groups have a strong role in controlling and guiding individual ministries and in co-ordinating their work. Inter-sectoral co-ordination has been perceived as an important issue, but few institutional mechanisms to maintain it have been introduced.

Finnish EU-membership has also brought forth a need for inter-ministerial co-ordination. There is a special Committee of Ministers for the co-ordination of EU-affairs and, on the top civil servant level, an Inter-Ministerial Committee of EU-Affairs, with a number of sector specific preparative sub-committees, among them a sub-committee for culture and audio-visual affairs (often called simply the sub-committee 31).

In any case, the co-ordination of cultural policy planning and decision-making rests with the Ministry of Education and Culture, but important roles are also played by: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the co-ordination of "cultural diplomacy"), the Ministry of Transport and Communications (concerning co-ordination of media, communications and information technologies), the Ministry of Justice (preparing freedom of expression legislation, court processes in immaterial rights issues) and the Ministry of the Interior (immigrant issues). From the cultural policy point of view, the Ministry of Employment and Economy has had a central role in respect to R&D, SMEs and competition issues in the media and culture industries. As the Ministry of Labour was merged (from 1 January 2008) with the Ministry of Trade and Industry and renamed the Ministry of Employment and the Economy, this new "super-ministry" has had a strong say not only in R&D, SMEs and competition issues but such culturally salient policy domains as public works, construction projects, employment policies (including relations with the ILO), creative industries http://www.tem.fi/index.phtml?l=en&s=272 and gender issues. In the same overall administrative reform, the regional development issues were transferred from the Ministry of the Interior to this "super-ministry", and the financial monitoring and planning power of the other "super-ministry", the Ministry of Finance, was expanded by including in its jurisdiction, economic, administrative and information technology issues concerning municipal and regional governance.

So far these administrative reforms have not altered the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and Culture. Directly, they caused a conflict only in one cultural policy domain. The administration of copyright policies has traditionally belonged in the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and Culture and it was proposed that they should also be transferred to the new "super-ministry", which already was responsible for industrial rights. As the copyright stakeholders, especially artists' organisations, protested against this transfer, the copyright issues remained within the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and Culture (see chapter 2.1 and chapter 4.1.6).

There are no inter-governmental bodies in cultural policy-decision making and administration. As to public cultural services, the Association of the Finnish Local and Regional Authorities is an important intermediary between the central government, the regions and the municipalities. To a certain extent the regional arts councils also function as intermediaries between the central government and regions. The financing from the EU Structural Funds has created a whole host of new planning and supervisory organisations, which also co-ordinate regional cultural policies to a certain extent.

The three previous governments have wished to enhance inter-sectorality in state policy-making and administration. The Centre-Socialist (2003-2007) and Centre-Conservative-Green (2007-2011) governments introduced in their action plans the idea of programme-based management and outlined several inter-sectoral policy programmes for employment, entrepreneurship, the information society, civil society, health promotion and the wellbeing of children, youth and families, but did not propose any specific instruments for coordinating their implementation. Culture was not explicitly included in any of these programmes. The Conservative-Socialist-Green government (2011-2015) outlined three inter-governmental strategic priority areas of which the priority area of economic growth, employment and competitiveness, managed by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy, was the most central for cultural policy. The priority areas were made up of several action points with responsible ministers, with the Ministry of Education and Culture

The current Centre-Conservative-Populist (2015-2019, Prime Minister Juha Sipilä) government has a new approach of so called key projects

The government strategic programme states in its vision of 2025:

“Finland is open and international, rich in languages and cultures. Finland’s competitiveness in built on high expertise, sustainable development and open-minded innovations based on experimentation and digitalisation. We encourage renewal, creativity and interest in new ideas. Failure is acceptable and we learn from our mistakes.”

The Government Programme is an action plan devised by the political parties represented in the Government. Programme’s implementation plan focuses on the schedule, measures and financing of the key projects and the most important structural reforms.

The Programme has five strategic objectives, which include a total of 26 key projects. Six of the key projects are within the administrative branch of the Ministry of Education and Culture, under knowledge and education.

Key projects:

- New learning environments and digital materials to comprehensive schools

- Reform of vocational upper secondary education

- Acceleration of transition to working life

- Access to art and culture will be facilitated

- Cooperation between higher education institutions and business life will be strengthened to bring innovations to the market

- Youth guarantee towards community guarantee

As regards cultural policy, the main government priority deals with facilitating access to art and culture. The programme states that:

- Children and young people will be supported in becoming more active.

- Basic education in the arts and cultural activities will be increased.

- Access to basic art education and children’s culture, which is currently not available to all in every part of the country, will be improved.

- Greater recognition will be given to the wellbeing aspects of culture.

- Art exhibitions in public spaces and institutions will be promoted to bring culture closer to every Finnish citizen.

- The principle of investing up to 1% of the construction costs of public buildings in the acquisition of artwork will be expanded in cooperation with the social welfare and health care sector in order to support the welfare impacts of the art

All in all 10 million EUR are allocated for these measures for 2016-2018. The sum for 2016 is 2,6 million EUR.

Government Programme: http://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/sipila/government-programme

For more information on the main projects, see chapter 2.1 (Current issues in cultural policy development and debate).

In 2003-2004, a planning process was carried out to draft a policy strategy for the promotion of export of Finnish cultural goods and services. This planning work was co-ordinated by the Ministry of Education and Culture, but the Ministry of Trade and Industry (since 2008 the Ministry of Employment and the Economy) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs participated on an equal footing and participants and experts came from different administrative sectors and walks of life. The final report "Staying power of Finnish cultural exports!" was published in 2004, and the Ministry of Education and Culture initiated its implementation by establishing in 2005 a special Division of Cultural Exports (since then it has been ). In 2010 this division was transferred into the Arts Division as a special focus area. It has been estimated that some EUR 228 million was invested in the Cultural Export Promotion Programme during the period of 2007-2011. In the 2013 budget, EUR 9 000 000 was allocated for the implementation of the Ministry's cultural exports and international co-operation activities.

The minority, ethnic, refugee and immigration affairs are concentrated in two ministries, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Employment and the Economy (see this chapter, third paragraph). There is a sectoral division in these issues also within the Ministry of Education and Culture. The Department of Cultural, Sports and Youth Policy defines its objectives e.g. in the Immigration Policy Outlines, in rather general terms, as "… the cultural needs of minorities will be enhanced by increasing the grants to correspond to the escalation of immigration; and these needs will be taken better into account in the decisions and activities of the main cultural policy support systems and cultural and art institutions". In the preamble of the 2007 State Budget, the Department promised to enhance equal access and conditions for equal participation especially in respect to ethnic groups and disabled people. In addition to the "traditional" concern of bilingualism and the status of the Sami (see chapter 2.5.4), the policy actions so far have been limited to the distribution of grants (EUR 650 000 in 2011) to immigrant and minority organisations and artists and to projects and programmes carrying out anti-discrimination campaigns. Since 2009, the Arts Council of Finland (presently the Arts Promotion Centre Finland) has awarded grants to arts projects promoting multiculturalism (immigrant artists) with a budget of EUR 97 000 in 2014.

The other core department of the Ministry, the Department of Education and Science, has had closer links to other ministries, especially to the Ministry of Labour, in promoting equal opportunities for minorities, ethnic groups and immigrants. As the Ministry of Labour has been merged with the Ministry of Trade and Industry, to form the Ministry of Employment and the Economy, it is difficult to say what will happen to these links in the near future. As to the education policies of the immigrants and minorities, the main responsibility for the research and development activities, experiments and planning of courses and educational material lies with the Ministry of Education's main educational expert body, the National Board of Education. Yet, the focus of educational policy efforts has not been longer term promotion of multiculturalism but the opening up opportunities for immigrants and refugees to become integrated into the Finnish educational system and subsequently also into Finnish labour markets. The native tongue of immigrants is seen as important in the initial integration stage and municipalities can provide teaching in native languages if they so wish and have resources for this purpose.

Yet, educational policies provide the closest link of the Ministry of Education and Culture to the overall national system of policy-making and administration in the minority, ethnicity and immigration issues. In this system, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs shapes these issues from the point of view of national security and the Ministry of Interior, through its border guards, police authorities, Department of Immigration and the Directorate of Immigration, has the first say in entry / asylum issues, residence permits and naturalisation. After the overall re-organisation of the Finnish ministries, most other refugee and anti-discrimination issues are located within the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior.

Two important legal instruments, the Non-discrimination Ombudsman and the National Discrimination Tribunal are also located in the Ministry of the Interior. These organisations are, however, independent of the Ministry in their decision-making processes. The former is the main authority in issues concerning the legal protection and the promotion of the status of ethnic minorities and foreigners and in maintaining equality and non-discrimination practices in ethnic relations. The activities of the latter are defined in the Equality Act i.e. preventing and combating ethnic discrimination in working life and service provisions. The Board of Ethnic Relations, which plans and co-ordinates activity in all issues concerning refugees, migrants and ethnic relations, is also located in the Ministry of the Interior. This Board and the National Discrimination Tribunal have a representation of immigrant groups and traditional national minorities among their members. No doubt these three organisations also co-ordinate the activities of different ministries, but their main purpose is to operate as bodies where experts and different stakeholders seek solutions for practical social, economic and human rights problems. Consequently, municipal administration and voluntary associations have shouldered the responsibilities for the immigrants and minorities in the fields of arts and culture – and also in respect to multiculturalism and intercultural dialogue. For their role, see chapter 2.6 and chapter 2.5.1 for cases illustrating Finnish approaches to intercultural dialogue.

Last update: March, 2017

The division of financial responsibilities between the two main financiers, that is the state and the municipalities, is clear. The state takes care of the national cultural institutions, including university level arts education; and it supports also the culture industries, mainly cinema. With the financial transfers through its statutory system of subsidies the state also levels disparities throughout the country in the provision of performing arts (theatres, orchestras) and library and museum services; and the regional arts councils mitigate inequalities in the national spread and support for the creative arts. The state subsidy systems help to maintain an extensive system of extracurricular art education and professional education for cultural occupations. The state also bears the main responsibility for the central national infrastructure: construction and renovation of nationally significant buildings, maintenance of the main information and communication systems; and it also subsidises construction and communication costs of the national networks of cultural service institutions.

Municipalities, in collaboration with third sector organisations, maintain the basic cultural service systems and their infrastructure. Minimum services can be found in small rural municipalities where they consist of public libraries, adult education units and support for some socio-cultural events and activities; the maximum service system can be found in the Helsinki Metropolitan Region, consisting of the City of Helsinki and three other municipalities: Espoo, Vantaa and Kauniainen. Between these two extremes, other cities can be divided into three categories: major cities, regional centres and small towns. In this classification, the presence / absence of a university and other institutions of higher education and culture make a clear difference. These institutions guarantee interested and committed audiences for the arts and culture. Economically the worst off are the regional (province centres) that must maintain reasonably extensive provision of arts and cultural services but have small and fragmented audiences and pay relatively higher costs for maintaining this provision. There are some indications that the institutions – public libraries, historical and art museums – which have been assigned with a special regional role and given additional state subsidies, have problems in fulfilling this role effectively.

In more general terms, it has been argued that the state has, since the 1991-1993 recession, retracted from active support and levelling policies and forced the municipalities to carry a heavier financial burden. The municipalities in turn have expected the cultural institutions to increase their own earned income, especially box office earnings. However the most recent reform of the statutory system of central government subsidies has substantially improved the situation. In this reform, the state compensated for the cost deficit it had allowed to emerge in the statutory transfers during 1997-2005 by not reacting to the increase in the volume and staff costs. In the three years from 2008-2010 the statutory state subsidies to professional theatres, orchestras and museums in the statutory system increased by nearly 50 million EUR, almost by 80% compared to 2007, and in 2010 was 113.6 million EUR.

The impact and organisational level effectiveness of the increase were evaluated at Cupore (Foundation for Cultural Policy Research). According to the evaluation, the state funding increase made possible a considerable increase in the personnel of arts and cultural institutions, 427 person years altogether (8%). Also, the average yearly salary rose 8%. Hence, personnel costs increased substantially, 29.8 million EUR (16%). The rest of the increase was used for rents (12 million EUR) and other un-itemised expenses (7.9 million EUR).

The funding structure of the institutions changed. The relative share of total government funding increased from 23% in 2007 to 34% in 2010, and the relative share of municipal subsidies shrank from 49% in 2007 to 42% in 2010. In 57 out of 97 public institutions, the municipal support decreased.

The management of the institutions emphasised strongly artistic quality and the quality of content, staging, and exhibition layouts, audience education and museum pedagogy as the targets of the increased funding. From 2007 to 2010, the number of productions (theatre performances, concerts, exhibitions) increased by around 400 (3%). The number of attendances decreased by around 191 000 (-3%). Only orchestras were able to increase the number of productions (14 and 36% respectively) and private orchestras were also able to increase attendances (23%).

In order to understand the nature and functioning of the Finnish cultural and art institutions, we must return to the legislation.

Table 18: Current legislation pertaining to cultural and art institutions in Finland

|

CULTURAL POLICY LEGISLATION ON INSTITUTIONS COMMENTS | |

|---|---|

| FINANCING CULTURAL AND ART INSTITUTIONS AND CULTURAL SERVICES | |

| Act on Financing Education and Culture (previously 635/1998, now 1705/2009), pertaining to the provision of "non-basic" public services financed jointly by the state and municipalities | Specific "Financing Law"defining the rules for calculating and allocating central government transfers (subsidies) to municipal and non-profit local service organisations including professional local and regional theatres, museums, and orchestras |

| Act on Central Government Transfers to Municipal Basic Services (1704/2009), renews the transfer legislation, which aggregates most important ("basic") transfer systems and relocates them to be administered as one single package in the Ministry of Finance | General financing law defining the relative share of the state and municipalities in producing basic public services and provides the basic rules for calculating and allocating the transfer of state subsidies to municipalities |

| Lottery Act (1047/2001) | The revision of old legislation; gives the government the right to contract a monopoly for 1) lottery / lotto, football pools and betting, 2) slot-machines and casinos, and 3) harness race betting; orders the return of the profits to the state budget and earmarks their use for specific purposes |

| Act Regulating the Use of the Profits of Lottery / Lotto, Football Pools and Betting (1054/2001) | Defines the share of the annual returns of lottery / lotto, football pools and betting as follows: 25% to sports, 5% to youth policy measures, 17.5% for scientific research and 35% to the arts |

| Government Decree on Organising Lotteries (1345/2001) | Specifies the technical rules for all forms of lotteries |

| PROFESSIONAL CULTURAL AND ART INSTITUTIONS AND MUNICIPAL CULTURAL SERVICES | |

| Act on National Board of Antiquities (282/2004, original 31/1972, amended 1016/1987, 1080/2001) | Confirmed the legislative basis for the main expert and policy implementing body on heritage |

| Decree on National Board of Antiquities (407/2004) | Specified the Act on the Board of antiquities e.g. in respect of the status of the National Museum |

| Act on Finnish National Gallery (566/2000, amended 504/2004, previous Act 185/1990) | Provides an umbrella organisation for three state-owned art museums (those of domestic, foreign and contemporary art). This act is currently being amended and will come into effect on 1 January 2014 as the FNG will start operating as a foundation. |

| Act on National Audiovisual Archive 1434/2007 expands the tasks of the earlier Finnish Film Archive by including radio and television programmes in the archival material. | Organises the national administration of archiving films, television and radio programmes |

| Act on the Library for the Visually Impaired (11/78, 638/1996, amended 835/1998) | Provides national book services for the visually impaired |

| Act on Audiovisual Programmes (710/2011) and the Act on the Finnish Centre for Media Education and Audiovisual Programmes (711/2011). | These acts repeal the former acts on age classification of programmes for the protection of children against exhibition of pornography and violence and establish a centre for media education and audiovisual media which started to operate in 2012. |

| Act for Promotion of Film Art (28/2000) | Provides legal basis for the activities of the Finnish Film Foundation (founded in 1969 to support national film production and film art). |

| Municipal Cultural Activities Act (728/1992, amended 1681/1992) | Legislative basis for central government support to non-institutional cultural activities in municipalities |

| Museums Act (729/1992, amended 1959/1995, 1166/1996, 1072/2005) | Legislative basis defining professional museums eligible for central government subsidies according to the "Financing Law" |

| Theatres and Orchestras Act (730/1992, amended 1277/1994, 1460/1995, 642/1998, 1075/2005)) | Legislative basis defining professional theatres and orchestras eligible for central government subsidies according to the "Financing Law" |

| (Public) Library Act (904/1998), is specified by Decree 1078/1998 defining the tasks of the central Library and regional libraries in the public library system | Legislative basis defining the tasks of public (municipal) libraries eligible for central government subsidies according to the "Act on general government transfers to municipalities" |

| ADULT EDUCATION | |

| Act on Professional Adult Education (631/1998) | A new integrating law that professionalises the traditional forms of voluntary adult education and lays the ground for their public support |

| Decree on Professional Adult Education (812/1998) | Specifies the previous Act |

| ARTS EDUCATION AND TRAINING OF THE ARTISTS & PROFESSIONALS OF CULTURAL SECTOR | |

| Universities Act (558/2009), this new Act is a kind of desetatisation law dividing existing universities in two modes of management, either as public corporations or foundation-based institutions. | Defines the units, structure, functioning and financing and management the two types of universities |

| Act on Basic Education in the Arts (originally 424/1992, now 633/1998, amended 518/2000) | Integrates the organisation of extracurricular art education for children and youth and lays basis for its public financing |

| Decree on Basic Education in the Arts (255/1995) | Specifies the previous law |

| Vocational Education Act (630/1998) | Legislative basis for lower vocational education, including culture (handicraft, design, audiovisual media, visual expression, dance and music |

| Polytechnics Act (351/2003 and Decree (351/2003) | Defines the objectives and organisation of polytechnic education, including higher professional / vocational education in the arts, culture, media and humanities. New legislation for polytechnics is being developed on a government proposal from 2012, in operation from 1 January 2014. |

| Act on Pilot Programme on Postgraduate Studies in Polytechnic Institutions (645/2001). The Act was enforced up to 31.7.2005 | A further step to remodel polytechnics degree structure to that of universities |

Source: databank FINLEX http://www.finlex.fi/en/

The category of financing cultural and art institutions and cultural services illustrates the vertical decentralisation and organisation of joint financing for the arts and culture - especially cultural institutions and services - by the central government and local governments (municipalities). The first law in the list, the Financing Law, provides the formulas that are used to assess the share of the municipalities and central government in the financing of different institutional sectors (public libraries, professionally managed museums, professional theatres and orchestras and the organisations providing extra-curricular art education). The next law only indicates how close the relationship between the central government and local self-government (municipalities) are financially: the former provides financial transfers for the latter and gives them equal opportunities in the overall provision of public services.

The category of cultural and art institutions demonstrates the legislative basis for the cultural institutions. These laws and decrees actually specify the types of professional institutions that can be included in the sphere of a Financing Law made up of joint central government-municipal financing. Some of the national institutions like the National Opera and the National Theatre are private organisations, a foundation and a joint stock company, respectively. They are financed on an annual contractual basis and do not have special laws like the National Art Gallery (see Table 18, second section). There is no law either for the Radio Symphony Orchestra, which is operated within the Finnish Broadcasting Company (YLE), or for the National Museum (which is still a department of the National Board of Antiquities).

The institutions of professional education and training are administratively separated from the rest of the cultural administration, because they are within the jurisdiction of the Department of Education and Science of the Ministry of Education and Culture (see chapter 1.2.1). These educational institutions form a hierarchical line from the second level vocational education via polytechnics (N=29, with most having special programmes for the arts, arts management, media and humanities) to the art universities (N=4). This line includes also the earlier extensive system of music schools and conservatories and, at the lowest level, it is supported by the system of extra-curricular "general" arts education and the specialised secondary schools of art.

Further important institutions can be found in the category of adult education. The different forms of adult education (civic colleges, municipal study circles, adult education centres), which all had earlier separate legislative bases, have now been integrated within one umbrella Act.

It is difficult to pin down any general trends of development within this diverse institutional sector. There is a trend that is closely connected with the on-going processes of desetatisation and the adoption of some doctrines of New Public Management. These processes and doctrines appear for example as a system of performance contracts and the introduction of net budgeting and business accounting systems in central government and municipal accounting. There are also parallel demands that cultural and art institutions must earn more income as a ratio to their total expenditure. Recently in the public budgeting and account system the need to monitor and report the efficiency and longer term impacts of publicly financed activities have been emphasised. There are no definite earned income ratio criteria; however the City of Helsinki's officials have indicated informally that the city finds it difficult to finance institutions where their earned income is less than 20% of the total expenditure. Also, as mentioned before (see chapter 2.9), the current trend for organisation of cultural activities in Finland is to favour the foundation form of governance. The Finnish National Gallery will start functioning as a foundation from 1 January 2014, as will the Ministry's current subordinate Institute for Russia and Eastern Europe from 1 January 2013. The argument is that as a foundation, these organisations will be more agile and independent in organising and developing services and in diversifying sources of financing.

Last update: March, 2017

The information filled in Table 19 pertains only to professionally managed public or statutory state-subsidised institutions. For relevant statistics, see chapter 3.1, chapter 7.1, chapter 7.2.2 and chapter 6.2. The issue analyses in chapter 2.4 and chapter 2.9 illustrate the cultural policy role of the national institutions.

Table 19: Cultural institutions financed by public authorities, by domain

| Domain | Cultural institutions (subdomains) | Number (2010) | Trend (++ to --) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage sites (recognised) | 28 000 | ++ |

| Museums (site organisations) | 330 | + | |

| Archives (of public authorities) | n.a | - | |

| Visual arts | Public art galleries / exhibition halls | 63 (2007) | +- |

| Art academies (or universities) | 2 | +- | |

| Performing arts | Symphony orchestras | 29 (2012) | + |

| Music schools | 104 (2007) | +- | |

|

Music / theatre academies (or universities) | 2 | +- | |

| Drama theatres, main | 47 (2012) | - | |

| Music theatres, opera houses | 1 (2012) | +- | |

| Dance and ballet companies | 10 | - | |

| Books and Libraries | Libraries | 827 (2012) | -- |

| Audiovisual | Broadcasting organisations | 1 (2012) | +- |

| Interdisciplinary | Socio-cultural centres / cultural houses | n.a. | + |

| Other (please explain) | n.a. | n.a. |

Source: Statistics Finland, Cultural Statistics 2011and 2013, Finnish Mass Media 2011

Last update: March, 2017

Many of the institutions financed by the state and the municipalities are, in their legal form, private companies, foundations or associations and thus we could also speak of private-public partnerships. Even in these cases, funding based on their own earnings (sales of tickets etc.) is rather limited. The ratio of earned income varies between 10% (Radio Symphony Orchestra) and 55% (some private museums). Due to the high level of public subsidies, most of these institutions should be classified as "public", at least according to the criteria defined by the System of National Accounts. Multiple partnerships can be found in capital investments, especially in the construction of buildings. As a case in point we can use the Sibelius-House in Lahti, a city close to Helsinki. The main financiers of the concert hall were the City of Lahti and the state, but the role of the private investors, the wood industry enterprises, was also significant. Wood was used predominantly as the construction material and the firms wanted to open up new areas for the use of Finnish wood. The City of Lahti owns the building, but it is operated as a joint stock company. Similar partnerships have emerged also in the context of EU programmes, financed from the Structural Funds, for example the Sami museum in Lapland and a couple of regional cultural centres.

In order to understand the rather limited number and type of partnerships in financing and organising cultural and artistic activities, we must also have a brief look at private financing.