1. Cultural policy system

Ireland

Last update: November, 2020

Objectives

The main objectives of cultural policies implemented by different levels of the Irish public administration relate to the protection, development and presentation of heritage, culture, Irish language and the arts. There is an emphasis on the promotion of access to culture for all citizens of Ireland. More recently, government strategy documents have emphasised the role of culture in the development of the wellbeing of citizens. The cultural policy in Ireland is strongly in line with main European cultural policy principles of support of creativity, participation in cultural life and cultural rights and broadly in line with cultural rights policies.

Recently, in 2015, the Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht promised to deliver a new national cultural policy that would replace the Arts Act. The policy process offered an opportunity to review, adapt and renew the existing cultural policy legislation under one overarching cultural policy. While no such one-for-all policy came, a draft policy framework document was created with some new strategic objectives. For example, an all-of-government strategic approach has been attempted in the strategic vision. This has had some success in the area of arts education, but without any legislative changes underpinning such inter departmental cooperation it remains an elusive and vague objective. The other main strategic objective is a focus on culture as a means of increasing wellbeing. This objective has been supported by the establishment of a new Creative Ireland agency within the culture department.

Main features

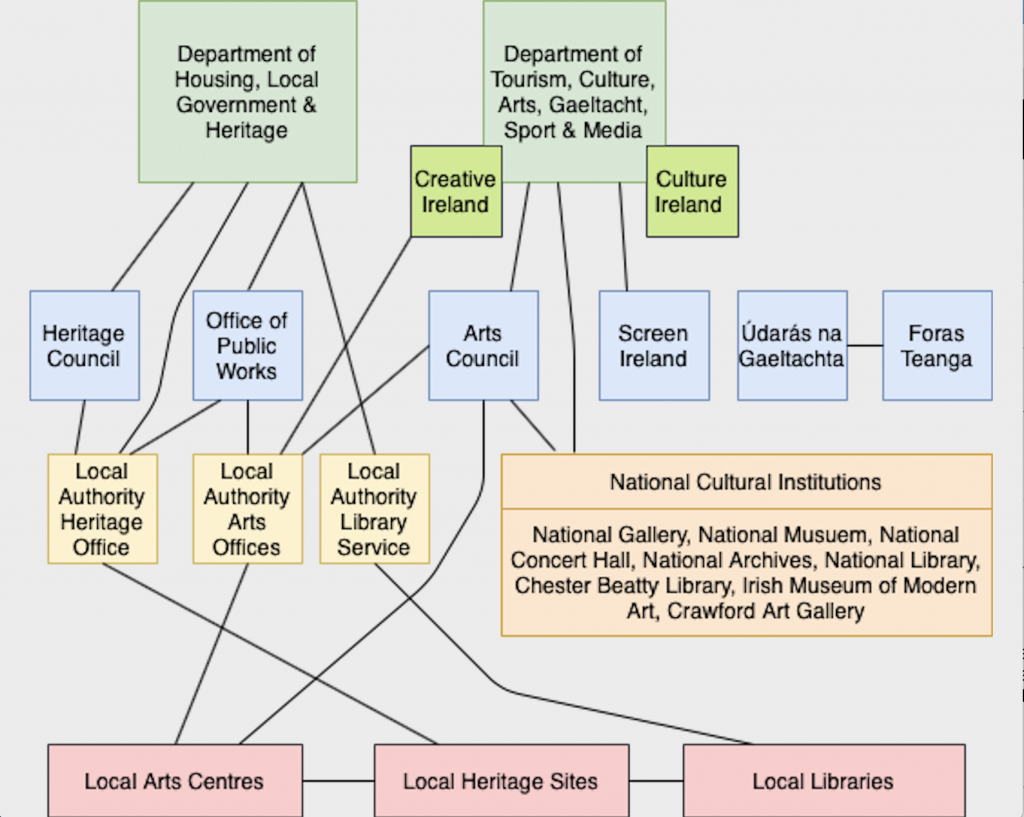

Ireland operates an arm’s length cultural policy model as well as an architect model. The arm’s length model is provided through autonomous semi-state agencies such as the Arts Council, the Heritage Council, Údarás na Gaeltachta or Screen Ireland. The Arts Council is the national agency for the promotion and development of the arts in Ireland. It was established in 1951, to stimulate public interest in, and promote the knowledge, appreciation and practice of, the arts. The Heritage Council was established as a statutory body under the Heritage Act (1995). The Council provides policy advice to government on heritage issues including preservation, sustainability, landscape management, high nature value farming, forestry and climate change.

Support for culture at government level is the responsibility of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media.[1] The Minister/Teachta Dála (TD) in charge of this Department is assigned such responsibility under the legislation of the Arts Act (2003) to promote the arts both inside and outside the state, in consultation with the Arts Council/an Chomhairle Ealaíon. The Minister also has legislative responsibility for Irish heritage under the Heritage Act (2018) and Gaeilge/the Irish language under the Official Languages Act (2003).

The levels of autonomy offered by the arm’s length model have been increasingly limited during the past ten to fifteen years. The expansion of the role of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media represents a shift towards an architect model of cultural policy. This expansion has included the subsumption of the semi-state agency Culture Ireland into the Department, the creation of a new agency/entity within the department called Creative Ireland that has a role of directly funding arts and culture, the Limerick City of Culture project, and various initiatives under the decade of centenaries. These increased roles within the Department with associated funding allocations have occurred during a period of time when the funding allocation to autonomous agencies such as the Arts Council and Heritage Council has remained static. However, it must be noted however that since 2019 funding allocations to these semi-state agencies have been increased, which has gone someway to addressing this balance.

Background

1922-1950: From the foundation of the state in 1921, the arts and culture were initially treated either as an ill afforded luxury or as a representation of previous British colonial rule. With no official legislation for culture or arts, this period was dominated by censorship laws for film and literature. These laws were eventually seen by most as isolating the people from the realities of the world and began to be eroded from the 1960s onwards. However, there were still books and films banned under these legislations up until the 1990s. In 1947 the Cultural Relations Committee (CRC) was established within Department of Foreign Affairs to stimulate cultural activity nationally and promote Ireland’s image abroad.

1950-1970: The arts and culture were officially introduced into the governmental portfolio with the Arts Act (1951). The act establishes the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon as an autonomous semi-state agency to support arts in Ireland. This followed in line with the Keynesian and welfare state model that had been introduced in Britain a few years earlier.

1970-1990: In 1973, amendments were made to the Arts Act, widening the parameters of arts funding to include film and allowing for local authorities to support the arts at a local level. In 1980, the Film Board was established to support the development of film as an industry in Ireland. It was then disbanded in 1987 for six years until its reinstatement in 1993, demonstrating the authority of government to roll back on cultural policy commitments. The first regional arts officer was appointed in 1985. The following ten years, arts officers were appointed in almost every local authority in Ireland, along with a small administrative arts office and small arts programmes.

1990-2000: The Temple Bar Property Company was established in 1991 as a pubic private partnership/semi private agency to develop a 70-acre central area of Dublin City as Cultural Quarter. Eleven nationally significant cultural institutions are established in the quarter. In 1993, the Department of Arts, Culture and Gaeltacht was established, but there was no legislative underpinning for the Department until 2003.

2000-2010: The Arts Act was further amended in 2003 with a wider definition of arts (including dance as well as traditional arts), more authority assigned to the Minister of Arts and compliance from the Arts Council. The act is the first legislation to acknowledge the role of the Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht and increases the Arts Council’s responsibility of reporting to the Department while passing the responsibility of policy making to the Department.

Culture Ireland was established in 2005 as an autonomous semi state body to develop an international platform for Irish arts organisations and individual artists. In 2008, the National Campaign for the Arts (NFCA) evolved as a lobby group of artists and arts workers concerned about impending government cuts on culture and arts. In 2009, the NCFA organised a lobby and successfully curtailed the massive cuts that had been planned. This collective action of the NCFA demonstrated the lobbying power of the arts community in a way that had not been seen previously. However, the planned cuts in arts spending in 2009 (rumored to be 50%) did eventually occur step by step over the course of the following five years.

2010-2020: In 2012, Culture Ireland lost its autonomy when it was subsumed into the Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht. In 2015, the Minister for Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht announced a major cultural budget for commemoration of the 1916 Rising. This increase masked the reality of significant decreases in cultural spending for culture over the previous seven years. In 2016, the Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht launched a national consultation for the establishment of a new cultural policy for Ireland. Ultimately, the legislation remained the same, but the strategy moved towards a focus on wellbeing with the establishment of Creative Ireland in 2017 within the Department.

In 2020: COVID-19 hit the cultural sector very hard. The Government initially responds with artist access to an emergency social payment scheme. The NCFA as well as other groups lobbied heavily for a stronger response. Eventually, the Government responded with additional funding of EUR 25 million. The budget allocation for 2021 has increased funding to the Arts Council from EUR 100 million to EUR 130 million as well as increases for Irish language and Screen Ireland.

[1] Other Departments affecting culture include the Department of Education (having a strong influence via the state schools curriculum in culture and arts); the Department of Rural and Community Development/an Roinn Forbartha Tuaithe agus Pobail (having a strong influence on policy at local authority level); the Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection (having an influence on state support for individual artists); Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment/an Roinn Cumarsáide, Gníomhaithe ar son na hAaeráide agus Comhshaoil (having an influence on press freedom, platforms for culture via public service broadcasting, as well as copyright and digital culture).

Last update: November, 2020

In June 2020, a new government coalition was officially formed. The new department with the main responsibility for cultural policy at a national level is the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media.[1] The goals of the department up to July 2020 were to promote and protect Ireland’s heritage and culture, to advance the use of the Irish language, and to support the sustainable development of the islands. It had overseen the protection and presentation of Ireland’s heritage assets, but this responsibility has now been moved to the Department of Housing.

Capital funding is the main form of support of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media. The department had, until July 2020, directly funded a set of national cultural institutions including National Archives, National Library, National Museums, National Gallery, Chester Beatty Library, Irish Museum of Modern Art, National Concert Hall, and the Crawford Gallery. However, now that responsibility for heritage has moved to the Department of Housing, it is yet unclear how the national cultural institutions will be supported. Issues relating to the day-to-day management of the individual national cultural institutions are dealt with autonomously by the institutions themselves; matters relating to the general policy under which they operate and the provision of financial resources are the responsibility of the Department.

The department operates two cultural agencies within the department with funding capacity: Culture Ireland and Creative Ireland. The Department subsumed the once autonomous agency Culture Ireland in 2012. The agency is responsible for the promotion of Irish arts worldwide through specific grant programmes. Creative Ireland was established within the department in 2017 to enable ‘a cross-government wellbeing […] strategy that places culture and creativity at the centre of our lives.’[2] It has had some limited cross-government cooperative success with regard its Creative Schools initiative.

There are a number of semi-state cultural agencies funded by the department that operate at arm’s length from government. These include the Arts Council, the Heritage Council, Screen Ireland, Heritage Council and Údarás na Gaeltachta. However, the reach of this arm’s length has been shortened during the past twenty years following increased reporting and accountability procedures put in place by the department as well as increases in cultural actions taken on directly by the department, such as Limerick City of Culture, or 2016 Commemorations, or the Decade of Commemorations.

The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon) was established under the first Arts Act in 1951 as a semi-state agency to support arts in Ireland. It is the national agency for funding, developing and promoting the arts in Ireland. The council has always operated as an autonomous body, but the level of autonomy has fluctuated under the aegis of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media. The core functions of the Arts Council under the Arts Act (2003) are to: Stimulate public interest in the arts; Promote knowledge, appreciation and practice of the arts; Assist in improving standards in the arts; Advise the Minister and other public bodies on the arts.[3]

The Arts Council’s main function is to provide financial assistance to artists and arts organisations (but also support other organisations that develop and promote the arts). The council offers advice and information on the arts to government and to other agencies; publishes research and information to advocate for the arts and artists; and supports projects (often in partnership with other organisations) to promote and develop the arts in Ireland.

Screen Ireland (Fís Éireann) is a semi-state agency operating at arm’s length from government. It is the development agency for the Irish film, television and animation industry. The agency provides policy advice for government. According to Variety magazine, “Ireland has become a capital of filmmaking” in recent years, establishing itself as “one of the world’s most attractive production environments”. Screen Ireland supports the industry through a range of grants and investments for development, production and distribution. The agency comes under the aegis of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacth, Sport and Media.

The Heritage Council (An Chomhairle Oidhreachta) was established as a statutory body under the Heritage Act (1995). The Council advises government on heritage policy issues such as conservation, sustainability, landscape management, forestry, high nature value farming, and climate change. They work with their network of local heritage organisations as well as local authority heritage officers. The national brief of the Heritage Council includes natural, cultural and built heritage. The agency operates under state grant from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacth, Sport and Media.

Údarás na Gaeltachta is a semi-state agency that supports the preservation and strengthening of Irish as a living language in Ireland. The agency strives to achieve this objective by supporting communities to live their daily lives through the Irish language, including supporting enterprise and employment and supporting community, cultural and language-based events mainly within Gaeltacht defined regions. The Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Sport, Gaeltacht and Media funds the work of the agency. The Gaeltacht regions (where Irish is the primary language) are recognised in government legislation. There is a very strong traditional arts/folk culture in the Gaeltacht and the people of the Gaeltacht are recognised for their unique dancing, music, crafts and other intangible heritage. The total population of the Gaeltacht is 96,090 (2016 census).

[1] Government policies developed in other departments (ministries) that have direct consequences for cultural policy include the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment (copyright, cultural enterprise), Department of Climate Action, Communication Networks, and Transport (broadcasting, tech) Department of Foreign Affairs and Defense (Irish art abroad), Department of Children, Disability, Equality and Integration (social/cultural inclusion, protection) Department of Education (cultural education), Department of the Housing, Local Government, and Heritage (heritage, local government, including library institutions, local authority arts), Department of Finance (office of public works), Department Social Protection, Community and Rural Development, and the Islands (artists welfare, island cultural heritage) and Department of Higher Education, Innovation and Science (research funding).

[2] https://www.chg.gov.ie/arts/creative-arts/creative-ireland-programme

[3] http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2003/act/24/section/9/enacted/en/html

Last update: November, 2020

As part of the government’s reform of local government as formulated in Putting People First: Action Programme for Effective Local Government (2012), the Local Government Reform Act (2014) provided for the existing eight regional authorities and two regional assemblies to be replaced by three new regional assemblies. The new assemblies were established with effect from 1 January 2015 by the Local Government Act (1991). The aim of the new assemblies is to co-ordinate, promote and support strategic planning and sustainable development as well as promote efficiencies in local government and public services. They do so by drawing up regional spatial and economic strategies in conjunction with the various enterprise and economic development agencies. Culture does appear in Regional Assembly, Regional Spatial and Economic Strategy documents. For example, it appears as an asset (mainly tangible heritage infrastructure) as well as under the principle of healthy place making where creative places contribute to ‘healthy and attractive places to live, work, visit and study in’. Arts and cultural support is not provided at a regional level, but is funded through local authority arts offices. These offices are financed in part from the Arts Council and partly through the local authority.

Last update: November, 2020

Since 2014, there are thirty one local authorities with a total of 949 members known as councilors. Thirty local authorities have an arts office managed by an arts officer. The majority of arts offices operate at a county council level with some at metropolitan level in larger urban centres. The exception to this rule is Dublin County, which is split into four local authority areas, each with its own arts office. Most arts officers are supported by a small staff ranging from one full time staff member to up to eight for the larger local authority areas. This represents the total local authority arts level structure in Ireland.

Support for local arts began to develop from the late 1980s. The Arts Act (1973) enabled local authorities for the first time to support the arts as part of their services, stating that they “may support” the arts. Although this legislative support was in place from 1973, local authorities were slow to recognise the potential benefit or value of adding the arts to their brief. The Arts Council intervened to try and incentivise local authorities by partly funding the arts officer positions. The first local authority arts officer was appointed in 1985, but in the first years of local arts offices there was little funding going directly to the arts. The Arts Council now contributes funding to programming only and the local authorities fund both programming and the arts office personnel.

During the 1990s, cultural development was given a more central role in arts and cultural planning at local level. Since the Arts Bill of 2003, each of Ireland's local authorities is required by government to produce a plan for the arts. As more local authorities began to actively engage in local arts planning, their contribution to cultural policy and cultural funding increased, and this connected cultural planning at a local level with a range of other policy areas. Local authorities’ arts office programmes have helped increase access and participation in the arts in Ireland through removing many of the geographic barriers to participation. There is an arts centre within circa twenty miles of most people in Ireland. Local arts programmes tend to focus on the local impact as a highest policy priority of their strategic plans, which has helped to remove many barriers created by elitist perceptions of the arts. The role of local authority arts officers has more recently been evolving to include a broader cultural remit including such areas as cultural tourism, urban regeneration and creative industries.

The local government authorities rely on a combination of income from both central government via the Department of Housing and Local Government and locally raised income. Local income is raised through rates on commercial and industrial buildings; income from goods and services (housing rents, planning fees etc); exchequer grants (e.g. NDP) etc.

The Creative Ireland programme, which is operated within the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, has attempted to tie a number of policy goals of different agencies together. The Creative Ireland agreements are made between local authorities and the Department of Culture, Heritage and Gaeltacht. The programme is guided by a vision that every person in Ireland should have the opportunity to realise their full creative potential. It is a five-year all-of-Government initiative, from 2017 to 2022, to place creativity at the centre of public policy. Three years into the programme, it has achieved some success with the creative schools initiative encouraging primary schools to engage pupils in creativity. Another success is their partnerships together with local authorities and Music Generation (the national music education programme), which provides access to quality music tuition at a local level in many parts of Ireland.

Last update: November, 2020

Some of the larger privately funded arts organisations in Ireland would include performing arts organisations such as the Gaeity theatre, the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre, or the 3Arena. The music sector in particular is dominated by private organisations. At a performance level, the 3Arena is run by Live Nation who run another three venues. Named the fourth busiest music arena in the world in 2013, it is owned by Apollo Leisure Group (a subsidiary of Live Nation) and is operated by Live Nation Ireland. Live Nation is pursuing the purchase of the Irish concert promotions company MCD. Through their subsidiary Festival Republic, Live Nation also runs most of Europe’s music festivals, including Electric Picnic in Ireland formerly run by POD concerts.

The 2010 merger of Live Nation and Ticketmaster to become Live Nation Entertainment has sparked concern about the controlling monopoly and the over commercialising of the live music experience. A quote from the Live Nation sponsorship website suggests that the concern may be justified: “Through their partnership with Live Nation Ireland, Heineken have had a resounding success amongst a captive audience – gaining market share growth and recognised as a leading brand in music.”

IMRO (Irish Music Rights Organisation) is the dominant player in music licencing collection and also provides some minor levels of funding. The organisation sponsors a number of song contests, music festivals, seminars, workshops, research projects and showcase performances. IMRO’s Music Funding Programme is part of its mission to help foster and develop creativity across all categories of music styles and genres in Ireland today.

Business to Arts is a membership based charitable organisation that acts as a bridge connecting creative partnerships between business and the arts. They offer circa six organisations EUR 80,000 per year under their new stream programme which funds capacity building for arts and cultural organisations to develop their arts fundraising. The annual Business to Arts Awards aim to give recognition to quality sponsorship partnerships.

Fund It was established by Business to Arts as an all-island rewards-based crowdfunding website for Ireland’s creative projects. Most funding through this site is based on individual giving. An area that could be developed further is pier to pier funding and investment funding. At present there are no private grant-making foundations in Ireland focusing specifically on arts and culture.

Last update: November, 2020

Inter-ministerial cooperation is difficult within the Irish model of government, as it requires a transfer of functions order. The Taoiseach, as head of Government (Article 13, Constitution), is responsible for the allocation of functions between Ministers, and for the overall organisation of the government. Arts education policy presents an example of significant attempts at intergovernmental cooperation between government departments, namely the Department of Education and the Arts Council or Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht. There have been numerous cross-departmental committees established from as far back as the 1970s that have produced forward thinking guidelines and recommendations on arts education that were largely ignored by the Department of Education. More recently, action has been taken based on the recommendations of much earlier reports. This suggests a lack of transversal cooperation.

Recent success in transversal cooperation can be seen in the results of some of the Creative Ireland initiatives. This sub division of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media has cross-government policy goals working with the Department of Education, Arts Council, local authorities, and other agencies. The Creative Schools initiative, while underfunded, has achieved some success in developing creative champions in local schools.

The 1% for Arts initiative allows for 1% of budgets on public works to be invested in arts. This includes public works from any department and therefore requires cooperation between departments, local authorities and agencies. This initiative involves an inter-agency group working with the Arts Council.

Last update: November, 2020

The National Cultural Institutions Act (1997) provides that certain cultural institutions hold a special status as National Cultural Institutions. These cultural institutions are given financial resources directly via the Cultural Institutions Unit of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media. Ultimately, this offers a higher level of medium term financial security for such institutions. These institutions are: National Archives of Ireland, National Library of Ireland, National Museum of Ireland (including four museums), National Gallery of Ireland, Chester Beatty Library, Irish Museum of Modern Art, National Concert Hall, Crawford Art Gallery. Overall, the cultural institution infrastructure is quite centralised with a majority based in the Dublin area.

The second layer of cultural institutions attempt to operate at a national level in terms of artistic ambition, but have less financial security. They are reliant on a number of funding sources and must apply competitively to the Arts Council for funding on an annual basis and are not guaranteed funding. These include a wide range in size and type of institutions for example the Abbey Theatre, Dublin; Druid Theatre, Galway; the Gate Theatre, Dublin; Project Arts Centre, Dublin; Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Fire Station Studios, Sculpture Society of Ireland, Cork; Visual & Bernard Shaw, Carlow; Dance Ireland/Dance House, Dublin; The Model Sligo, Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), Dublin. The strategic fund allocated to cultural institutions from the Arts Council can vary a great deal from EUR 10,000 to EUR 7 million dependent upon the scale of the institution and the ambition of funding proposal.

A third institutional layer is supported predominantly by local arts offices, along with some programme funding support from the Arts Council. The main issue faced by such institutions is a tension between meeting the need to stimulate local audience development while also supporting artistic ambition. More often these institutions are reliant on balancing a programme of hosting touring works of national artistic merit along with popular or local productions. These organisations support multiple art forms. Examples would include Rua Red, Tallaght; Draiocht, Blanchardstown; Pavillion Theatre, Dun Laoghaire; Tain centre, Dundalk; Galway Arts Centre; Solstice Arts Centre Navan. Most have been built with the benefit of capital funding under the Arts and Culture Capital Enhancement Support Scheme (ACCESS and ACCESS II) programme between 2000 and 2006. It was envisioned that such centres would break down geographical barriers to participation and encourage cross audience development. While there is strong evidence that participation has increased at the local level, the data is limited in support of the argument that audiences attending one art form became interested in attending another art form as a result of both being in the same building.

A final layer would include private institutions such as performance venues and private galleries. As they are privately funded, they are reliant on commercially viable productions that will allow for sustainability. These organisations include the Bord Gais Energy Theatre, Dublin; the 3Arena, Dublin; the Gaeity Theatre, Dublin; Kerlin Gallery, Dublin; Molesworth Gallery, Dublin.

Last update: November, 2020

Table 1: Cultural institutions, by sector and domain

| Domain | Cultural institutions (subdomains) | Public sector |

| Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage sites (recognised) | 780 (2003) |

| Archaeological sites | 150800 (2020) | |

| Museums | Museum institutions | 140 - 186 (2016) |

| Archives | Archive institutions | 212 (2005) |

| Visual arts | Public art galleries / Exhibition halls | 69 (2016) |

| Performing arts | Scenic and stable spaces for theatre | 82 (2020) |

| Theatre companies | 90 (2020) | |

| Dance and ballet companies | 1 ballet & 15 dance (2020) | |

| Symphonic orchestras | 2 (2020) | |

| Libraries | Libraries | 330 (2019) |

| Audiovisual | Cinemas | 463 (2018) |

| Broadcasting organisations | 2 (2020) | |

| Interdisciplinary | Socio-cultural centres / cultural houses | 138 (2018) |

Sources:

Heritage Ireland; Heritage Council; Irish Museums Survey/Irish Museums Association; National Monuments Service, Sites and Monuments Record (SMR) database; Arts Council; Visual Artist Ireland; Irish Theatre Institute; Statista; Department of Rural and Community Development; Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications.

Last update: November, 2020

The National Cultural Institutions Act (1997) changed the relationship of government to a number of key cultural institutions in Ireland. The Act provided for the establishment of the Museums Board of Ireland (Bord Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann) and the National Library Board (Bord Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann). The Act also provided for a new framework of support for national heritage. It is as yet unclear which department will continue the support of these national cultural institutions, as responsibility for heritage has been moved in 2020 from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media to the Department of the Housing, Local Government and Heritage. Up until 2020, the Department of Culturedirectly funded national cultural institutions including National Archives, National Library, National Museums, National Gallery, Chester Beatty Library, Irish Museum of Modern Art, National Concert Hall, and the Crawford Gallery. Issues relating to the day-to-day management of the individual national cultural institutions are dealt with directly by the institutions themselves; matters relating to the general policy under which they operate and the provision of financial resources are matters for the related department.

The Office of Public Works (OPW) is a government office with responsibility for state-owned and protected national monuments, sites or properties in Ireland. OPW Heritage Services is tasked with conserving these heritage sites as well presenting these sites to visitors. An increased trend has been the utilisation of heritage by government as an instrument in the development of brand Ireland and its tourism products. The OPW maintains and presents Ireland’s most iconic heritage sites, including Ireland’s two World Heritage sites, 780 national monuments and over 2,000 acres of gardens and parklands. The OPW is also responsible for the management of the State Art Collection which comprises of c.16,000 works. These works include both historical and contemporary works including paintings, prints, sculpture, fine and decorative art objects, music, as well as poetry. The National Monuments Service, Historic Properties Service and Visitor Services operate the OPW Heritage Services.

Increased partnership now occurs at a local authority government level between heritage and arts offices. A Framework for Collaboration: An Agreement between the Arts Council and the County and City Management Association highlighted the value and clarified the current position of the 30-year strategic partnership between the Arts Council and local authorities nationwide, and agreed a vision and broad goals for what can be achieved collaboratively over the next ten years.

Public cultural institutions in Ireland have been greatly affected by many years of austerity following the economic recession of 2008. An embargo on recruitment combined with stagnation and cuts in funding have greatly curtailed the development of cultural institutions. This austerity lifted slightly since 2017 with minor infrastructural investments from government mainly dealing with legacy buildings' maintenance issues. A number of institutions have also been highlighted for future major investment such as the National Abbey Theatre in Dublin. The stagnation of funding to cultural institutions during the years of austerity lead to changes in employment practices with the introduction of short-term contracts, Jobsbridge internships (a national internship scheme that provides work experience placements for a six or nine month period), as well as outsourcing of production.

Last update: November, 2020

The Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media co-funds two of the six cross-border implementation bodies established under the terms of the British-Irish Agreement Act (1999). The instrumental use of culture in sustaining international relations is important to the Irish Government. Previous to the establishment of Culture Ireland in 2005, the promotion of Irish culture internationally was supported via the Cultural Relations Committee (CRC), a much smaller agency which was a minor sub department attached to the Department of Foreign Affairs (1948-2004.)

In 2005, Culture Ireland was established as a stand alone, autonomous agency with the role of supporting the development of international opportunities for Irish arts organisations as well individual Irish artists. For a time the agency operated at arm's length with considerable freedom and without a remit to operate solely for the purpose of cultural diplomacy, which was quite a change from the CRC.

In 2012, Culture Ireland was subsumed into the Department of Culture, Heritage and Gaeltacht. While this relocation was deemed by Government as an essential organisational re-configuration of state institutions under crisis conditions after entering the EU-IMF loan programme, it has resulted in much reduced autonomy for the agency. Culture Ireland’s current role is to promote Irish arts worldwide by creating and supporting opportunities for Irish artists and companies to present and promote their work at strategic international festivals and venues. They develop platforms to present “outstanding” Irish work to international audiences, through showcases at key global arts events, such as the Edinburgh Festivals, SXSW Texas, WOMEX or the Venice Biennales.

There are three strategies at work in Culture Ireland. Because of the scarce resources of the agency, they have strategically focused on specific geographic territories such as the United States in 2017, and Britain in 2018. The second strategy is supporting Irish artists and arts organisations to travel internationally. In 2018, this strategy allowed Irish artists to travel to 55 countries and reach a combined international audience of 5.5 million people. The third strategy is to financially support special initiatives, such as the EUR 3.5 million for Imagine Ireland Fund in 2011, EUR 1.9 million for EU Presidency in 2013, and EUR 2.5 million for the cultural fund I am Ireland in 2016. This recent strategic funding is more politically motivated and dependent on the motivations of the Minister of the Department than an autonomous strategy informed by cultural policy expertise.

There has been an initial period of increased funding for Culture Ireland in the past, from EUR 2 million in 2005 to EUR 4.7 million in 2008, which was followed by a decrease down to EUR 2.5 million between 2010 and 2015. In 2018, the funding was increased again to EUR 4 million.

A 2015 review of Ireland’s foreign policy undertaken by the Department of Foreign Affairs stated that ‘Irish culture is a global commons, recognised and followed by people who may have no other connection to Ireland.’ The review also stated that ‘through cultural diplomacy, the relationship we have built with our diaspora communities and the partnerships we have forged around the globe can only be strengthened.’ Initiatives such as the Gathering 2013 and the 2016 Commemorations have strategically used culture as an instrument to connect with the Irish diaspora.

It is worth noting that the lobbying power of cultural agencies in Ireland is limited relative to their levels of autonomy. Culture Ireland was unable to criticise government because it was in the direct employment of government during a time of critical underfunding of its agency and increased government instrumental use of the cultural budget. While the case for cultural funding is made internally, there is an inability for such cultural institutions to lobby for public support.

Last update: November, 2020

Ireland is a (founding) member of the Council of Europe. The Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs engages with the Committee of Minister of the Council. Ireland is a member of the European Union, joining the European Economic Community in 1973. Concerns were expressed during the two Lisbon referendums in Ireland in 2008 and 2009 about the ‘constitutionalising’ of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and about the potentially expanding reach of EU law. The main concern was that key decision-making by the Irish judiciary on aspects of fundamental rights might be supplanted in practice by the European Court of Justice. These concerns were not matched by the reality since the referenda. Most aspects of Irish life have improved through EU membership. Ireland was a net recipient of European funds up to the 2014-2020 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) EU budget, but is expected to become a net contributor within the next framework 2021-2027. Ireland’s recovery from the financial crisis was aided by a three year EU/IMF financial assistance programme that ran from 2010-2013. Much of Ireland’s cultural infrastructure has benefited from EU structural funds and regional funds.

Ireland participates in Creative Europe and Horizon programmes of the European Commission. However, participation rates are lower than most other EU states. A Creative Europe desk supporting cultural projects is operated out of the Arts Council. For media support and advice, there is a Creative Europe MEDIA desk in Dublin and in Galway. Cross-sectoral support and advice is then offered across all three Creative Europe desk offices.

The Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, along with the Arts Council, has responsibility for implementing and monitoring the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions.

Last update: November, 2020

Numerous arts and culture institutions are engaged in transnational cooperation, ranging from major institutions to small cultural initiatives. Cooperation projects have either followed long standing relationships established through cultural diplomacy; availed of European funding from Creative Europe or Horizon 2020; or been supported through Culture Ireland to promote Irish arts and culture internationally. Arts and cultural institutions have engaged in activities such as festivals (music, film, etc.), exhibitions (art fairs, Biennale, architecture, photography etc.), conferences and workshops, information and training programmes. Professional cooperation activities within European and international networks include Culture Action Europe, European League of Institutes of the Arts (ELIA), European Network of Cultural Administration Training Centres (ENCATC), International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts (IETM), International Council of Museums (ICOM), International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), International Federation of Arts Councils and Cultural Agencies (IFACCA).

There is a limited network of Irish arts and cultural centres internationally. For example, the Irish Cultural Centre/Centre Culturel Irlandais (CCI) in Paris has established a longstanding relationship with the city. The Centre presents the work of contemporary Irish artists, reinforces the rich heritage of Franco-Irish relations and fosters a vibrant and creative resident community. In addition to its diverse cultural programme, the CCI houses France’s primary multi-media library of resources on Ireland as well as significant historic archives and an old library. Inaugurated in 2002, the CCI is situated in the Collège des Irlandais, or Irish College, formerly home to a large collegiate community of Irish priests, seminarians and lay scholars whose origins stretch back to 1578. The Fondation Irlandaise has overseen the building since the Consular Decree of Napoléon Bonaparte consolidated the former Irish, English and Scots foundations and colleges in Paris into the Collège des Irlandais. The Fondation acts as a board comprising French and Irish members; it appoints the director and staff of the Centre Culturel Irlandais. The cultural programme of the centre is organised in partnership with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Culture Ireland and with the sponsorship from the Arts Council of Northern Ireland and the British Council.

The London Irish Centre organises a cultural programme of Irish arts and culture. The centre was set up as a charity to relieve and combat poverty, distress, financial hardship and sickness; to relieve those in need by reason of youth, age, ill health, disability, unemployment or other disadvantage; to promote Irish art, culture and heritage for the public benefit; and to advance education for the public benefit in Irish culture and language. The centre is supported through a range of partnerships from the Government of Ireland: Emigrant Support Programme; Culture Ireland; Irish Youth Foundation; the Ireland Funds; City of London; along with commercial and charitable sponsorship from Allied Irish Bank and others.

Founded in 1972, the Irish Arts Centre (New York) based in Manhattan is dedicated to projecting a dynamic image of Ireland and Irish America for the 21st century; building community with artists and audiences of all backgrounds; forging and strengthening cross-cultural partnerships; and preserving the evolving stories and traditions of Irish culture for generations to come. The centre’s multi-disciplinary programming operates in three core areas: performance — including live music, dance, theatre, film, literature, and the humanities; visual arts — including presentations and cultural exhibitions that tell the evolving Irish story; and education — with dozens of classes per week in Irish language, history, music, and dance.

The Irish Government has recently invested capital funding towards updating the infrastructure of a number of the international cultural centres, including EUR 2.5 million towards the EUR 60 million capital costs for a new building in New York City. The new building is due for completion in 2020.