1. Cultural policy system

Italy

Last update: May, 2022

Objectives

In the Italian Constitution, the main legislative reference in cultural matters is represented by Article 9, which states: “The Republic promotes the development of culture and scientific and technical research. It protects the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation”. The main legislative implementation of Art. 9 is due to the Heritage and Landscape Codex, adopted by Leg. Decree 42/2004,that synthesized in a single text a large number of previous specific laws (see chapter 4.2.2).

Within the broader framework of the cultural objectives pursued by the 1947 Constitution - heritage and landscape protection, cultural development, pluralism and freedom of expression - “heritage” has traditionally been the main focus of cultural policy, starting from the name of the first Ministry established in the mid-70s: Ministry for Heritage (Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali).

The prominence of heritage as the cornerstone of our cultural policy was thus emphasized: “safeguarding” and “restoration” being the key functions absorbing most of the financial resources allocated to the cultural field. Support for contemporary creativity and wider access continued to be a low priority, as stated by the Council of Europe in 1995: “at the hint of any conflict between tutela and public access, the public were invariably the loser”.

As specified in the following sections, moreover, the fundamental competences of this Ministry are quite wide on different cultural domains, including performing arts, libraries, film, landscapes, etc. The following more detailed objectives for government action had been defined by Leg. Decree 368/1998, creating the new Ministry of Heritage and Cultural Activities:

- the protection and valorization of cultural heritage;

- the promotion of reading and of books and libraries

- the promotion of urban and architectural quality;

- the promotion of cultural activities, with particular reference to the performing arts, film and the visual arts;

- the support of artistic research and innovation;

- higher training in all cultural disciplines;

- the diffusion of Italian culture and art abroad.

These matters still remain the basis of government action, although between 2006 and 2021 a series of legislative decrees have partially changed the areas of competence of the Ministry (for example with respect to the tourism sector) and its organizational structure (see chapter 3.1 and 4.2).

Although there is no automatic correlation of these objectives with the cultural policy principles of the Council of Europe – promotion of identity and diversity, support to creativity – they appear to be well connected with identity and creativity issues, and in some way with participation. On the other hand, the goal of promoting diversity in cultural life as a whole has not yet become a real priority for our national cultural policy (see chapter 2.5).

Main features

There is no official definition of “culture” in Italy, nor are the boundaries of the cultural field outlined in a rigid way by government action. The rationalization of most of the cultural competencies under one single Ministry was, actually, the outcome of a very long and fairly empirical process.

However, Italy has always been actively involved in the process to establish a common definition of culture, carried out by international organizations, as a precondition for pursuing statistical harmonization and comparability among countries[1]. The original Eurostat definition of the cultural sector, agreed upon by the Italian and the other EU governments, covered the following domains: heritage; archives; libraries; visual arts and architecture; performing arts; books and the press; cinema and the audiovisual sector. Crafts and advertising have also been added in 2013.

The Italian cultural policy model may be considered from an economic and an administrative point of view.

The economic model is closely connected to a mixed economy system, with the public sector historically being the primary funding source for heritage, museums, archives and libraries, and, to a certain extent, for the performing arts, whereas the cultural industries are mainly supported by the marketplace, although supplemented by public subsidies in case of poor market performance (see chapter 7.2). On the other hand, heavy constraints on the national budget induced public authorities of all levels of government to encourage a direct involvement both of the non-profit private sector and of the marketplace, even in the fields of heritage and the performing arts.

Art. 117 of the Constitution includes, among the matters reserved to the exclusive legislation of the State, the protection (tutela) of cultural heritage, while among the matters of concurrent legislation between the State and the Regions, are those relating to the valorization (valorizzazione) of cultural and environmental heritage and the promotion and organization of cultural activities, leaving any other aspect to the regional legislation. Particularly relevant is also the constitutional “principle of subsidiarity”, on the basis of which private individuals can participate in activities of general interest, especially if they are owners of cultural assets (see chapter 4.1.1).

As far as government action is concerned, the administrative model has traditionally been one of direct intervention of public administration in the support of cultural activities, and, in many cases, in the management of cultural institutions (museums, sites, theatres, etc.) through national Ministries or local ad hoc departments. However, at the national level, a few quasi-independent public bodies do exist and, since 2014, some major state museums have been the object of a process of reorganization that has implied a significant economic and organizational autonomy (see chapter 1.3.3).

Background

Italy is a comparatively young state, whose unification dates back only to 1860. The first laws pertaining to cultural matters were adopted by the Parliament in 1902 and 1909, focusing mainly on safeguarding a limited complex of monuments considered to be of national interest. In fact, given the unparalleled wealth of the multi-layered Italian historic and artistic assets and the considerable burden of its maintenance on the public purse, heritage has always represented the prevailing domain of public policy in the cultural sector.

A noteworthy parenthesis to this longstanding trend was to be witnessed during the 1920s and 1930s under fascist rule, when Italy was one of the first countries to create a ministry specifically in charge of the cultural sector: the Ministry for Popular Culture. Despite the negative implications of such a Ministry being created under a dictatorship – censorship, ideological propaganda, etc. – the farsightedness and the anticipatory view of the role of the State in the policies for culture of the fascist regime are by now generally acknowledged.

A large part of Italian cultural legislation dates back to the late 1930s and early 1940s, and many fundamental regulatory references of the time were incorporated into subsequent regulations and remained in force until the 2000s[2]. The same is true for the surviving major cultural institutions: the Institute for Restoration, the national broadcasting company (RAI), Cinecittà and Istituto Luce.

As in Germany, our Ministry for Popular Culture was immediately abolished after the war: yet, whereas cultural competencies were devolved to the Lander in the former case, in Italy they were instead retained by the State and split among several Ministries. As already highlighted, the constitutional principle of protection of cultural heritage was actively pursued from the outset, whereas the promotion of cultural development remained for decades in the background. Thus, for a long time, support for contemporary creativity and access to the arts were not considered a priority. Participation in cultural life gradually gathered momentum through the cultural industries, the high level of film production and the new mass medium: television.

A relevant institutional turning point came with the decentralization process, when the 15 ordinary Regions that were foreseen by the 1947 Constitution were finally established in 1972. Active cultural policies were in fact undertaken by some of the Regions, aware of the potential of culture to assert their own identities, soon followed by the Municipalities (see chapter 1.2.3). When regional and municipal departments for culture were embedded in most local administrations, the call for a broader participation in cultural life became a widely debated national issue.

Other relevant institutional changes emerged in 1974, when a separate Ministry for Heritage was created by regrouping responsibilities for museums and monuments, libraries, cultural institutions from the Ministry of Education, for archives from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and for book publishing from the Prime Minister's Office[3].

At the turn of the last century, the central role acquired in Italy by cultural policies, in the framework of development policies, played a significant role in removing the last obstacles to a full rationalization of the state cultural competencies. In 1998 the scope of the Ministry for Heritage was extended to embrace responsibility for the performing arts and cinema, previously entrusted to the Ministry of Tourism. When further responsibilities on copyright were added in 2000, the Ministry of Heritage and Cultural Activities (MiBAC)had finally achieved the full status of a ministry for culture[4]. In 2013 the Ministry was further empowered with responsibilities on tourism, thus being renamed the Ministry of the Heritage, Cultural Activities and Tourism (Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali/MiBACT). Recently the responsibilities on tourism have been transferred for a short while to the Ministry of Agricultural Policies and then (2021) to a new autonomous Ministry of Tourism. On this occasion also the acronym “MiBACT” changed again becoming simply “MiC”, Ministry of Culture, (Ministero della Cultura).

[1] Action was undertaken first by UNESCO's Framework for Cultural Statistics, followed by the EU's Eurostat Working Group on Cultural Statistics and, subsequently, by ESSnet- Culture.

[2] Not only on the protection of heritage and the landscape (reference is made in particular to Law n1089/1939, known as “legge Bottai”), but also in support of artistic creativity, such as the comprehensive Copyright Law, or the Law on “2% for the arts in public buildings”.

[3] The transfer of responsibilities for the performing arts to the new Ministryturned out to be premature at the time.

[4] Only responsibilities for support and regulation of television, radio and the press, as well as arts education, remained out of its reach.

Last update: May, 2022

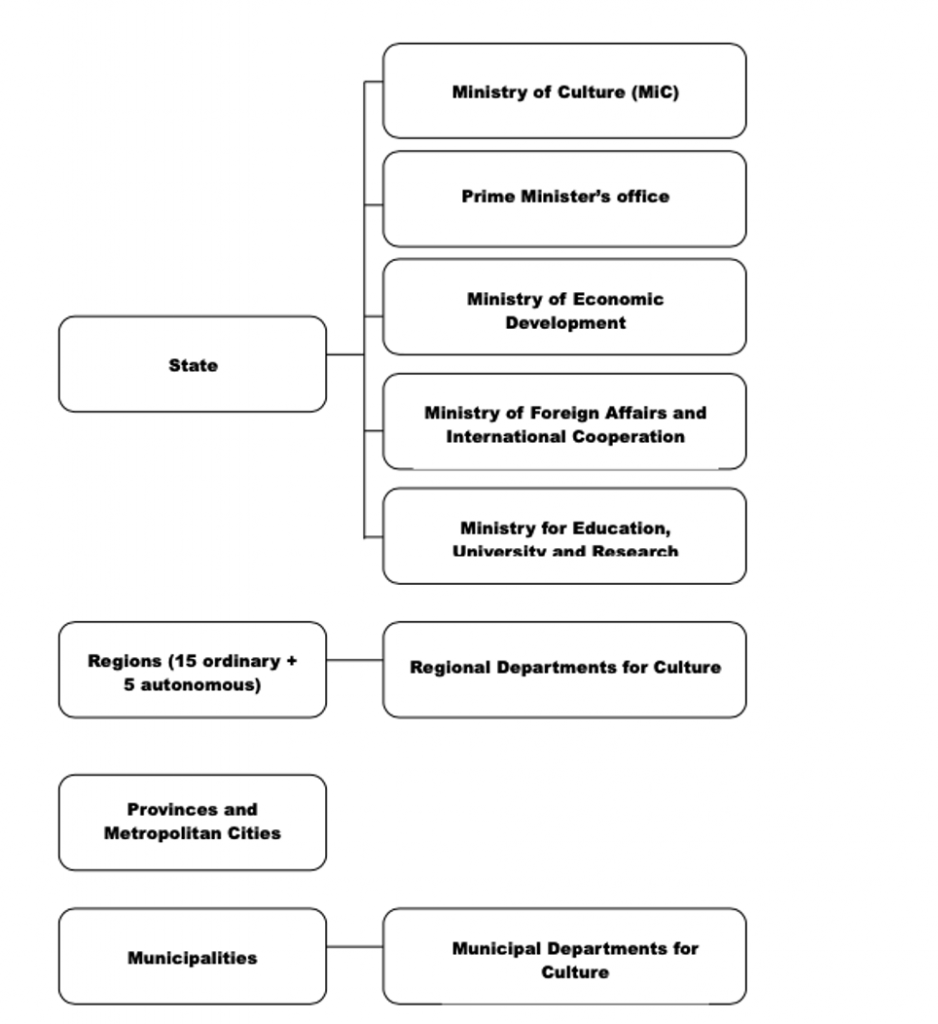

Chart 1 provides a schematic overview of the organizational structure of cultural administration in Italy at different levels of government.

Regarding the relationship between the national and sub-national levels, the Constitution guarantees both local self-government and the subsidiarity principle. It gives indications on the exclusive competencies of the State, concurrent competencies, and exclusive competencies of the Regions. Residual competence is vested in the Regions.

Chart 1: Institutional structure of cultural administration at different levels of government

In Italy four levels of government – State, Regions, Provinces and Municipalities – share responsibilities in the cultural field, although the most important administrative and legislative functions still lie with the State.

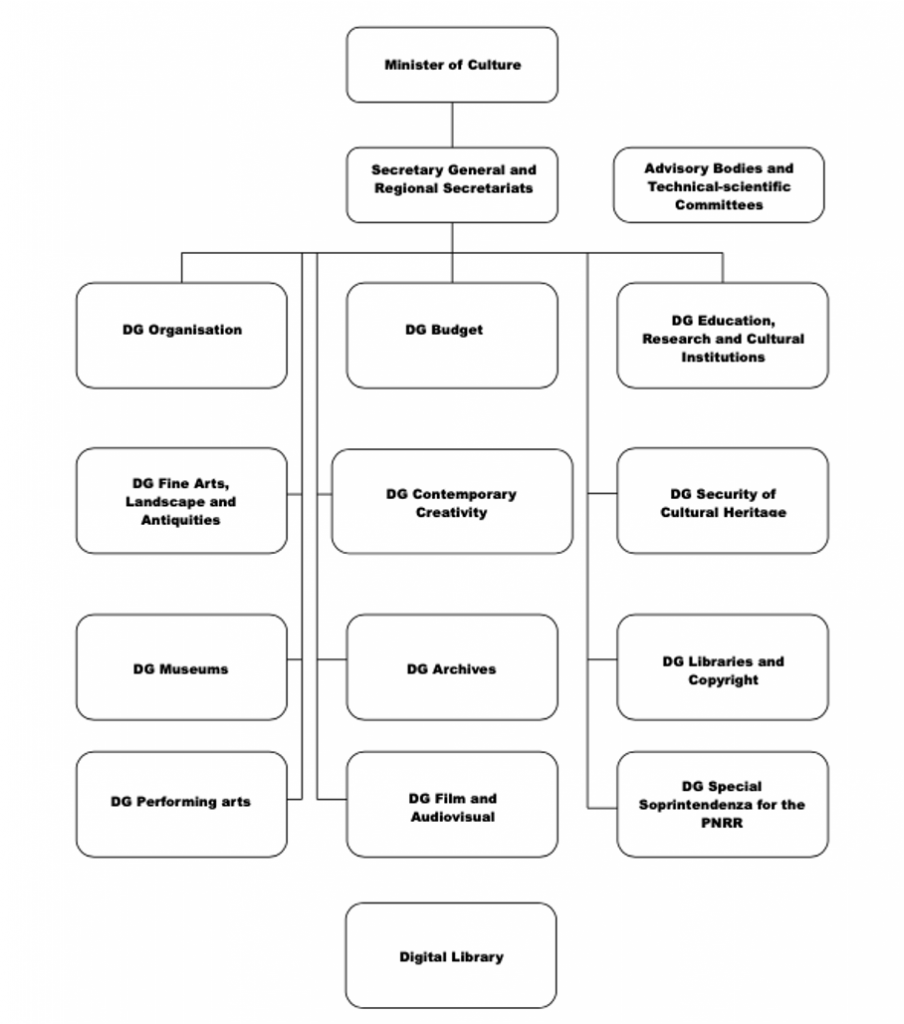

Chart 2 shows the organisational structure of the new Ministry of Culture (MiC) provided for by the Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers 123/2021[1].

Chart 2: Institutional Structure of the Ministry of Culture

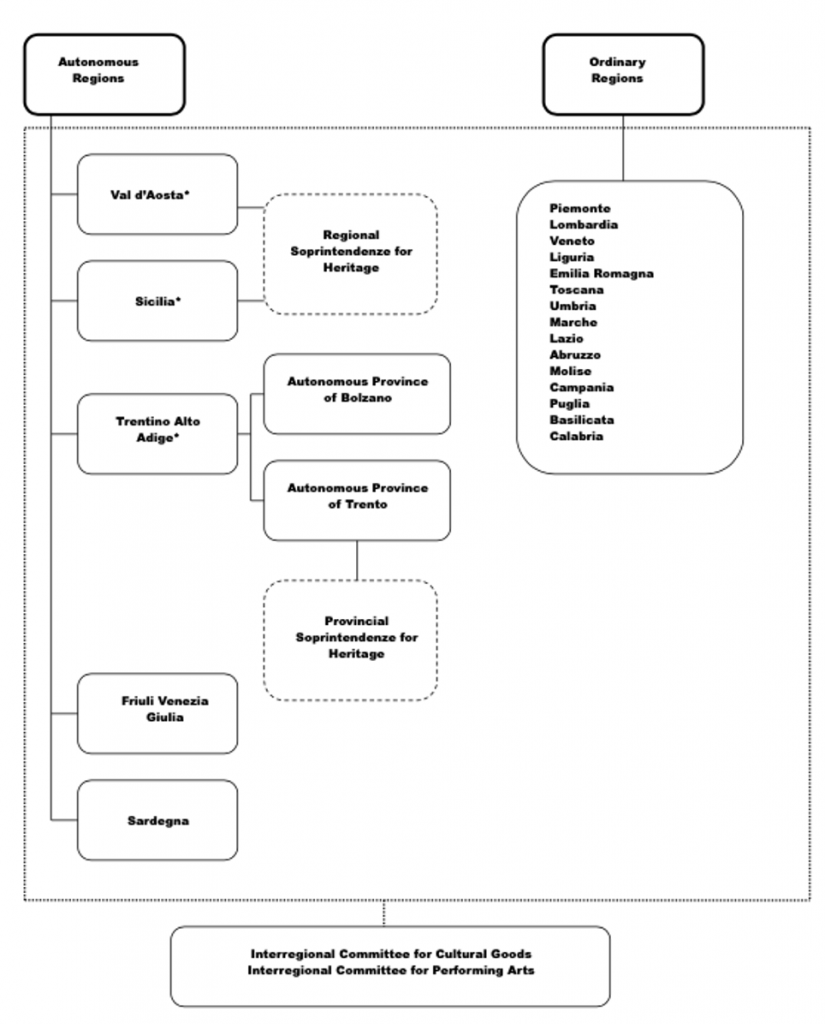

As shown in Chart 3, all 20 Italian Regions have regional departments for culture and special responsibilities for heritage are entrusted to the autonomous Regions of Valle d’Aosta, Trentino-Alto Adige and Sicily.

Chart 3: Autonomous and ordinary Regions in Italy

[1]Source: https://media.beniculturali.it/mibac/files/boards/be78e33bc8ca0c99bff70aa174035096/DECRETI/PDCM/PDCM%20del%2024%20giugno%202021%20n123.pdf

Last update: May, 2022

Administrative functions

At the national level, responsibilities for the cultural sector lie presently with 4 Ministries (see Chart 1).

The Ministry of Culture (MiC)

Chart 2 shows the new organizational structure of the Ministry provided for by the Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers 123/2021.

As previously illustrated, over the years, the Ministry has undergone several transformations at organizational and functional levels. After a long-lasting separation of functions between cultural heritage and the performing arts, at the end of the past century, the Ministry has been entrusted with the full range of core cultural functions: heritage, museums, libraries and archives, visual arts, performing arts and film, cultural institutions, copyright, with the only exception being communications (radio television and the press). Tourism has been the responsibility of the Ministry in two periods: from 2013 to 2018 and from 2019 to march 2021, when the responsibilities were transferred for a short while to the Ministry of Agricultural Policies and then to a new autonomous Ministry of Tourism.

In managing national heritage institutions, just under 500 museums with archaeological sites and monuments fall under the direct responsibility of the Ministry of Culture, out of 5.000 in total. About a hundred libraries out of about 7.400 and a hundred archives also fall under the direct responsibility of the Ministry, while the whole domain of protection and valorisation of heritage is regulated by the Heritage and Landscape Codex (see chapter 3.1 and 4.2).

At the central level, the coordination of ministerial functions is entrusted to a Secretary General, which directs and coordinates both 13 General Directions (DGs) and 17 regional Secretariats. Recently the DG for Tourism has been assigned to the Ministry of Economic Development, untying it from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in which it was previously based (see chapter 3.5.6).

In exercising its functions, the Ministry is assisted by four central, widely representative “advisory bodies” (the High Council for Heritage and Landscape, the "Consulta" for the Performing Arts, the Permanent Committee for Copyright) and by seven technical-scientific committees on specific thematic areas.

The DGs are technically supported by other relatively autonomous specialized “scientific bodies”, including the Istituti centrali for Heritage protection and restoration, for Heritage cataloguing, for Books restoration and cataloguing, for National Archives, for Demo-ethno-anthropological goods, for Graphic arts, for Audiovisual Goods, and the Opificio per le Pietre Dure.

Since 2014, some of the major state cultural sites have gradually acquired economic and managerial autonomy. Now there are 44 cultural institutes (museums and archaeological areas) with special autonomy, coordinated by the General Direction of Museums, whereas the other national museums are organised under the Regional Directions of Museums (see chapter 3.1).

In Italy the public State libraries are managed directly by the Department of Libraries and Copyright of the Ministry of Culture (see chapter 4.2.5). Since 2016, Archival and Bibliographic Superintendents have been established in all Regions, with the exception of those with a special statute.

The promotion of books and press is in the charge of the DG Libraries and Copyright. The DG’s activities range from promoting reading, to coordinating libraries and the national library system. In 2019, the Central Institute for the digitization of cultural heritage - Digital Library was created. It coordinates the digitization programmes of cultural heritage under the Ministry’s responsibility and will also be responsible for projects for the digitization of cultural heritage which will be funded with the resources allocated by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (see chapter 3.5.2).

The MiC, through the Directorate General for Film and Audiovisual matters, carries out support activities both for film production, distribution and dissemination, supporting institutions, enterprises, cinemas and festivals throughout the national and international territory (see chapter 3.5.3). In 2001 the administration of cultural heritage endowed itself with a body dedicated to the promotion, incentivisation and enhancement of contemporary creativity, through the establishment of a DG for Contemporary Arts and Architecture. The office has undergone several changes over time and in 2019 its name was changed to the DG for Contemporary Creativity, bringing together policies in a vast field of action: from cultural and creative businesses to contemporary art, photography, fashion, and urban suburbs (see chapter 3.5.5 and 4.2.4).

The MiC performs also a wide range of activity in the field of education through its DG for Education, Research and Cultural Institutions, which holds and carries out functions and tasks relating to coordination, design and assessment of education, training and research programmes in the area under the responsibility of the Ministry (see chapter 5.1). Still in the field of higher education, in 2014 the Ministry of Culture founded the “Fondazione Scuola dei beni e delle attività culturali” (Foundation School of Cultural Heritage and Activities): an international institution dedicated to training, research and higher education. It carries out activities of lifelong learning and retraining for cultural heritage professionals, aimed at supporting changes in the cultural system also by a strong internationally-oriented approach[1].

At the peripheral level, the MiC is split between administrative bodies – the Regional Secretariats – and techno-scientific territorial structures especially endowed with the mission of safeguarding heritage at the local level: the Soprintendenze, respectively related to the DG for Fine Arts and Landscape and for Antiquities.

Besides the MiC, other Ministries and institutional entities are also involved in cultural matters. The main ones are:

The Prime Minister’s Office

The responsibilities for the allocation of financial support to the press, and for the conventions related to RAI (the state agency for radio and television) for providing additional public services - broadcasting abroad, etc.- are exercised by the Department for Information and Publishing of the Prime Minister’s Office, headed by an Undersecretary of State for Information and Publishing.

The Ministry of Economic Development

Responsibilities for the media and ICT regulatory functions as well as for financial support to local radios and television networks are entrusted to an Under Secretary for Communications, attached to the Ministry for Economic Development. Its regulatory functions are carried out jointly with AGCOM (Authority for Guarantees in Communications) (see chapter 4.2.6).

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (MAECI)

The Ministry’s responsibilities for international cultural cooperation are mainly exercised in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture (see chapter 1.4).

The Ministry of Education, University and Research

Since 2020, the Ministry has been split into two departments by a decree law, one the Ministry of Education and the other the Ministry of Universities and Research, also comprising a General Direction for Higher Education in the Arts, Music, and Dance, which is the main institution responsible for artistic and cultural education (see chapter 5.1).

Legislative functions The State exercises exclusive legislative powers in cultural heritage protection. Legislative functions lie presently with the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, and are notably exercised through their respective Cultural Commissions. Besides the specific legislation in cultural matters, the yearly adoption of the Budget Law presently allows both Chambers to play a relevant role in the funding system, as the Parliamentary debates on this law often produce heated discussions on the pros and cons of public financing of culture (see chapter 7).

Last update: May, 2022

The twenty Italian Regions – all endowed with legislative powers and ad hoc administrative structures in the cultural sector (regional departments for culture / “Assessorati regionali alla cultura”, in some cases associated with other domains like education and tourism) – are split into two groups (see chart 3):

- Five autonomous Regions, created in the post-war period and endowed with more extended competencies in the cultural field. Out of these five autonomous Regions, according to their statutory laws, three – Valle d’Aosta, Sicily, and Trentino-Alto Adige – also exercise, through their decentralised Soprintendenze, exclusive and direct legislative and administrative responsibility for their own heritage assets, including the previous “national”, now “regional”, museums and sites. The devolution of functions by the State took place in the late 1970s. Therefore, in these three Regions there are no state Regional Directions for Cultural Goods and the Landscape;

- Fifteen ordinary Regions, established in 1972, whose cultural competencies were initially limited by the Constitution (Article 117) to the supervision and financial support of local museums and libraries. The subsequent devolution of responsibilities for “cultural promotion of local interest” (Law 616/1977), although falling short to meet their demand for more cultural decentralization, came as a partial acknowledgement of their active commitment in the field, the formula being vague enough to eventually allow the Regions to legislate on a fairly wide range of cultural disciplines. According to the subsequent so-called “Devolution Laws” adopted in the late 1990s, and to Constitutional Law 3/2001, ordinary Regions have now concurrent legislative powers with the State as far as managing and enhancing heritage and cultural activities are concerned.

The Regions have legislative power with respect to any matters not expressly attributed to the State or to the concurrent legislation. In particular, the development of cultural and environmental resources is a matter of concurrent legislation, for which the State only set fundamental principles. Therefore, with an approach based on vertical subsidiarity, Italian Regions carry out specific activities on several areas of cultural policy. For example, they support many training actions, covering the different educational available options of lifelong learning and continuous education in the cultural field, primarily together with the Ministry of Labour and the European Social Fund (see chapter 5.5). Moreover, in the Film and Audiovisual sector, governed in Italy by various regulations and institutes, many regional administrations have specific policies that are usually developed by regional Film Commissions (see chapter 3.5.3).

Last update: May, 2022

The Provinces

The Legislative Decree 267/2000 regulates responsibilities of Provinces, the level of government least involved in cultural policy. Since the entry into force of Law 56/2014 (“Riforma degli enti locali”), Provinces are no longer an elective body and are considered as territorial bodies for wide areas (“Enti di area vasta”) with limited functions, as required by wide territorial areas and/or as requested to support local municipalities.

Currently, there are 107 Provinces, of which 14 are Metropolitan Cities (namely Rome, Milan, Naples, Turin, Bari, Florence, Bologna, Genoa, Venice, Reggio Calabria, Palermo, Catania and Messina and Cagliari), and two correspond to Autonomous Provinces. According to Law 56/2014, they are recognized as ordinary administrative entities of second level and functions previously performed by Provinces have been mostly devoted to Regions.

This reorganization process is still in a transitional stage, in which governance models are not yet consolidated and usually respond to ad-hoc agreements between the different administrative entities. The new definition of responsibilities of Provinces and Metropolitan Cities often responds to local government needs and faces difficulties derived from the rescaling and transfer of competencies from heterogeneous entities. Thus, it is not yet possible to evaluate the impacts on the former provincial culture-related functions, mainly concerning archives and libraries as well as their role of intermediating bodies between the Regions and the municipalities for the allocation of funds to cultural activities.

The Municipalities

Along with the State, the nearly 8.000 Municipalities are undoubtedly the most prominent public actors and funding source in Italy’s cultural scene. Administrative responsibilities of these entities[1] include cultural services and infrastructures (such as local museums, exhibition halls, multifunctional cultural centres, cultural activities and theatres).

The provision of local cultural services varies greatly across the Country, and the State has no direct competence in this matter, which is rather dealt with on a voluntary basis by the municipalities (see chapter 6.4). Through their departments for culture(“Assessorati alla cultura”), they play a paramount role in the direct and indirect management of municipal cultural institutions (see chapter 4.1.2). They even promote and support a wide range of cultural activities, actively contributing to the rich national supply of art exhibitions, performing arts festivals, literature festivals, street events, cultural minorities’ celebrations, etc. Italian municipalities are also investing highly in the restoration and maintenance of their historic assets, albeit under the supervision of the Ministry, and in building cultural premises, with special attention given to capital investment in cultural infrastructure and, in particular, in modern and contemporary art museums and performing arts centres.

[1] Art. 13 of Legislative Decree 267/2000.

Last update: May, 2022

In Italy several non-governmental organizations, belonging to the economic and social system, perform important functions in support of the cultural offer system, sometimes also influencing cultural policy.

For example, the 86 Italian Banking Foundations (“Fondazioni di origine bancaria”), operating for purposes of social utility and promotion of the economic development of the territory, make significant investments in the cultural sector. Although these Foundations are private law entities born in the early 90s from the transformation of the banking system, being non-profit organizations, they can sign agreements with public institutions, in order to support interventions for the enhancement of cultural heritage. However, it should be noted that since these entities are concentrated in the northern Regions, they contribute to increasing the territorial gap with the southern areas (see chapter 4.1.2 and 7.3).

Important subsidiarity functions in the management of the local cultural offer system and in supporting cultural innovation of the territories are carried out by third sector organizations. It is a heterogeneous galaxy of realities that in the last 30 years have seen their role progressively recognized and enabled by the institutions.

Already in the 70s and 80s, multipurpose cultural centres were funded by municipalities and run by cultural associations. ARCI (the Italian Cultural Recreational Association) is the largest and oldest Italian cultural and social promotion association, with hundreds of thousands of members and many associations and mutual aid societies throughout the country. It represents cinemas, theatres, music clubs, visual arts galleries, reading spaces, etc. and the promotion of cultural activities is the core of this associative project (see chapter 6.4).

The third sector reform process, launched in Italy in 2017 and still ongoing, has posed innovative and structural challenges to a large part of non for profit cultural organizations, but also to small and medium-sized enterprises operating in the cultural and creative sector. This reform has directly involved, for example, the phenomenon of “social enterprise”, which carries out one or more business activities on a permanent and main basis that are of general interest, non-profit making and pursue civic, solidarity and social utility purposes. The activities permitted by law include, among others, those relating to the “protection and valorisation of cultural heritage and the landscape”, the “organization and management of cultural, artistic or recreational activities of social interest” and the “organization and management of tourism activities of social, cultural or religious interest”. Social enterprises, in addition to a particularly favorable fiscal and tax treatment, can establish privileged relationships with public bodies, through forms of co-programming, co-planning and accreditation (see chapter 4.1.2).

Last update: May, 2022

At a horizontal level, inter-ministerial co-operation has been traditionally pursued by the Ministry of Culture also by means of memoranda of agreements signed, for instance, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the field of international cultural relations, with the Ministry of Education for arts training and education in schools, and with the Ministry of Justice for carrying out cultural activities in prisons aimed at the rehabilitation of offenders.

A key development in horizontal co-operation has been the participation, since 1999, of the Ministry of Culture in the Inter-ministerial Committee for Economic Planning (CIPE) of the Ministry for the Economy: a strategic committee, which is also responsible for the allocation of EU Structural Funds to the Regions in Southern Italy. Such areas have benefited from several million EUR in capital investments in the cultural field under the 2000-2006, 2007-2013 and 2014-2020 Plans, allocated to operational programmes managed by national and regional authorities. Their aim was to enhance cultural assets in the five Italian "convergence Regions” (Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Puglia, Sicilia), not only by boosting safeguarding, but also access, along with the connected economic activities dealing with the creation of new entrepreneurship, planning and capacity building.

As for vertical co-operation among government levels, common problems and quite frequent conflicts between the State and the Regions have often been dealt with in the framework of the State-Regions Conference - also acting as a sort of “clearing house” for any controversy – and, more rarely, by the Constitutional Court. Actually, official representation of regional interests in cultural, as in any other matter, is entrusted to the Conference, where the heads of the regional departments for culture regularly meet to discuss issues of common interest in two special coordination committees, the Interregional committee for cultural goods and the Interregional committee for the performing arts, also acting as lobbying organizations, pursuing institutional reforms towards a full implementation of a more federal governance structure in the cultural field.

Last update: May, 2022

As highlighted, in the mixed economy system of the Italian cultural policy model, the public sector historically is the primary funding source for cultural institutions in the field of heritage, museums, archives and libraries, as well as the performing arts. As previously pointed out, if on the one hand government action is concerned in the management of cultural institutions, on the other hand, the administrative model has traditionally been one of direct intervention of public administration by national ministries or regional, provincial and municipal ad hoc departments.

Last update: May, 2022

Table 1: Cultural institutions, by sector and domain

| Domain | Cultural institutions (subdomains) | Public sector | Private sector | Unspecified | |||

| Number (2019) | Trend last 5 years (In %) | Number (2019) | Trend last 5 years (In %) | Number (2019) | Trend last 5 years (In %) | ||

| Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage sites (recognised) * | 3.074 | -3.64% | 1.689 | -4.79% | ||

| Archaeological sites * | 292 | 12.31% | 28 | 55.56% | |||

| Museums | Museum institutions * | 2.386 | -7.34% | 1.446 | -8.42% | ||

| Archives | Archive institutions * | 101 | 0% | NA | |||

| Visual arts | Public art galleries / exhibition halls ^ | 761 °°° | NA | ||||

| Performing arts | Scenic and stable spaces for theatre ^ | 8.211 °°° | -47.61% | ||||

| Concert houses ^ | 4.853 °°° | -53.06% | |||||

| Theatre companies | NA | NA | |||||

| Dance and ballet companies | NA | NA | |||||

| Symphonic orchestras | 14 ° | 7.69% | |||||

| Libraries | Libraries * | 6.066 °°° | 3.13% | 1.393 °°° | NA | ||

| Audiovisual | Cinemas ^ | 5.325 °°° | 5.38% | ||||

| Broadcasting organisations * | 1463 | -5.43% | |||||

| Interdisciplinary | Socio-cultural centres / cultural houses | NA | NA | ||||

| Other (please explain) | Monuments * | 396 | 11.55% | 215 | 21.47% |

° Data relating to 2017; comparison with 2014

°°° Data relating to 2020; comparison with 2015

“NA”: no data available

The columns labeled “Unspecified” refer to domains for which it was not possible to distinguish between public and private sectors.

The percentage trend is calculated using the year 2014 as a reference.

As regards the data entered, it should be noted that:

- The item Cultural heritage - Cultural heritage sites includes the underlying items Archeological sites and Museums and also the item included in Other, i.e. “monuments and complexes”.

- The item Cultural heritage - Archeological sites includes “archaeological areas and parks”.

- The item Museums includes “museums and galleries”.

- The Archives are the “state archives”.

- The Visual arts item includes “exhibition spaces”. Data on Broadcasting organizations relates to companies that carry out “programming and broadcasting activities”, which is made up of the items “radio broadcasts” and “programming and television broadcasting activities”.

- The Concert houses item includes “spaces for concert activity”.

Last update: May, 2022

Since the end of the 90s, innovative legislation brought about substantial changes in the related cultural administration system. The main trend was “désétatisation”: i.e. gradually entrusting third sector status to public cultural institutions to grant them more autonomy and encouraging them towards public/private partnership. The logic behind these organizational changes was a) to pursue a more efficient management of these institutions, traditionally paralysed by red tape; b) to ease the burden they represent for the public purse by facilitating fundraising from the private sector.

The first quasi-independent (arm’s length) public institutions involved in this process have been:

- the fourteen main opera houses (“Enti autonomi lirici”) - including La Scala in Milan, the Rome Opera, La Fenice in Venice, the Maggio Fiorentino, the S. Carlo in Naples, etc., and the only national orchestra, the Accademia di S. Cecilia - transformed in 1996 into "Fondazioni liriche" (see chapter 3.3);

- La Biennale di Venezia, Triennale di Milano and La Quadriennale di Roma: public bodies organizing prestigious exhibitions and events in the domain of the visual and / or performing arts, all transformed into foundations facilitated by the public sector;

- the Centro sperimentale di cinematografia, composed of two separate entities: the Cineteca nazionale (the national film archive), and the Scuola nazionale di cinema.

The reform was deemed necessary for rationalizing the exceeding costs of such privileged institutions, amounting to as much as half of the total state expenditure for the performing arts and the film industry. Leg. Decrees 367/1996 and 134/1998 were thus aimed at transforming the opera houses into more flexible “lyric foundations” with a private status, possibly able to attract private capital through fiscal incentives. However, in the following years, a serious difficulty emerged in obtaining the required private support and further government measures were adopted to ensure the economic and financial sustainability of these entities (see chapter 3.3 and 4.2.3).

At the central level, it is also important to highlight the process of reorganization based on economic and managerial autonomy which has involved several major state sites since 2014. To date, there are 44 Museums, Monuments and Archaeological sites with special autonomy, coordinated by the DG of Museums (see chapter 3.1).

Following the reform process started towards the end of the 90s, the number of organizational changes that involved cultural public institutions has grown exponentially in the past twenty-five years. Significant cases of public-private partnership in the management of cultural institutions (theatres, auditoriums, exhibitions centres, museums, etc.) have been until now even more boldly experimented by local authorities through autonomous operated organizations (“gestioni autonome”). This process was initiated by Law 142/1990 on Local Autonomies and has been further encouraged by Decree 267/2000, singling out different innovative models for the operation of “public non-economic local services”.

Among the most frequently adopted models for cultural organizations have been foundations, institutions, associations, companies, and consortia. A significant number of entities mainly active in the management of theatres, museums and sites was, in particular, organized in the form of foundations. The reason for this model lies in a tendency of public administrations to consider foundations as flexible tools, particularly fit for privately pursuing public aims: hence the growing propensity to use them as new agents of policies, as well as to foster public-private partnership. Modernization in managerial procedures and techniques, increased capacity building, the fostering of innovative forms of public private partnership, are some of the ingredients of their growing success.

An important area of progressive reform also concerns partnerships between public cultural institutions and private profit and non-profit actors. Public-private partnerships in Italy have been mainly of a traditional type, with the private sector that intervenes through public tenders for the concession of services within public spaces (museums, archaeological sites, etc.). In recent years, actions taken have increasingly seen public actors (public bodies and universities) and private actors (associations, foundations, cooperatives) collaborate in the management of public cultural heritage. The third sector reform provides new forms of collaboration between third sector organizations and public administrations for the development of public-private partnerships (see chapter 1.2.5).

Furthermore, in terms of trends and strategies, it is necessary to refer to the impacts generated by the Covid-19 pandemic, starting from the first months of 2020, on the system of Italian cultural institutions, with the main support measures undertaken at the government level.

Obviously, the frame and the entire organization of heritage management at all levels has been hit with unpredictable violence by the pandemic. The business model of museums and monuments based not only on public funding, but also on a significant contribution of tickets sold, entered in a dramatic crisis after lockdowns and the adoption of extraordinary constraints reducing the audience capacity for pandemic risks prevention[1].

This unexpected situation pushed the Government and the Ministry of Culture to adopt, since the first months of the pandemic, exceptional measures aimed to sustain the crisis of a large number of institutions and to counter the negative effects of the emergency on the cultural and tourism sector (see chapter 3.1 and 7.1.3). Measures were extended and supplemented in 2021 due to the continuation of the pandemic crisis.

Adding to these challenges, in order to sustain the investments in protecting, restoring and enhancing the material and intangible heritage, the MiC established in 2020 a Cultural Fund, whose total endowment could be increased in partnership with private actors, through activities of micro-funding and crowdfunding. Finally, a significant amount of resources will be invested in the cultural sector starting from the 2021, thanks to the PNRR, the National Plan of Resilience and Resistance.

[1] Italian official statistics evaluate a loss of approx. 78 millions Euros in just three months from March to May 2020, due to the lockdown, only for the State Museum.

Last update: May, 2022

The actors responsible for international cultural cooperation are:

1) MAECI - Ministry for Foreign Affair and International Cooperation.

Law 125/2014 is aimed at modernizing Italian cooperation activities through the construction of four pillars: firstly, the “coherence of government policies” guaranteed by the Inter-ministerial Committee for Cooperation and Development (CICS); secondly, the institution of a Vice-Minister for Cooperation; thirdly, the definition of “an Italian cooperation system” that oversees the involvement and interaction of new players from the non-profit sector and the private one; and fourthly, the Italian Agency for Cooperation and Development (AICS), which began operating in 2016 and acts as a hub connecting national and local institutions, plus non-profit and profit-making organizations.

Cultural cooperation activities are carried out by MAECI’s main institutional actor: the Directorate Central for Cultural and Economic Promotion and Innovation, which includes Office VI - Multilateral cultural cooperation, archaeological missions; Office VII - Promotion of the Italian language and publications, internationalization of universities, fellowships; and Office VIII - Cultural promotion and the Italian Cultural Institutes.

Bilateral cooperation is also carried out by means of bilateral cultural agreements with other countries, dealing with a whole range of activities: exchanges of scholars, artists, performances, archaeological missions, and, in particular, film. Among the most recently established cultural bilateral agreements are those with Brazil, China, Iraq, Uruguay and Vietnam. Regarding multilateral cultural co-operation, the Directorate Central's main role relates to UNESCO and ICCROM, where the focus of Italian activities has mostly been on heritage (see chapter 1.4.2).

The main problem of MAECI’s several administrative units in charge of the promotion of Italian culture abroad have to face deals with the progressive decrease in their already inadequate financial resources. Financial data only dealing with its cultural activities are not made available by the Ministry and this prevents reliable comparisons with other countries on state expenditure for international cultural cooperation.

2) MiC - Ministry of Culture.

Its strengthened international role should be also ascribed to the growing relevance in cultural cooperation matters of the Council of the Cultural Ministers of the Union, as well as to the enhancement of Italy’s leadership in advising and technically and financially supporting the developing countries’ heritage policies. MiC has no specific DG in charge of foreign relations, which are shared instead among the cabinet's Diplomatic Advisor and a Unit for International Relations supervised by the Secretary General, which includes Service II – UNESCO Office and Service III – International Relations.

In 2015 the International School of Cultural Heritage (“Fondazione Scuola dei beni e delle attività culturali”) was established (Law 22 February 2015 n. 11): it is a Foundation aimed at providing training, research and advanced studies as part of the mission of MiC, which is its founding partner. Gathering Italian and foreign professionals involved in managing cultural assets, the International School of Cultural Heritage programme is an initiative of professional development through the sharing of knowledge, experiences, methods, and tools in a sort of permanent workshop. Participants are selected by the government of the foreign countries. Each edition of the programme circumscribes a geographical area of origin of participants, and a thematic field among the wide sphere of cultural heritage. In the 2019-2020 edition, participants were invited from Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Tunisia, Turkey and Ethiopia as an associated country.

In 2019 the Directorate General for Education and Research was set up within the MIC (DPCM 2 December 2019 n. 169): it has the aim of promoting knowledge of cultural heritage and its social and civic functions at local, national and international level. It promotes a wider participation in European and international funded projects in co-operation with public and private European and international organisations. It cooperates with the Italian Cultural Institutes and it has coordinated the international project “Training Projects”, aimed at providing foreign countries with a training offer on different aspects of cultural heritage management, research and preservation. It also coordinates the pilot project co-funded by MAECI and addressed to Caribbean countries.

In 2016 the Ministry of Culture Franceschini announced the creation of a G7 for Culture. In March 2017 the Ministers of Culture of the seven countries met in Florence for the first G7 of culture to discuss the theme of “culture as an instrument of dialogue between peoples”.

3) Regional and local level

Most of the main cities have become important actors for international cultural exchanges, often in the framework of “twinning cities” bilateral agreements. Moreover, Creative Europe and other EU cultural programmes – along with programmes by the CoE – have acted as effective catalysts for regional and local international cultural cooperation.

Last update: May, 2022

As for the EU, Italy has always been at the forefront in the cultural field. Mrs. Silvia Costa supported the European Year of Cultural Heritage in 2018 and the launch of the I-Portunus Programme, aimed at promoting the mobility of artists. Mrs. S. Costa and Mr. M. Smeriglio, previous and current Rapporteurs for the Creative Europe Programme, supported the boosting of the budget of the programme 2021-2027.

Regarding the ECOC Programme, as a follow up of the competition for the Italian title won by Matera in 2019, MIC launched the Italian Capital of Culture. Mantova for 2016, Pistoia for 2017, Palermo for 2018 and Parma for 2020-2021 have already been awarded the title.

Italy is active in many cultural programmes carried out by the CoE (such as the Audiovisual Observatory, Eurimages, Phoenician Routes, Via Francigena).

In 2020 (Law 133/2020) the Parliament ratified the CoE’s Faro Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (2005), an important step-forward in the reflection on the role of citizens and communities in deciding and managing the cultural environment. As for UNESCO, MAECI and MiC are jointly responsible for monitoring the UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and of the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. As far as the latter is concerned, in 2020 the third quadrennial report was submitted[1]: it includes, for the first time, a specific focus on the role of the private sector in the implementation of the Convention.

[1] https://en.unesco.org/creativity/governance/periodic-reports/submission/3896

Last update: May, 2022

The projects of professional international cooperation in the arts and culture in which Italy has engaged are countless, and a comprehensive picture cannot be drawn, given the fragmentation of the actors involved. This chapter focuses on a few of the many significant international projects in which different public and private institutions/organizations are involved.

There is a number of on-going projects which have a consolidated history of partnership among European cultural institutions and guarantee a strong level of continuity, such as:

- Michael-Multilingual Inventory for Heritage in Europe started in 2004 by MIC-Ministry of Culture in partnership with the French Ministry for Culture and the UK Museums, Libraries and Archives Council, with the support of the EU Commission in the framework of the Programme e-TEN (Electronic Trans-European Networks). Its aim is the creation of a Trans-European Portal for on-line multilingual access to the digital cultural contents through the adoption of common standards;

- Europeana, a cultural portal funded by the Horizon2020 programme, giving access to 30 million pieces of data provided for by cultural institutions (1.3 million by Italian institutions). It is important to underline the focus it has on digital tools and developments;

- Ecole des Maitres is an innovative multi-annual educational and artistic project started in 1990 and aimed at connecting young chosen professional European stakeholders in the field of the performing arts. It has been supported by the ministries for culture of various countries and has often benefited from the financial support of the EU.

Other European projects, led by Italian organisations of the third sector, are more recent but present as well a feature of continuity and strong partnership among the public and private sectors. Among them, the following are worth mentioning:

- Fabulamundi Playwriting Europe is a project involving theatres, festivals and cultural organisations from different EU Countries. The network – which has been funded three times by the Creative Europe Programme – aims to support and promote contemporary playwriting across Europe;

- Adeste + is a large-scale European cooperation project co-funded twice by the Creative Europe project aimed at expanding cultural participation through capacity building processes;

- BeSpectatctive! is a large-scale European cooperation project – co-funded twice by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union – which operates in the performing arts through artistic productions and participatory practices aimed at involving the citizens and spectators in creative and organisational processes.

A very recent one is CHARTER, an Erasmus+ project funded in 2020 (starting date 2021). CHARTER aims toclarify occupational roles and activities and create the tools for an integrated, responsive education system; identify curricula and learning outcomes over a sample group in order to equip education and training to respond to current and future cultural heritage skills needs; and to put a structure on cultural heritage as an economically active sector. CHARTER reunites leading academic and training organizations and policy stakeholders in the European cultural heritage sector, which includes the Fondazione Scuola dei beni e delle attività culturali, supported by MiC.