1. Cultural policy system

Serbia

Last update: September, 2018

It is a truism that a nation's culture cannot be divorced from its social, economic and political circumstances and, in all these areas, Serbia has continued to face severe difficulties since the Democratic Opposition overthrew the Milosevic regime in October 2000. According to a government report, "Serbia emerged from the ashes with the heritage of a dissolved Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) and ten years of despotic and erratic rule, an economy in shambles and a legal and physical infrastructure badly distorted through the neglect and abuse of power."

The Belgrade Agreement of 2002 established the Federal State of Serbia-Montenegro, which was legally made up of two separate republics: the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Montenegro, each with its own ministry for culture. Informally, the Republic of Serbia included two autonomous provinces, Vojvodina (northern part of Serbia) and Kosovo; the latter, however, officially remains under the control of a United Nations administration and therefore the Serbian government has no legal influence in Kosovo. The province of Vojvodina has its own Secretariat for Culture and Public Information. The Belgrade Agreement stopped being relevant after the Referendum on 21 May 2006, when Montenegro became an independent nation. This paradoxically meant that, without a stated intention, Serbia also became an independent nation.

Despite the devastation of the nineties, and the difficulties of the present decade, many of the surviving strengths of Serbian cultural life can be seen to be derived from a long tradition of cultural discourse shaping national identity. At the level of infrastructure and management, one can look back to the relative certainties of life under the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia, in which decentralisation and institutional self-government were key characteristics of cultural policy as long ago as the 1960s. These traditional practices are still applicable today and are currently being adapted in response to the new social, economic and political conditions.

The development of cultural policy in Serbia, over the past fifty years, can be examined within six main phases of political change:

Social Realism and a Repressive Cultural Model (1945 – 1953): The first phase can be characterised by social realism copied from Stalin's model of culture in the former USSR. The function of culture, in an ideological sense, was utilitarian and did not encourage the idea of culture as a field for individual freedom of any sort. Luckily, this phase was brief and was followed by a period of progressive cultural action.

Democracy in Culture (1953 – 1974): Within the second phase, two parallel cultural developments can be identified; one was still under strong state and ideological control, while the other, which was more creative and vivid, slowly gained artistic freedom. By the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s, many new institutions and prestigious international festivals for different art forms had been established. A large network of municipal cultural institutions, such as houses of culture, libraries and cinemas was also created. At the same time, many individual artists were sanctioned and their works (films, theatre plays and productions, books, etc.) were banned. This was not an officially proclaimed policy but was exercised through political and ideological pressure.

Decentralisation and Self-Governance (1974 – 1989): This third phase is particularly known for the specific policy initiatives to decentralise culture throughout the former Yugoslavia. Serbia had some additional particularities concerning its multi-ethnic and multi-cultural character. Two autonomous provinces (Vojvodina and Kosovo) were given full competence over cultural policy as a result of their multi-ethnic and cultural structure. The entire cultural system was transformed during this period. Self-governing communities of interest were introduced and "free labour exchanges" facilitated closer links among cultural institutions and local economies through, for example, theatre communities, private galleries, etc. In the mid-1980s, a strong nationalistic movement emerged among official and unofficial political and cultural institutions, which was especially stimulated by the liberalisation of the media.

Culture of Nationalism (1990 – 2000): Serbia and Montenegro was lacking a general concept or strategy for culture as well as a clear definition of cultural policy. This ambiguity, therefore, marginalised culture as a creative impulse and process in the modernisation of society and emphasised its role as a "keeper" and promoter of national identity. Self-government was abolished as a system, and cultural institutions were returned to state / municipal authority, nominating directors and controlling their activities. The role and contribution of leading cultural NGOs had been vitally important in Serbia. They first became a distinct feature of opposition to the official culture of nationalism and state control in Serbia during the Milosevic years. In fact, it has been claimed that as much as 50% of the resistance to the Milosevic regime, during the 1990s, was manifested through culture and the active struggle on the part of NGOs, independent publishers and artists for a different way of life. This struggle was spread throughout the country. Their actions received significant material assistance from the international community and notably from the Soros Foundation via its Open Society Fund, Serbia.

Culture in Transformation (2001 - 2011): This period is characterized by a series of attempts to set cultural policy on a strategic, democratic and well-planned basis, while at the same time there have been many political turbulences, changes of Ministers and transitional fatigue which have all together undermined and bracketed many of the attempts. Despite the attempts to introduce new order, the policy of this period has been incoherent and chaotic, somewhat due to the fact that the Ministry of Culture has changed its leadership 5 times in 11 years – noticeable all Ministers and main advisors have been male.

A special accent was placed on reforms of the main national cultural institutions and the public sector in general, demanding the introduction of new managerial and marketing techniques. The first evaluation of national cultural policy within the Council of Europe programme had been completed and was approved in November 2002 while the second one has been completed in April 2015.

Taking into account more than 10 years of devastation, extreme centralisation, étatisation and manipulation, the necessary priorities for all levels of public policy-making were: decentralisation and desétatisation of culture; establishing an environment to stimulate the market orientation of cultural institutions and their efficient and effective work; setting a new legal framework for culture (harmonization with European standards); multiculturalism as one of the key characteristics of both Serbian and Montenegrin society and culture; re-establishing regional co-operation and ties; and active co-operation in pre-accession processes to the CoE, EU and WTO.

The cultural policy debate has been fading and many of the attempted changes have proven to be short lived. One of the most emblematic signs of such inability to run a coherent and strategic policy is the case of two of the biggest national museums (The National Museum and Museum of Contemporary Arts) which were in the state of refurbishment for more than a decade because of the lack of leadership and many scandals, which created a big gap between audiences and these institutions. In the same token, the National Cultural Strategy envisioned by the new Law on Culture from 2007 to be adopted in the shortest time possible, has not been adopted until 2018.

Still, a few interesting initiatives can be identified. In 2007, a new Ministry of Culture started to work on new priorities and strategies. Many working groups were created, to establish new laws (General Law on Culture, heritage protection, etc.), or to define new concrete programmes and strategies (digitalisation, decentralisation, cultural research development, etc.) or to introduce certain topics for public debate (politics of memory and remembrance, culture for children, intercultural dialogue, etc.). Public debates were held on drafts of new legislation, with the involvement of the Minister, representatives of the Ministry and experts (mostly cultural professionals), in the first six months of the new government. However, after one year, another new government had been created and a new Minister for Culture was appointed in July 2008.

While open competitions to fund cultural projects have been in operation since 2000, decided by commissions, the first competition for commission members was only launched in September 2006, changing the policy of nominations to the commissions to a more transparent procedure. However, this practice has had different levels of transparency and autonomy depending on the Minister or other external pressures.

Back to national unity (2012-2018): In 2012,a new Minister of Culture has been appointed, for the first time from the Serbian Progressive Party, followed by two other Ministers appointed by the same political option. There are several trends noticeable in this period. Short Ministerial appointments continued, with every Minister trying to leave a strong personal mark (still all male). The dialogue with the independent scene and the private sector, somewhat established in the previous period, was systematically and occasionally undermined. Most notably, in 2013 Minister cancelled a cooperation agreement with the Association Independent Culture Scene of Serbia (ICCS). The ministerial budget has remained very low (0.64% of government budget) despite promises. Finally, it can be noted that the focus was mainly on the "renationalisation" of Serbian institutions on material and immaterial heritage preservation and reorienting institutional cultural sector towards the strengthening of national cultural unity. In this respect, a new policy of memory and remembrance (focusing on the Balkan wars & World War One – wars in which Serbia was a winning party) complement a similar cultural diplomacy policy focusing on Slavic countries (a first agreement on cooperation was signed with Belorussia, in Minsk on 29 October 2012); a new draft of Cultural Strategy (2017) focusing on integration and strengthening “Serbian National Space”; increased support for Serbian Orthodox Church; linguistic measures that promote Cyrillic script and discourage the use of other scripts. Since, 2016. personal changes in public cultural institutions has been evident (at national as well local level). All most cultural institutions at national level have changed members of executive boards as well directors. In many cases, strong and professional cultural workers were changed with person outside cultural field and/or without professional integrity and achievements. Strong pressures on open mind cultural directors/professionals are evident especially on the local level.

Still, in this period, two of the biggest national museums were finally opened, Novi Sad has gained a title of European Capital of Culture and New Strategy for Cultural Development from 2017 to 2027 has been drafted.

Main features of the current cultural policy model

The Serbian model of government is different from the models adopted by the different countries of Eastern Europe due to its legacy of self-government. In this system, there was relative freedom for art production and the majority of cultural institutions were owned by the cities. Since 1980, artists have been given the possibility to organise themselves in groups and to produce and circulate their own work.

It should be taken into account that the present system of institutions, arts groups and even artists had been created and developed throughout the ex-Yugoslavian territory, especially in the City of Belgrade. With the collapse of the ex-Yugoslavia, cultural productions (e.g. films, books, journals, festivals, etc.) lost their audiences, readers and markets. The cultural infrastructure that followed was, hence, too large to survive and demanded (in %) more and more public funds. This was one of the main reasons why there were few protests when the government resumed control of socially owned (self-governed) cultural institutions during the 1990s. Instead, it was considered a step to at least guarantee the survival of existing cultural institutions.

The current cultural policy model has changed slightly: key competence for cultural policy-making and funding is the responsibility of the Ministry of Culture and new procedures were introduced in Serbia in 2001. Last changes in funding procedures were adopted in 2016.

The majority of the Ministry’s budget (69%) goes to supporting cultural institutions (see Table 1).

Table 1 – Allocated budget for cultural activities 2015 – 2018

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall budget for cultural activities (din) | 7,307,547,000 | 6.488.947.000 | 7,883,745,000 | 7.493.969.000 |

| Overall budget for cultural activities (%) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Overall budget for cultural activities (EUR) | 61,254,000 € | 52,928.000 € | 63,733,000 € | 63.508,000 € |

| National cultural institutions (din) | 4,196,390.000 | 4,209,121,000 | 4,636,358,000 | 5,188,636,000 |

| National cultural institutions (%) | 57.43% | 64.87% | 58.81% | 69.24% |

| National cultural institutions (EUR) | 35,175,000 € | 34,332,000 € | 37,481,000 € | 43,971,000 € |

| Capital projects (din) | 1,623,348,000 | 800,000,000 | 1,526,793,000 | 314,909.000 |

| Capital projects (%) | 22.21% | 12.33% | 19.37% | 4.20% |

| Capital projects (EUR) | 13,607,000 € | 6,525,000 € | 12,343,000 € | 2,669,000 € |

| Protection of cultural heritage (din) | 582,000,000 | 521,500,000 | 631,500,000 | 789.810.000 |

| Protection of cultural heritage (%) | 7.96% | 8.04% | 8.01% | 10.54% |

| Protection of cultural heritage (EUR) | 4,879,000 € | 4,254,000 € | 5.105.000 € | 6.693.000 € |

| Contemporary artistic production (din) | 496,986,000 | 537,000,000 | 532,000,000 | 603.300.000 |

| Contemporary artistic production (%) | 6.80% | 8.28% | 6.75% | 8.05% |

| Contemporary artistic production (EUR) | 4,166,000 € | 4,380,000 € | 4.301.000 € | 5.113.000 € |

| International cultural cooperation (din) | 155,537,000 | 178.926.000 | 314,694,000 | 378.349.000 |

| International cultural cooperation (%) | 2.13% | 2.76% | 3.99% | 5.05% |

| International cultural cooperation (EUR) | 1,304,000 € | 1.460.000 € | 2.544.000 € | 3.206.000 € |

| Acknowledgments for cultural contr. (din) | 253,286,000 | 242.400.000 | 242.400.000 | 218.965.000 |

| Acknowledgments for cultural contr. (%) | 3.47% | 3.74% | 3.07% | 2.92% |

| Acknowledgments for cultural contr. (EUR) | 2,123,000 € | 1.977.000 € | 1.959.000 € | 1.856.000 € |

Source: Cvetičanin (2018)

There are several key calls for project granting: arts and contemporary creativity; media and public information; and cultural heritage. In 2018, in the area of arts, the Ministry has allocated around 3 million EUR to projects in the following 14 areas:

- literary art (production and translation);

- music production (creation, production, interpretation);

- visual and applied arts, design and architecture;

- theatrical arts (creation, production, interpretation);

- digital arts and multimedia;

- performing arts (ballet, folk dance and contemporary dance);

- cinematography and audio-visual creation (film production, workshops and art colonies);

- research and educational projects;

- autochthonous creativity (folklore) and amateur arts;

- cultural activities of national minorities;

- cultural activities of Serbs who live abroad;

- cultural activities for persons with special needs;

- cultural activities of marginalised groups;

- cultural activities for children and youth.

In the field of cultural heritage, the Ministry has allocated 274 million dinars in 2014, and selected 465 projects to be funded. Projects were grouped in the following seven areas, aiming to discovering, collecting, research, documenting, valorising, protection, preservation, interpretation, presentation, management and use of (1) immovable cultural heritage; (2) archaeological heritage; (3) museum heritage; (4) archive materials; (5) intangible cultural heritage; (6) rare and old library materials; (7) as well as for library and information activities.

Most of the money on these calls go to cultural institutions, while civil society organisations received 1.310.000 EUR. We can see from this that the overwhelming majority of the Ministry’s budget is devoted to supporting public cultural infrastructure. When it comes to different fields, most funds were awarded to film (21%), music (20%), theatre (18%) and visual arts (14%), while dance, youth culture, culture for people with special needs and other received less than 10%.

In the field of cultural heritage, the Ministry has allocated supports to the following seven areas, aiming to discovering, collecting, research, documenting, valorising, protection, preservation, interpretation, presentation, management and use of (1) immovable cultural heritage; (2) archaeological heritage; (3) museum heritage; (4) archive materials; (5) intangible cultural heritage; (6) rare and old library materials; (7) as well as for library and information activities. Since 2010 open competition in cultural heritage has been introduced with a yearly budget between 2-2,5 million EUR.

Apart from these key calls, there are also granting schemes for international projects (though mainly translations of Serbian authors and Serbian cultural organisations abroad), buyout for books and visual artworks (the latter was reopened this year after long period, which was warmly welcomed by numerous actors), digitalization of cultural heritage, reconstruction of municipality cultural infrastructure and improving access to cultural contents (programme “Cultural Cities in Focus”). Finally, with the signing of the Creative Europe programme, the Ministry also opened call for co-financing projects that were selected in the programme (up to 30% of local budget for applicant organisations and up to 50% for leading organisations). This support is also viable for other international cultural programmes of UNESCO, EU Council of Europe and other.

The majority of projects take place in Belgrade (43.38%), followed by Novi Sad (10.30%), and 46.32% of projects take place in other cities and municipalities (Požarevac, Čačak, Subotica, Požega, Ruma, Užice, Kragujevac, Leskovac, Pančevo and Omoljica, Gornji Milanovac, Bajina Bašta, Vranje, Gračanica, Smederevo, Bačka Topola, Niš, Kučevo). (Source: Cultural diplomacy: Arts, Festivals and Geopolitics, pp. 337-9.)

Decision-making processes for these open competitions had been transferred to independent commissions. That is why the current cultural policy model is described as a combined etatist-democratic model. There are many different commissions and juries for different competitions in the field of culture and media. Since 2014, the granting mechanism was slightly improved, most of which in 2018 when the Ministry started publishing Jury members’ identities, public argumentation of awarded and refused projects and granted sums. But still, this transparency can be marked as a “formal transparency” obligated by the Law on culture, with almost “copy paste” comments and arguments on projects.

It is important to note that open calls, despite their high value as one of the very few funds for non-institutional actors, have several flaws. First of all, very little amount of funds is distributed through calls (slightly more than 4 per cent of Ministry budget). In the scenario in which cultural organisations would have diversified income streams, this would be fine. However, many organisations are highly dependent upon Ministry. As a result of the vast number of applications (in 2018 it was about 3500 projects), most organisations receive as little as 3000 or 4000 euros. Even with such a small amount, only about half of the projects that apply get selected. Second, calls are vague and unspecified, regarding the amount of funds, goals of the projects or needs of beneficiaries. With such diverse and unfocused approach, it is hard to see how these calls might have any effect on solving numerous problems of cultural sector (lack of skills, lack of audience development, brain drain, etc.). Third, with a sectorial approach (visual arts, music, arts etc.) cooperation between sectors is discouraged and many organisations face problems when developing multidisciplinary projects. Fourth, even the approved project finally might not be funded specially in the case if organisation got several grants form different budget lines. Finally, approved projects are almost never properly evaluated and there is no report made by the Ministry to date that has analysed any kind of impact of the calls.

The National Council for Culture was set up on 25 May 2011 and it brought a kind of optimism in the cultural field, seen as an opportunity for a creation of a more autonomous artist-led cultural policy. In 2010, the Council prepared a version of the National Strategy, however, due to the changes of Ministers, this document never really reached public debate.. Over the years, the relation between the Minister and the Council became tense, the finances for the Council were cancelled, and although the actual Law still foresees a Council, since 2015 it is not functioning – i.e. it has lost its meaning due to the lack of political will to support the work of such arm’s length body. At the beginning of 2016, mandates of the Council members expired and the process of selecting new members is marked by controversial issues and disapprovals of cultural professionals.

Cultural policy objectives

In 2017, the new Ministry of Culture has published a Draft of the Strategy of Cultural Development 2017-2027 - after several decades of lacking such a document - in which many elements of the cultural policy have been made explicit. Although it is largely incoherent due to multiple author teams and many versions upon which it was built, it presents several clear objectives and trajectories of cultural policy.

First, the Ministry is devoted to the development of a “institutional cultural system”, by which is meant the growth, systematization and development of cultural policy and the functioning of public cultural institutions. Among the main measures are: (1) new legislation involving new niche laws (on cultural heritage, archaeology, museums, cinematography, theatre…) as well as amending existing laws which have a great impact on artistic and cultural work (e.g. law on public procurement, law on income taxation, etc.); (2) increased financing both in operational sense (increase from 0,68 to 1,5% is projected by 2026) and in capital investments (building of numerous new museums, theatres and libraries in cities outside Belgrade, new depots for National Library and National archive, etc.); and fostering of public-private partnership and entrepreneurship in culture, as well as increased support for local institutions and organisation to participate in international calls for actions and projects.

The second priority is “responsible human resources development and management in culture” and is aimed at improving the knowledge of local cultural workers, mainly in cultural institutions. Main objectives include permanent education of staff; increased collaboration with universities; increased competition among institutions and adequate awarding system; and informational database system (e-kultura.net) devoted to digitalization of culture and central storing of cultural development related data.

The third and fourth priorities deal with cultural participation, one with equality of participation, the other with the development of cultural needs. They mostly follow EU trends in increasing cultural participation and involve the decentralization of cultural offering, an increased role of local municipalities in providing cultural content and the support for collaboration of cultural institutions and media outlets and educational institutions.

The fifth priority, named “Culture of mutual understanding” follows explicitly the The UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions and includes strengthening organisational capacities for dialogue, support for minority cultures and projects which aim at establishing and promoting dialogue between cultures.

However, the following sixth and seventh priorities are somewhat contradictory to the fifth one. In Promoting Serbian language and Cyrillic script, the legislator is foreseeing all sorts of measures to change the use of language and script in the public realm which is mostly Latin script and increasingly English language. Measures involve: decreased taxation of cultural goods and products in Cyrillic script, suggesting to all television companies to have 50% of subtitles in Cyrillic script, SMS texting in Cyrillic, and obliging all cultural events supported by the Ministry to have logo in Cyrillic script. When it comes to the integration of the “Serbian Cultural Space” (a term first occurring in the Strategy), the Ministry is recognizing the existence of cross-border and cross-continental cultural space tightly linked to Serbian nation and ethnicity, mainly involving Serbian diaspora across the world. Foreign cultural centres are planned to be opened (only one existing so far in Paris); support is aimed at university chairs and departments studying Serbian language; cultural monuments in other countries related to Serbian individuals and culture are to be protected; and cultural activities by Serbs in Serbian language abroad are to be supported.

In relation to the previous policy objectives, much has remained the same: accordance with European values (multiculturalism, diversity, cultural democracy and participation), strengthening the public institutional system, preservation of national heritage, decentralization, etc. Some notions, however, have been added or expressed with more fervor, mostly the ones related to Serbian national identity and unity.

After the Draft of the Strategy was announced (still not voted by the Parliament), there has been a growing fear of conservatism and nationalism on the one hand, while on the other the document seems an overly optimistic and promising collection of desires, often in tension with one another. Especially problematic are the plans of the increased cultural budget which lies at the basis of the document. Since it is still in the making, one cannot judge if these priorities will also be actually practiced, however some activities (discussed later) show that the Ministry is willing to pursue the trends set by the document and discussed so far.

Last update: September, 2018

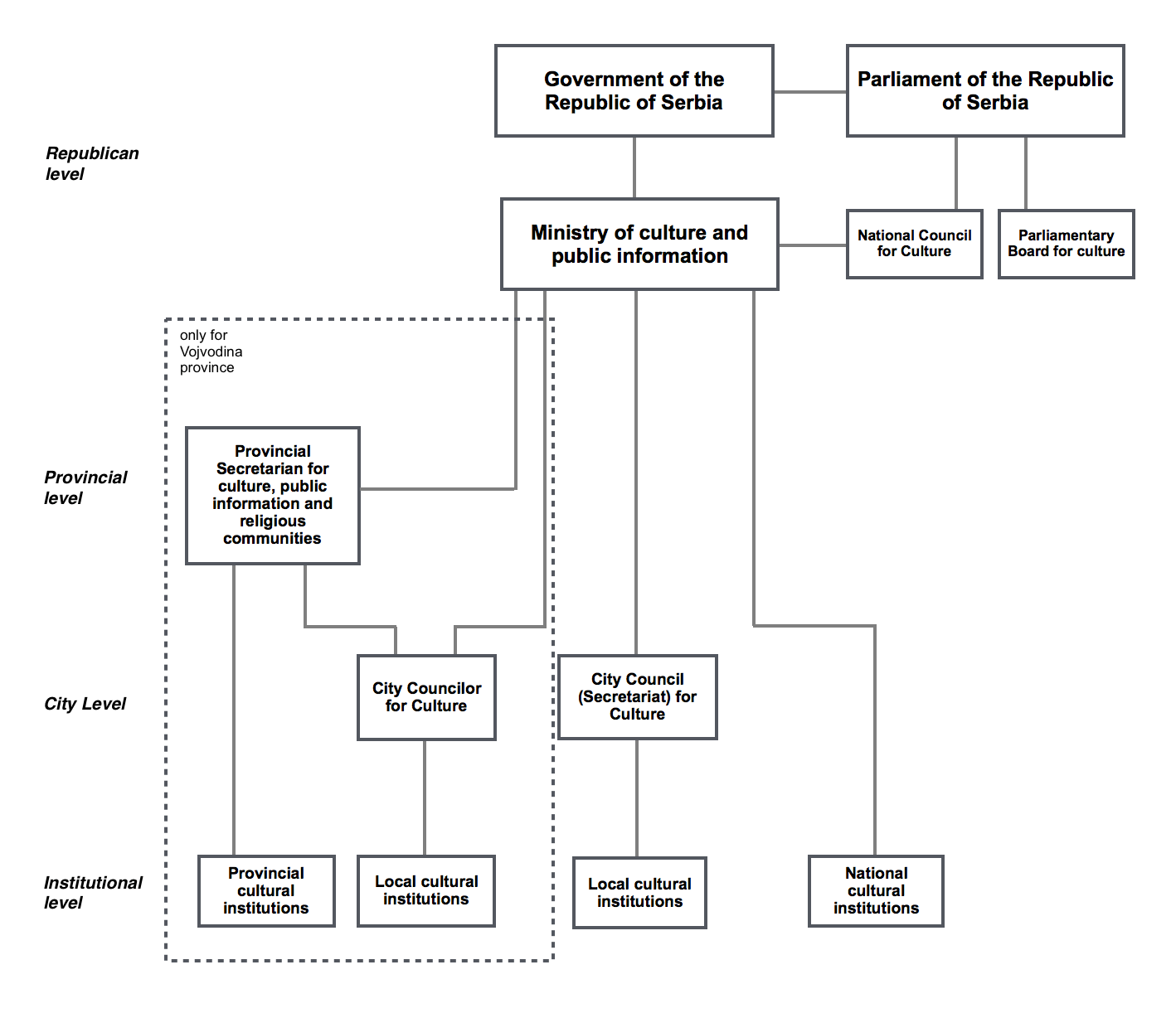

Organisation of cultural policy in Serbia is quite straightforward and linear with the Ministry of Culture as the main actor. The Ministry proposes Laws and strategies, it is in charge of the largest budget, and has the authority over all other levels of public, institutional policy making. There are however many cases – such as the appointment of the directors of public institutions, awarding protection levels for sites and monuments, etc. – in which the Government is officially in charge of decision making. This has been specifically problematic when the Minister came from a smaller coalition partner, which meant that his voice (for over 20 years all Ministers were male) was marginal in the Governmental meetings.

The Law on Culture also foresees the role of the Parliament and the National Council for Culture envisaged as a non-partisan body of experts and artists in consulting, critiquing or advising the Ministry and the Government on cultural affairs. However, seen as a potential source of dissent, this body has been deprived of finances and membership and it became inefficient very soon after its foundation.

Another formal adjustment that aimed at providing autonomy from the Ministry is the Provincial Secretariat for Culture of Vojvodina Province. As a culturally distinct area, with pronounced multicultural traditions and everyday life, the Provincial Government of Vojvodina has been granted some space to run its own cultural policy. The Provincial Secretariat for Culture has been traditionally focused on supporting national minorities and the promotion of multiculturalism and tolerance. With such niche orientation, it has not played a more pronounced role in the overall structure of policy making.

Scheme of cultural policy in Serbia

It is important to note that this scheme is a simplified representation of the actual system, which is more complex, incoherent and dynamic than any scheme may show. There are some elements of the system in some areas that do not function in the represented fashion. For example, when it comes to the protection of cultural heritage, local institutes that exist in major cities (Belgrade, Novi Sad, Niš, Subotica, Zrenjanin, Kraljevo, Valjevo, Kragujevac, Sremska Mitrovica, Pančevo, Smederevo) cover an area wider than the city they are founded and funded by, and they all report directly to the Republic Institute in Belgrade.

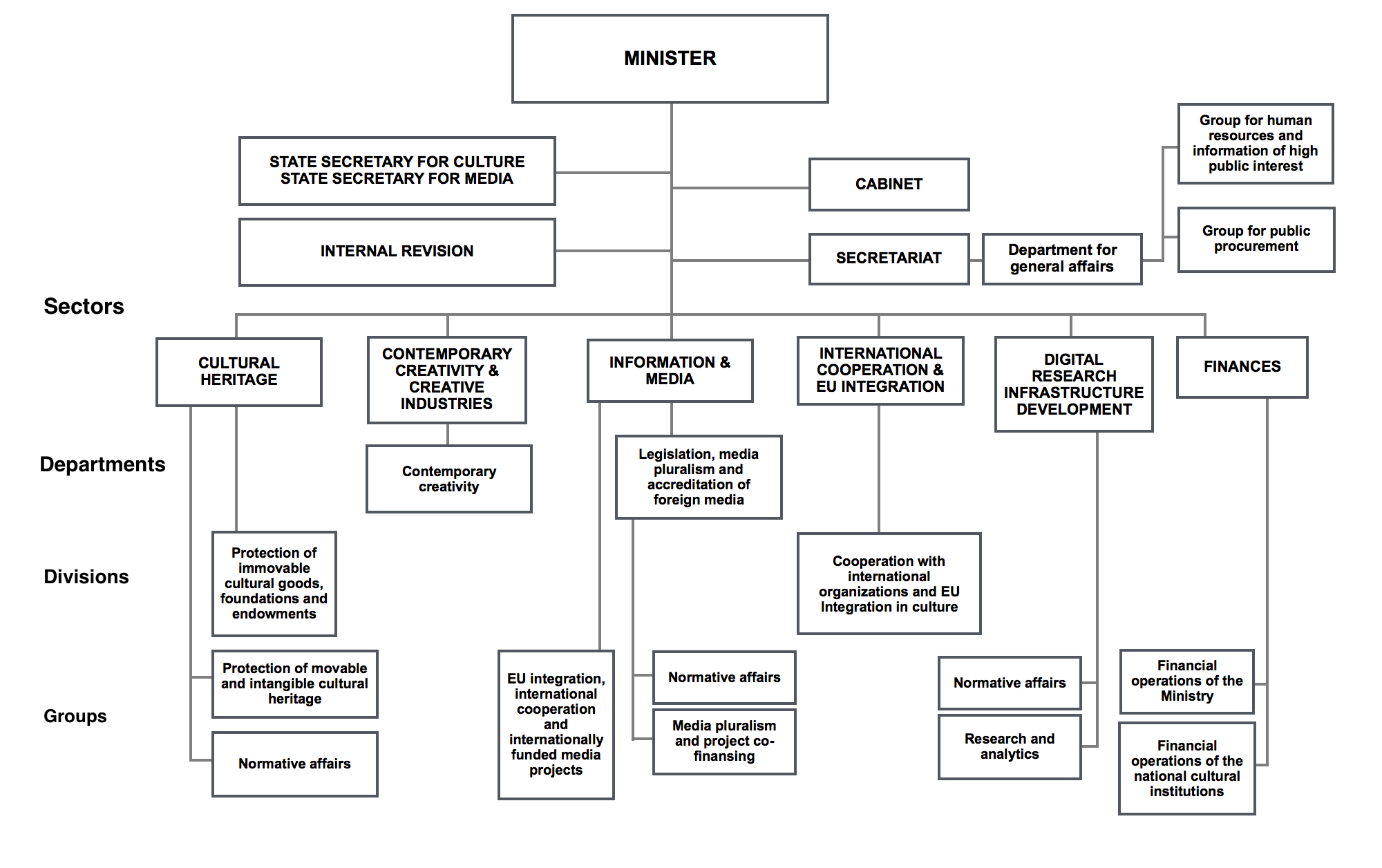

Ministry of Culture and Information

In 2010, The Cultural Contact Point was integrated within the Ministry, temporarily attached to the Media department, while in November 2012 the CCP was moved out of the Ministry in order to leave more space for the new cultural administration. With the new Creative Europe programme in 2014, the Ministry dissolved the CCP and opened the Creative Europe desk, inside the Ministry with existing personnel, further incorporating the work of the desk.

The current organisation of the Ministry of Culture and Information (set up in 2016) is as follows:

Organigram of Ministry of Culture and Information

Last update: September, 2018

The Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Serbia has overall responsibility for culture, which it partly shares with the Secretariat for Culture in the autonomous province of Vojvodina. This sharing of responsibility was carried out on the basis of the "Omnibus Law" passed in February 2002 and in line with the general policy of decentralisation.

The Ministry of Education and Science is responsible for arts education, arts management training, youth and student cultural activities and institutions, while the Science department is financing research in the field of humanities and social sciences.

Ministry of Culture and Information (later in the text Ministry of Culture) is the main body responsible for: policies and strategies for cultural development, support for 40 cultural institutions of national importance, legal issues in the field of culture, protection of the cultural heritage, and regulating and preparation of the laws relevant to the media space.

National Council for Culture members are selected from respected artists and cultural managers for a five-year period. The Council has 19 members, confirmed by the National Assembly: 4 are suggested by government, 4 from public cultural institutions covering dominant areas: heritage, performing arts, librarianship and cultural development; 4 members representing art associations (literature and translation; visual arts; music; drama); 1 member representing other cultural associations; 2 members from the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2 members from the University of Arts and 2 members suggested by councils of national minorities.

Last update: September, 2018

Provincial Secretariat for Culture and Public Information of Vojvodina is responsible for specific issues of cultural policy in its territory due to the special needs and multi-ethnic structure of this province. It is responsible for the major provincial cultural institutions since the Omnibus Law of 2002. The Law on Culture (2010) had confirmed its authority and since 2011 the complete financing for culture comes from the budget of Vojvodina (previously, the Ministry of Culture every year had transferred money to the Provincial Secretariat).

In July 2012, the Constitutional Court produced questions on 22 paragraphs about the responsibilities of the region of Vojvodina, like the use of the word CAPITAL city for Novi Sad, or possibility to open up its delegation in Brussels. Recently, in October 2012, several paragraphs in Law about the transfer of responsibilities to the region of Vojvodina were also put in question (abolished), regarding the use of the official language on the territory of Vojvodina and especially paragraph 64 which regulates research and science policy. Denying those rights, the existence of the Academy of Arts and Sciences of Vojvodina is put into question, as well as co-financing of the research projects. If the decision of Constitutional court would be consequently implemented, even the existence of University of Novi Sad as a research institution could be put into question, as its founder is the Regional Assembly.

Article 64 research projects linked to minority issues (the key organisation is the department for minority languages of Novi Sad university) are also endangered, but now areas where the Province could have authority, such as culture and agriculture, would incorporate research activities in those domains, so at least research in the humanities (together with research linked to biology, agriculture etc.) will have the possibility of receiving money from regional funds.

National Councils of Ethnic Minorities were created since 2004 and have, among other responsibilities, the duty to conceptualise and develop a cultural policy and strategy specific for each minority.

Last update: September, 2018

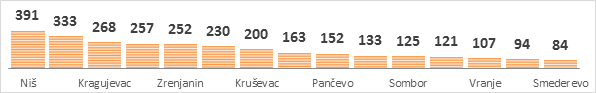

City Councils, created according to the Law of 2007, which gave the status of "city" to municipalities with more than 100 000 inhabitants, representing economic, geographic and cultural centres of the wider region. This status created 24 cities but only 4 have important cultural functions: Belgrade, Niš, Kragujevac, and Novi Sad. Those cities are key partners in developing cultural policy and facilitating participation in cultural life including maintaining a diversified network of cultural institutions such as: theatres, libraries, museums and taking care of free-lance artists. The City Council of Belgrade has founded some of the most important international festivals (e.g. BITEF, FEST, and BEMUS) and cultural institutions which are often of importance for the whole Serbian territory, e.g. the Theatre Museum.

Municipalities (local self-governments) are developing local cultural policies to stimulate participation in cultural life, amateur activities and local cultural institutions and civil initiatives. In Serbia, there are 165 municipalities (out of whom 22 are municipalities under the authority of the cities of Belgrade and Nis), which usually consist of a city with 10 to 15 neighbouring villages (plus, there are several municipalities in Kosovo which rely on funds from Serbia for cultural and other activities, heritage protection, etc. such as Velika Hoča, Gračanica, Kosovska Mitrovica and Leposavić).

Last update: September, 2018

Due to a long term collaboration in the regional independent scene, that started in December 1999 in Sarajevo (continued immediately with project Art generator, an exhibition of contemporary arts in Brussels 2000, curated by Branislava Anđelković, SCCA Belgrade and produced by Violeta Simjanovska, Multimedia Skopje) and developed in the first ten years of the millennium, national organisations of art NGOs had been created in Croatia, Serbia and Macedonia. Later, the regional association Kooperativa was conceived during the conference in Sarajevo (registered in Zagreb in August 2012).

Serbian cultural NGOs created the Association ICSS (Association Independent Cultural Scene of Serbia) in 2011. Amongst the first actions Association issued a declaration inviting the authorities (Ministry of Culture, Belgrade City secretariat for culture, etc.) to dialogue on many issues. The Declaration was signed by 59 Serbian organisations in the field of culture and marked the start of their joint activities to strengthen cooperation and protection of their interests, public interest and promoting cultural life in Serbia.

Ministry of Culture signed the Declaration in 2011, and had more or less regular consultations with Association as a part of their Agreement. However, in 2013, new Minister of Culture abolished the Agreement and seized such practice. Association protested and this act received a very negative public attention. In 2014, cooperation with the Ministry was re-established, only to get worse in 2017 again with the new Minister.

Today, the Association has more than 80 members, involving numerous artists and cultural managers, who produce between 1 200 and 1 500 programmes each year (exhibitions, concerts, performances, theatre productions, panel discussions). The Association organises the festival “On our own engine”, which became an important part of Serbian cultural life. The first edition had 70 programmes on 30 locations all over the city of Belgrade in 2014. It represented an unique insight into the independent culture of the capital. Over the years. the festival made efforts to decentralise its activities. In September 2018, the festival was organised in 11 cities and municipalities across Serbia. Another important action of the Association is the initiation of a magazine for independent culture (MANEK) in 2012, which publishes critical texts, research and reviews of the independent cultural scene in Serbia. So far there have been six issues, the latest was published in summer 2018.

One important member of ICSS is Magacin, a platform/space that regroups several NGOs. It is situated in a former publishing company’s warehouse, which has been adapted into a cultural centre of 1000m2 consisting of several offices, a large gallery/debate room, a dance room for rehearsals and a smaller cinema hall. The space is situated in the Savamala quarter, in the immediate vicinity of Belgrade Waterfront project. It was the first attempt to create a public-civic partnership but Belgrade authorities did not dare to create a new legal model. The solution was that the space would be officially controlled by the House of Youth (a public city institution) while users would be NGOs that will be selected every three years on the base of a public call. The organisations that were selected on the first call (2007) are still there and the House of Youth stopped to perform its monitoring duty (definitely in 2014). Developing a culture of solidarity and mutual support, a few NGOs active in Magacin (Stanica Centre for Contemporary Dance, Karkatag collective, The Walking Theory, and others) offered its space to all those individuals and artists collectives that need public space for performances, gatherings and exhibitions. Thus, “ostavinska galerija” has developed a project called “Openings – your 15 minutes” which gave possibility for many artists to hold a “guerrilla exhibition”. In December 2012, there were thirteen exhibitions and performances and in February 2017 eleven.

Within the event “Space for all” (September 8th 2018), Magacin presented new possibilities and different spaces as well as different art practices that were developed in these spaces. It was not only a presentation of their work, but more an invitation for new collaborations, commons, and co-creation. The team wants to use Magacin as a working space, open to experiment with room for practical and theoretical mistakes, performative actions but also for office work for those in need.

One example of the innovative programmes for whom Magacin is offering space is the Platform for theory and practice of common goods (zajednicko.org), the Studies of commons. Those studies, open to everyone, are conceptualised through lectures and workshops exploring models and concepts of common goods. The aim is to introduce the idea and motivate participants to integrate principles of commons in their different practices, thus contributing to social and cultural change.

Today, the future of Magacin is still uncertain as authorities are ignoring the situation. The model proposed by the Association ICSS to the authorities relies on “established“ practice. This means that Magacin is accessible for all organisations, not just members of the ICSS, which will be realized formally through an open calendar - an online tool in which all interested parties can schedule the use of certain parts of the space. The space would be intended for contemporary artistic creative work (users manage the space on their own). This model does not include an editorial board nor official curators, thus the programme will depend on people and organisations that sign up for its use. It is a centre where people work together sharing their resources, and it offers notable support to small productions that do not have their own space, but need this kind of help in their work. The proposal that Magacin offered the authorities had three solutions: 1) The government should be responsible for implementing it, although this hasn’t been the case in the last 8 years; 2) The establishment of a new institution whose representatives would be both from the authorities and the civic sector, such as Pogon from Zagreb (this was rejected by the City of Zagreb, due to the expenses that would incur); 3) To assign Magacin to the Association ICSS and thereby make the Association responsible for the implementation of the “established practice” model. Till this date (September 2018), the proposal did not receive an official response.

The most important task of ICSS and its members is to advocate for the contemporary arts production and the democratisation of cultural policies. Member Stanica (Station) – Service for contemporary dance – organised numerous actions that are contributing to bottom-up cultural policies. Thanks to them, a value-chain for contemporary dance in the whole region was developed in the form of the Nomad Dance Academy. Another impactful activity was the “deconstruction” of public call results. ICCS analysed these results (Cvetičanin et al. 2018) on numerous occasions and pointed out the misuse of public funds. The research underlined a trend to diminish funds for cultural NGOs and increase funds for NGOs that don’t have culture as their primary focus. In 2016, the Ministry of Culture granted funds to 181 projects from cultural NGOs, while only 107 projects from cultural NGOs received funds in 2017. At the same time, 22 ICCS members received funds in 2016, which decreased to 11 members in 2017. Cultural NGOs received 3 million dinars less in 2017 compared to 2016, while NGOs without cultural focus got 10 million more in 2017. These trends continued in 2018, showing that key criteria in financing cultural projects are not linked to excellence but to the loyalty of the civil society to present governing structures (the authorities). The civil society in culture is usually perceived by the state as a kind of opposition. Due to numerous activities linked to the defence of public space and open criticism of ruling policies in the educational (i.e. against dual education that expelled philosophy teaching from technical schools) and cultural field (advocating for common language; pressures on the use of Cyrillic alphabet; etc.), the cooperation between the state and civil sector is troublesome.

Last update: September, 2018

While the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Serbia is responsible for international issues, the Ministry of Culture is placed in a collaborative position when it comes to artistic and cultural issues in international co-operation and integration initiatives. The National UNESCO Committee is also situated within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and has links with the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Education.

Inter-ministerial co-operation on the level of the Serbian government has not been institutionalised. However, for specific questions and problems or projects, links have been established sporadically. On many occasions, the necessity to create inter-ministerial working groups (even inter-ministerial funds) has been underlined, especially regarding links between culture, education and science. Furthermore, common ties between tourism and culture, also between the cultural industries and the economic sector, have not yet been sufficiently recognised and publicly debated.

However, there is successful inter-ministerial co-operation in the frame of the National Body in charge of the EUSDR – EU Strategy for the Danube Region, which was adopted in June 2011. There are 11 priority areas (PA), involving active representatives of different ministries. The role of PA 3 is "To promote culture and tourism, people to people contacts", involving the cooperation of the Ministry of Culture, Media and Information Society, the Ministry of Economic Development, together with the Tourist Organisation of Serbia and the MFA of the Republic of Serbia.

Another good example of inter-ministerial co-operation is the Joint Commission of the Republic of Serbia and German region Baden-Wuertemberg. The constitutive session was held in Belgrade on 2009, and the second one in October 2011, in Stuttgart, saw the signing of the 2nd Protocol of Cooperation. The members of the Commission are the representatives of all government ministries. The Ministry of Culture, Media and Information Society is represented in the 4th group together with the Ministry of Education, Science and Research. Thus, besides bilateral cultural exchange, the Protocol has also encompassed cooperation in the field of higher education in the field of Arts and Culture.

A similar Joint Commission exists also with the German region of Bavaria and is composed of the representatives of different ministries that are working together on specific issues.

On the other side, an example of the lack of inter-ministerial co-operation is seen when the Serbian Ministry of Science and Technological Development in 2009 drafted a National Strategy for the Development of Science without consulting the Ministry of Culture in relation to Arts and Humanities, etc. The existent inter-ministerial committee is the "Committee for the Support of the Tradition of National Liberating Wars", which actively protects and restores the military graveyards outside of the borders of Serbia. However, three ministers (for culture, science and education) gathered together to sign an agreement regarding the creation of the Centre for Language protection and research in 2009.

There are no inter-ministerial committees or inter-governmental networks responsible for promoting intercultural dialogue. Good practice in this area can be found on the Provincial level. For several years now, Provincial Secretariats for Culture, for Minorities and for Education are running a policy-wide programme to promote Vojvodina multiculturalism through programmes in schools, media and public spaces. However, in 2018 two governmental committees directly under the Prime Minister’s office had been created: the Council for Creative Industries and the Council for Philanthropy, both aiming to support arts and culture.

According to the Prime Minister, creative industries are the fastest growing economy branch and they encompass music, film, photography, radio, television, design, marketing, digitalisation, IT software, gaming, old crafts and architecture, publishing, books, newspapers, magazines, video game publishing, museum and galleries, visual and performing arts. Besides professionals, the Council included leading organisations from the field, such as EXIT Foundation, Nova Iskra, StartIT, Serbian Film Association and Mokrin House (oasis for digital nomads). The task of this Council is to identify key financial and legal obstacles for the development of this sector and the creation of policy recommendations for public policies in this domain.

The Council for Philanthropy has been created on 24th August 2018, led by the Chief of the Cabinet of the Prime Minister and engaging as members eight Ministers (finance, labour, public health, culture, education, state governance and local self-governance, youth, sport, demography and population policy), the Mayor of Belgrade and several representatives of philanthropic organisations (Foundation Ana & Vlade Divac, Hemofarm, Trag, Katalist Foundation, SMART collective, and Forum for Responsible Business). The general aim of this Council is the development of public policies and legal framework for stimulating investments in public (common) good. The idea was based on a research realised in 2016 (Trag and Katalist Foundations) showing that, although tax law suggest the possibility for detaxation if a corporation is investing in public good, there are no more precise legal instruments for the implementation of the paragraph 15 of this law. There are no detaxation possibilities for private persons and donations are submitted to VAT. The framework for volunteering is not favourable and there are no statistics about giving for the common, public good. All of that motivated the Prime Minister to accept the proposal of the Coalition for the development of philanthropy to create such a Council. It is too early to assess the possible contribution of these two Councils, but the fact that eight Ministries are involved is a good sign for the development of intersectoral (inter-ministerial) collaboration.

Last update: September, 2018

In Serbia, following decades of socialist cultural policies, cultural production is still mostly understood as a public good. Hence, for-profit private organisations in culture are very rare (only some fine arts galleries and music and video production houses). Most of culture is produced by civil and public organisations. When it comes to the collaboration between these, it had its ups and downs. Following the period of large tensions between the public and civil art sectors during the 1990s, after 2000, as part of the new hopes for the democratisation of the country, some of the key players of the civil sector moved to the public sector. However, many have left institutions and the tensions between the two subsystems are growing again. In 2011, participants from 59 organisations from the civil sector adopted a Declaration dealing with the development of the independent cultural sector and set up the Association of Independent Cultural Scene (currently 74 members). Soon after, the Ministry of Culture and the independent cultural scene in Serbia signed a Protocol on cooperation in January 2011, on the basis of which the non-institutional actors of cultural policy (initiatives / organisations belonging to the independent cultural scene in Serbia) are to be involved as equal partners in the achievement of general interest in culture and creating cultural policy in the country. The Protocol has been cancelled in 2013, however the cooperation continued (for more see 8.4.2). Judging by the recent planning documents and commentary from the Ministry, most efforts of the Government are going towards the strengthening of the public cultural sector.

When it comes to the public sector, it is very dependent on state funding, which means at the one hand stability and security, but on the other lack of autonomy. As reported by Cvetičanin (2018), national cultural institutions get more than 90% of the funding from the Ministry. Based on the available data[1], examples from Novi Sad and Niš show that local cultural institutions get anywhere from 80% to 95% of the funding needed for their functioning from the city/municipal budget, while they obtain 5% to 20% of their funding from other sources (own income, sponsorships, donations, projects). At the same time, 50% of their expenses cover full-time employees’ salaries, which opens a question of whether they have the capacity to invest in programing and exhibitions.

Table 12 – The budget of national cultural institutions 2015 - 2018

| Total | % | Own income | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | din | 4,196,390.000 | 100% | 347,925,000 | 8.29% |

| 2016 | din | 4,209,121,000 | 100% | 130,800,000 | 3.11% |

| 2017 | din | 4,636,358,000 | 100% | 150,200,000 | 3.24% |

| 2018 | din | 5,188,636,000 | 100% | 150.200.000 | 2.89% |

Number of public cultural institutions in cities (chart 1) and number of employees in public cultural institutions in cities (chart 2)

The city’s cultural infrastructure mostly corresponds to those inherited from socialist system. As there were no possibilities for preservation and reconstruction during the transition period, city authorities today are facing difficulties in restoring and modernising cultural venues. Another problem relates to the restitution laws. In last two years, numerous previously nationalised properties have been returned to their private owners. Many of those buildings hosted cultural institutions (Gallery of Graphic Art, Rex in Belgrade; Cinema Vojvodina and Gallery in Pančevo; Gallery Smederevo; etc.) and now local authorities have to find new premises for these institutions.

The cultural private sector exists in publishing, design, gaming, film production and other related industries which can be connected to the term creative industries. Although they are profit based, some of their activities are not only commercial, and therefore they are also partially subsidised through the public sector and international foundations. More and more private theatres are opened, but mostly in big cities.

[1] The Strategy of Cultural Development of the City Niš 2012 – 2015, Niš, the City of Niš and The Strategy of Cultural Development of the City of Novi Sad 2016-2026 ("Official Gazette of the City of Novi Sad", no. 53/2016).

Last update: September, 2018

Table 13: Cultural institutions financed by public authorities, by domain

| Domain | Cultural institutions (subdomains) | Number (Year) | Trend (++ to --) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage sites (recognised) | 3 093 (2010) | |

| Museums (organisations) | 69 (2017) | ||

| Archives (of public authorities) | 41 (2017) | ||

| Visual arts | public art galleries / exhibition halls | 21 (2017) | |

| Art academies (or universities) | 24 (2010) | ||

| Performing arts | Symphonic orchestras | 4 (2010) | |

| Music schools | 76 (2010) | ||

| Music / theatre academies (or universities) | 6 (2010) | ||

| Dramatic theatre | 43 (2016) | ||

| Music theatres, opera houses | 5 (2010) | ||

| Dance and ballet companies | 5 (2010) | ||

| Books and Libraries | Libraries | 135 (2017) | |

| Audio-visual | Broadcasting organisations | 442 (2010) | |

| Interdisciplinary | Socio-cultural centres / cultural houses | 157 (2017) |

Sources:

Portal of Musical Schools of Serbia http://portalms.galilej.com;

Centre for Study of Cultural Development, Belgrade;

Ministry of Culture, Republic of Serbia; http://www.infostud.com (November 2010).

Last update: September, 2018

There are 513 public cultural institutions in Serbia: 40 are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry, 17 under the provincial Government and 456 under local municipalities. There is some sort of distinction amongst them, as the Law on Culture recognises the National Cultural Institutions of Excellence title. These institutions have access to additional funding and the list grew from 22 to 60 ‘excellent’ institutions in only a few years. Such a great number of institutions with the highest significance is, according to many voices in the field, not balanced with their real capacity and the capacity of Ministry of Culture and Information to support and evaluate their work. The National Museum, National Archive, National Library and Republican Institute for Heritage Protection perform a key role in the overall system of cultural institutions. They also organise professional education and training and they provide monitoring and evaluation services. All these institutions are over-staffed and still lack new professional competences/skills in PR, marketing, fund-raising, human resource management, strategic planning, etc.

Public cultural institutions are facing many problems in their functioning. Their special infrastructure is old and often improperly maintained. Their capacities for contemporary interpretation and presentation are in most cases low. Financially, they are over dependent on public budgetary allocations (in some cases as high as 90%). Another big issue is the ban on employment which prohibits institutions to hire new staff, even when existing positions are lost due to retirement. Such policy – part of the wider austerity measures for the public sector negotiated with IMF – means the discontinuation of some institutions in which the key expert staff is too small for any institutional development.

To engage temporarily additional staff and knowledge, as well as to develop international partnerships, more and more cultural institutions are developing projects for international funders. Recently, an organisation from Serbia became a lead project organisation in the Creative Europe programme for the first time. In 2018, a record number of Serbian organisations received grants from the Creative Europe programme as well. (13 organisations participating in 14 supported projects).

Due to the long but interrupted tradition of corporate sponsorship and the current economic necessity of cultural institutions to fundraise for their projects, partnerships with the private sector could enable a faster development of cultural institutions.

Keeping in mind the current state of the Serbian economy, it is not paradoxical that the majority of sponsorship is currently in the form of sponsorship "in-kind" (in goods and services) which is not expressed in official budgets.

It is also noteworthy to underline that companies used to set up and finance their own art workshops, studios and groups, e.g. Steel Smederevo, Terra Kikinda, Copper mine in Bor, Mine in Majdanpek, etc. Only few of them are still active and receive financial support from the Ministry of Culture for their activities. Some cultural institutions have launched different initiatives to attract money from the private sector. The National Theatre created an "Association of Business Supporters" and the National Philharmonic established a special "V.I.P. Subscription Scheme". The gallery of Matica srpska worked together with private sponsors to refurbish and equip a special room for children workshops. These initiatives represent a new approach to establish links between the arts and business.

Last update: September, 2018

The role of cultural agencies and institutes was extremely important in the first few years of re-opening Serbia to the world, bringing new types of issues within the cultural debate and helping institutional reform. However, only Pro Helvetia, through the Swiss Cultural Programme (SCP) in the West Balkans, was still supporting local and regional cultural activities (the local office in Serbia was closed December 2009), while all the other similar organisations just organise promotional programmes relating to their own culture, or are supporting their own agendas, regardless of real community needs (e.g. the British Council completely closed the library in Belgrade and almost lost its independence in supporting locally relevant projects; the French Cultural Centre severely reduced the budget for Serbia). As a result of the economic crisis, forecasts are even more pessimistic concerning support from the cultural agencies and foreign cultural centres. However, in 2017 the British Council realised a research regarding skills and competencies in the cultural sector as part of their worldwide mapping, aiming to define lacks and needs for the future capacity of building programmes.

The EUNIC Serbia Cluster (established in 2007) started to be active in developing joint collaborative programmes and today has fifteen members and associate members. Most activities relate to the European language day (26th September) and to conferences, workshops and gatherings of different professional cultural associations such as librarians, designers, curators, etc.

It can be said that instruments of international cultural cooperation are not developed and used within certain strategies and programmes. There is no system to enable the long term commitment of public bodies, especially financial (guarantees for the programmes which have to happen in future), which prevents cultural managers from organising big international events or network meetings (although for major sport events, the government is ready to provide such guarantees).

Training is sporadically organised by foreign cultural centres and embassies, in the fields where those embassies decide, or according to NGO or cultural institution initiatives (no Ministry policy involved). This means that the American Embassy organises fundraising training, while Italy is bringing in experts for restoration and conservation, etc. The UNESCO Chair for Cultural Policy and Management at the University of Arts, Belgrade developed a joint Masters programme with two French universities (I.E.P. Grenoble and University Lyon II), and involving other European partners. Another joint Masters programmes has been developed at Serbian universities such as Masters in preventive protection and conservation, contributing to the development of heritage protection professionals.

It is very difficult to make an assessment of general trends in public financial support for international cultural co-operation, as there is no specific budget line or current statistical data, and as projects are supported by different public bodies and through "disciplinary" categories (so, it is not certain if they had an international component and if they got public financing for this component). However, the Ministry conducted research in 2016 about trends in financing of international cooperation for the period 2010-2015 (Dragićević Šešić et al., 2017: 337-399).

To support international cooperation, the Ministry has launched the programme for co-financing (scheme of allocated funds below, that indicates major foreign contributors to Serbian arts and culture scene).

| Competition for co-funding of projects in the fields of culture and art supported through international funds The open calls was first published in 2014. 53 applications were received out of which 28 were supported with the total amount of 14,527,253.15 RSD. Overview of allocated finances by international funds in 2014. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| International Fund | Total allocated in RSD | № of projects | % |

| 1. Council of Europe-Eurimages | 3,106,528.00 | 2 | 21.38 |

| 2. Culture 2007-2013 | 2,630,240.00 | 5 | 18.11 |

| 3. Creative Europe 2014-2020 | 2,013,034.00 | 6 | 13.86 |

| 4. Delegation of the EU (IPA) | 1,785,571.00 | 3 | 12.29 |

| 5. Europe for Citizens | 989,693.00 | 1 | 6.81 |

| 6. The seventh framework programme of the EU (FP 7) | 650,000.00 | 1 | 4.47 |

| 7. European Cultural Foundation | 615,560.00 | 1 | 4.24 |

| 8. Open Society Foundations | 590,000.00 | 1 | 4.06 |

| 9. Balkans Arts and Culture Fund – BAC | 486,745.00 | 2 | 3.35 |

| 10. Erasmus + | 412,363.00 | 1 | 2.84 |

| 11. Société des Auteurs et Compositeurs Dramatiques–SACD | 394,113.00 | 1 | 2.71 |

| 12. Central European Initiative | 351,519.15 | 2 | 2.42 |

| 13. IPA programme of cross-border cooperation Romania-Serbia | 351,887.00 | 1 | 2.42 |

| 14. International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance-IHRA | 150,000.00 | 1 | 1.03 |

| Total allocated funds | 14,527,253.15 RSD | 28 | 100 |

Source: Cultural Diplomacy: Arts, Festivals & Geopolitics

Within the framework of cultural diplomacy, the Ministry of Culture, Media and Information Society organised the promotion of cultural heritage and contemporary art in the multilateral organisations, such as the Council of Europe in Strasbourg (photo exhibition of Serbian landscapes, 2007; concert of Philharmonic Orchestra in Strasbourg, 2007), European Commission (exhibition of Fortresses on the Danube, 2010), UNESCO (exhibition of Fortresses on the Danube, 2011), European Parliament in Brussels (copies of frescoes 2010, paintings of M. P. Barilli, 2011) and, at the end of 2011, in the United Nations in Geneva, there was an exhibition dedicated to the Nobel prize winner, writer I. Andric. Besides traditional and fine art exhibitions, the Ministry of Culture initiates other forms of art promotion of Serbian culture (e.g. photo exhibition "Land of promises, Serbia", or international concerts of eminent young musicians, etc.). Since 2017, the Ministry of Culture is organising a round table: Belgrade’s counterpoint. The aim of this gathering is to offer a debate platform for key world philosophers, artists and writers to discuss major contemporary issues. The topic of the debate in 2017 was “What can literature offer today?” (participants: Peter Handke, Frédéric Beigbeder, Zakhar Prilepin, Yu Hua, and Milovan Danojlić; the discussion was moderated by Vladan Vukosavljević (Minister of Culture and Information) and film director Emir Kusturica,). The topic of the second debate (June 2018) was “What about globalization in culture?” (participants: Zhang Kangkang, Gunnar Kvaran, Vladimir Pištalo, Yury Polyakov, Francisco López Sacha, and David Homel; Vladan Vukosavljević and Emir Kusturica).

The Serbian Cultural Centre in Paris is another platform for presenting Serbian culture abroad. Since 2014, there is an open call for non-institutional actors to apply for the right to present their works and projects in Paris. The Ministry is planning to create a network of Serbian cultural centres in Moscow, Beijing, Berlin, and later in Trieste. The Strategy of cultural development of the Republic of Serbia in the period 2017-2025 (page 111) foresees further widening of the network (including Brussels above all) and emphasises the necessity to plan and reinforce capacities of those centres (starting with the existing one in Paris).

Last update: September, 2018

Within the European framework, after political changes the Serbian Ministry immediately decided to participate actively in all international programmes relevant to the region (MOSAIC, CARDS programme, INTERREG III, Regional Programme for cultural and natural heritage in Southeast Europe, and the pilot project of local development Žagubica and Despotovac linked to the revitalisation of the mining village complex Senjski rudnici).

The working group of the National Convent about the European Union that deals with negotiation chapters Science and Research (25) and Education and Culture (26) was created in 2015. Twenty civil society organisations have participated in its creation. Chapter 26 was opened and temporarily closed on 27th February 2017. The working group prepared a report underlying what was done in this domain that qualifies Serbia for European integrations. The report starts with the fact that Serbia has ratified all the most important UN, UNESCO and Council of Europe’s conventions. Second, that culture is declared to be a common good (area of common interest). Especially important is international and regional cultural collaboration. Within the institutional framework, the report underlines new bodies such as the National Council for Culture and a wide network of public institutions (26). Under recent achievements are quoted: 1) the co-financing of projects that have international and especially EU funding; 2) the programme Cities in focus that endorse decentralisation of cultural life; 3) translation programme stimulating the publishing of Serbian authors in foreign languages; 4) Law on culture; 5) draft of a Strategy for cultural development 2017-2025; and 6) participation in the Creative Europe and Media programmes. Five areas are selected for a further elaboration in the future that are important for European integrations: implementation of the Convention 2005; approval of the Strategy for cultural development; participation in Creative Europe programmes (Culture, Media); support to participation of the City of Novi Sad in European Capitals of Culture programme and, finally, intention to join the European cultural label programme when it will be possible (at this moment, through the open method of coordination, the possibility for non-EU countries to join are debated).

Although chapter 26 deals with both education and culture in 2017 the report of EU commission states only the achievements in the field of education (“Serbia has achieved good level of preparedness in this domain. Certain advancement has been reached in the domain of curricula improvement and by creation of the national agency for Erasmus +. In next year Serbia has to raise participation of children in pre-school education, especially children from vulnerable groups and finalize framework for the national qualification system.”)

There are other chapters that are relevant within the framework of cultural policy, such as the question of Kosovo and Serbian heritage there (chapter 35).

The Ministry of Culture of Serbia prepared a dossier for application for observer status in the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie; its status was accorded at the meeting of OIF in Bucharest held on 29 September 2006. In the meantime, both the University of Belgrade and the University of Arts in Belgrade became members of Agence Universitaires de la Francophonie. The Ministry commissioned a survey regarding the capacity of the cultural sector to be included in francophone programmes and projects. The results showed that only 10% of cultural institutions had language skills, readiness and openness to be involved with such projects.

The Ministry of Culture is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. The first Quadrennial Periodic Report has been submitted in 2014 and the new one is currently under preparation. In the new report, contribution of civil society has been taken in account although the Association of the independent cultural scene in Serbia has complained that their achievements are presented as collaborative achievements although the public support for NGOs that are active in the contemporary arts production is lacking.

Within the cooperation agreement with the Council of Europe, three conventions have been signed in September 2007: European Landscape Convention, Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro convention) and the European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage during the Central Celebration of the European Heritage Days in Belgrade. One of the most significant events was the ratification of the UNESCO Convention for the promotion and protection of cultural diversity on29 May 2009.

Last update: September, 2018

All major national institutions in Serbia have many cooperation protocols and agreements signed.

The policy focus, since 2001, was on joining the European and regional professional / sectorial networks and associations, to develop international cooperation and exchange, while, at the same time, singular links are established among relevant institutions.

The Ministry of Culture participates actively in the organisation and coordination of European Heritage Days. Every year, it is directly involved in the organisation of the central celebration on the national level and Belgrade and Serbia were the hosts of the 2007 Launching Ceremony of the European Heritage Days. This event is used in the context of decentralisation, as one of the priorities of the Ministry (in 2009. the focus was on the multicultural city of Prijepolje).

The National Museum in Belgrade has more than ten cooperation protocols with major European museums regarding the exchange of exhibitions and the exchange of curators. Within this scope of cooperation, several major projects have been realised, such as In touch with antics - with the Louvre (2006) or the exhibition of the European art collection of Belgrade National Museum in The Hague (2005). Also, the National Museum is active within ICOM and ICCROM, having signed a cooperation agreement with the latter. Because the doors of the museum have been closed to audiences since reconstruction started in 2001, most of the productive activity of the museum is international cooperation - exhibitions abroad and exchanges of art works.

The Museum of Contemporary Arts, as one of the oldest museums of its kind in Europe, cooperates widely and extensively with similar key institutions abroad, resulting in many important exhibitions like Museum Stedelijk Amsterdam at Usce (curated by Serbian curator B. Dimitrijević, which represents a precedent in the museum's policy). Along this line, the Museum also organised an exhibition of British Contemporary Arts, curated by three Serbian curators. Important links exist with MACRO, Roma, etc. Major regional and international exhibitions had been organised since 2001, such as the cross-referencing project Conversations in 2001 (when curators and artists from different countries of the region created projects in dialogue with each other), or the Last East-European exhibition in 2004 linking curators and artists from the region.

In the field of theatre, Yugoslav Drama theatre has the most extensive international cooperation. It was member of the Convention Theatrale Europeene, and now is a member of Theatres de l'Union de l'Europe, and recently, NETA (New European Theatre Action), launched by 11 theatres in Balkan countries.

The National Theatre of Serbia has participated in the first project connecting Teatre Lliure in Barcelona, Spain; Akademie für Darstellende Kunst in Ludwigsburg, Germany; Dramaten – Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern in Stockholm, Sweden; and The Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark. The title of the performance was “Topographies of Paradise” and Madame Nielsen’s major project on European national(istic) visions was presented for the first time on August 25th, 2018 at The Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern during the Bergman Festival in Stockholm. The performance will go on a small European tour to Belgrade, Copenhagen and Barcelona.

BITEF Theatre is part of ENPARTS (European Network of Performing Arts), working together with La Biennale di Venezia, Dance Umbrella, Berliner Festspiele and other partners in creating experimental co-production theatre, dance and music projects, supported by the European Commission.

The Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad (a central theatre institution of the autonomous province of Vojvodina) has signed agreements on cooperation with theatres and theatre institutions in Macedonia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Slovakia, Romania and Switzerland. This kind of co-operation includes: co-productions, exchanges of artistic experience, know-how transfers, exchange of performances etc.

The Belgrade Music Festival BEMUS has been accepted into the European Festivals Association, among 100 of the most prestigious music and theatre festivals in Europe. The Belgrade Youth Centre is active within IETM, as well as several other NGO theatres. Serbian NGOs are connected and active in the European and world networks, such as Dah Theatre, which is a member of the Magdalena network, or Remont, which has actively participated in the creation of several Balkan networks (BAN, SEECAN, etc.).

In the field of librarianship, professional cooperation has been established within IFLA and Eblida, and more than 50 bilateral agreements of cooperation have been signed between the National Library of Serbia and the most relevant European and world national libraries. The National Library is a co-founder of the TEL project (The European Library) – a Catalogue of European National Libraries and Digital Collection of European Literary Heritage (since 2005). The National Library joined The World Digital Library in April 2008. The National Library collaborates also within the Europeana (the European Commission's digital platform for cultural heritage).

Continuous professional development is organised through study visits and peer exchange within CALIMERA – Cultural applications: Local Institutions Mediating Electronic Resources project for a network of city libraries of Belgrade (knowledge transfer and exchange of experiences). The Calimera project is part of the IST programme of the EU Commission, including all the countries of the Western Balkans, led by Slovenia as the coordinator. One example of a project carried out within Calimera is the Serbian Children's Digital Library, with 120 books, contributing towards the overall aim to have 10 000 books in 100 languages within a world network.

Cinematography, since 2000, has been developed relying a lot on co-productions – so that nearly half of the production has international, mostly regional co-producers. At the same time, the Film Centre of Serbia had granted subsidies for 4 co-production projects from Southeast European countries. A few film projects succeeded in obtaining EURIMAGES grants, and a few obtained funding for scenario development (from the Paul Nipkow Fund Berlin, Southeast European Fund, etc.). In the period 2010-2015, more than half (53.75%) of the projects supported by the competition for cinematography and a total of 68% of the total budget for this period was allocated to co-productions. The number of supported projects is constantly increasing, as well as the competition’s budget (with the exception of 2013). This increase in budget, but also the increase in the percentage of allocation for international projects, was noticeable in 2014 and 2015.