1. Cultural policy system

Slovenia

Last update: December, 2014

The historical development of cultural policy in Slovenia has gone through extreme change. Four distinct periods of transition and development of cultural policy following World War II can be identified, which also reflect the major ideological transformations of recent decades. The first three periods take place during the period when Slovenia was one of the six republics of the ex-Yugoslavia, while the last is connected with Slovenia as an independent democratic state:

Up to 1953: party-run cultural policy when culture was openly used as a propaganda tool of the Communist machinery;

Up to 1953: party-run cultural policy when culture was openly used as a propaganda tool of the Communist machinery;- 1953-1974: state-run cultural policy characterised by extreme territorial decentralisation with communities that were not independent self-government entities but primary political units that executed governmental tasks;

- 1974-1990: self-management system of devolution when cultural programming was delegated to the self-managing cultural communities and the provision of cultural services to cultural producers that were not part of the administration but separate legal entities; and

- 1990-present: parliamentary democracy, with a return of cultural policy in the hands of public authorities and their state apparatus.

As is true of most small countries, it was through culture that Slovenes constituted themselves not only as a nation but also as a state. It is from this special emphasis on culture that the so-called "Slovenian cultural syndrome" was derived. Thus, it is not surprising that the starting point of the disintegration of Yugoslavia, in the 1980’s, was the Slovenian fear of jeopardising its culture, language and national identity, which was provoked by an attempt by the central government in Belgrade to unify national interests and subordinate them to the Serbian majority, through the mandatory core Yugoslav curriculum of literature and language ("Yugoslav cultural canon"). This fear united professionals, intellectuals and politicians, regardless of their ideological or political orientation. Driven by "centrifugal forces of ethno-politics and ethno-economics" Slovenia became a nation state for the first time in June 1991, when the Eastern Bloc of Cold War started to collapse, which removed the most compelling Western reason for working to keep the Yugoslav state together.

The central role that culture played throughout Slovenia's history created an atmosphere whereby artists had more "space" to develop their own projects and to organise themselves in independent associationseven during the socialist regime. Although in the years following the Second World War, certain writers and a list of books were removed from public libraries, the state systematically established new cultural institutions, enabled operation of central professional associations and supported the works of artists, recognising the power of culture in creating the new order and showing how flourishing, inspiring and successful it was. With an effective system of administrative measures, the state also "intervened" in their work through administrative measures to suppress problematic journals (for example Beseda (1956), Revija 57 (1958), Perspektive (1964)), or ban suspicious artistic texts (for example Muževna steblika (1967)) or performances (for example Topla greda (1974)) and even to close avant-garde theatres (for example Oder 57). On the other hand, they allowed the establishment and funding of new ones all over again. Since a well-thought and effective system of preliminary censorship was set in place, plays, films, books, and performances were often banned before the opening, or in the middle of rehearsals (an intervention always executed silently and invisibly to the public) and almost no documents or traces survive of these cases. The result was a very small number of Slovenian political decedents and an overwhelming public apparatus that absorbed the majority of the most important intellectuals and artists. The relationship between the political authority and civil society could be therefore defined as a repressive tolerance. There were also some taboos, such as the publications of political immigrants who left the country at the end of the World War II to escape Communist persecution and kept a very intensive cultural life in diaspora.

But there is also a strong social-democratic element to be found emerging with great vigour after 1945, when the masses were to be given access to the arts which had been previously only been accessible to the rich and the disgraced aristocracy. Collectivisation of arts went along with another expression of de-elitisation of art going through the cultural policy, favouring amateur culture, which therefore permitted the setting up of cultural associations. Therefore, three parallel cultural scenes evolved at the end of the 1970s / beginning of the 1980s; often in opposition to each other: established institutional culture supported by the authorities, amateur culture assisted by quasi-governmental umbrella organisations and independent alternative culture tolerated at the margins. Due to the preferential treatment of "progressive", "socialist" currents, the first two components enjoyed structural funding while the third one got some project funding occasionally.

When most of Europe was creating centralised models for cultural policies during the 1950s and 1960s, Slovenia, like other Yugoslav republics went through a process of decentralisation. Contrary to the "positive image" decentralisation has today, the lack of local money almost destroyed the institutional cultural network in Slovenia and the process was viewed by prominent artists as a facade and a manipulation in order to break cultural nationalism in all six republics of ex-Yugoslavia into harmless units and to enable, via the local level, easier control over "fragmented" culture. Another important feature in the general political scene of the late 1960s was some attempts at liberalism in the economy but the process was associated with the national egoism of the most developed republics; the liberals were slipping from power and became a target of conservative ire.

Although the cultural policy was affected, in the first part of the1970s, by a clash with the liberalism of the late 1960s, the development of cultural policy took a sharp turn when Slovenia was granted more autonomy from the Yugoslav Federation in the area of culture. This era was otherwise known as the period of "self-management" when responsibility for cultural programming was delegated to the cultural communities, where it was debated and created by both producers and consumers of culture. Thus, in the field of cultural policy, political units (the republic and the local communities) were replaced by interest units (cultural communities). Local cultural communities (approximately 60) had a great deal of power in decision-making and resource allocation on the local level. According to the concept of polycentric development, the larger municipalities became cultural centres (ca. 25) and decentralisation remained a key political orientation. Later, national culture finally obtained its place within the Cultural Community of Slovenia and, in the 1980s a national cultural policy platform was created. Considered to be one of the most important periods in Slovene cultural policy history, the Cultural Community of Slovenia and 60 local cultural communities formed a strong administrative apparatus, which raised the level of cultural policy-making, empowered its place in society and created favourable conditions for cultural development. From a functional aspect, the self-management model proved to be ineffective as it was over regulated, centralised and exclusive. The author of the system was himself aware of the increasing conviction of his contemporaries that self- management is at best a formality and at worst a fraud. According to the well known sociologist Josip Županov, the system was considered utopian, with little connection to reality, It experienced economic failure even before political difficulties occurred. The self-management system came to an end in 1989, but the utopian nature of the self-management model was evident already in the middle 1980s, when an economic recession forced the state to take over the local funds for cultural institutions in order to preserve them.

Separate laws for each cultural activity were created as each was "of special social concern". The main difference between the Western European system of public service and the Socialist regulation in Slovenia is the following:

- the public service system is only an organisational forum for public authorities to organise cultural provision without any ambition to drive out private cultural providers; and

- the socialist model highly regulated cultural activities and entrusted them to the institutional monopoly and the professional initiatives of private organisations, i.e. alternative culture was forced to withdraw into the sphere of amateur culture.

Only in the 1980s did the state allow the possibility for private activities in the sphere of culture and the status of a freelance artist and special register were introduced. Before the introduction of this status, there were only state artists to whom the state provided social security contributions, while tolerating that some technical film workers and translators settled their pension assurance directly with the agency. Similarly, the central artistic associations, which functioned as para-governmental organisations, were also budget-financed. The state in this manner controlled all the organisational forms. Nevertheless, the Association of Slovenian Writers evolved into a driving force for democratic change and independence.

After the death of the charismatic socialist leader Josip Broz Tito, the communist party started to lose its undisputed position. The authorities became insecure and at the same time apprehensive about democratic and social processes striving to achieve independence. They became aware of the actors fuelling these processes originating mainly from the cultural field. Culture was certainly a cradle nurturing these processes. The 1980s were, therefore, the golden years for the Slovenian cultural infrastructure and its artists: from the point of view of artistic freedom and societal financial support.

In spite of the adoption of a new legal framework in 1996 (Exercising of the Public Interest in the Field of Culture Act (now translated as the Act Regulating the Realisation of the Public Interest in the Field of Culture)to replace the self-management cultural model with a democratic paradigm, the cultural system has not yet experienced significant structural changes in terms of shifting from paternalistic to neoliberal discourse. In fact the image of the democratic transition in the arts context was far from the cultural policy trends going on in the 1990s in Western Europe; trends which have been marked by a pervasive managerialist and market reasoning in the public sector that undermined the autonomy of art. On the contrary, the sector's strong belief in artistic autonomy anticipated the cultural policy inspired by legacies of romanticism and idealism based on certain norms such as "subsidy for arts' sake" and "funding without strings". Therefore the democratic transition has never meant any sacrifice of artistic goals to the whims of the democratic majority or neoliberal tendencies. A weak cultural market with underdeveloped support schemes and tax incentives could not present a reliable alternative to the traditional model. Without any additional budgetary injections to place culture in the centre of social development and mobilise its economic potential, the only natural response was a defensive attitude towards changes that resulted in the perpetuation of traditional meanings and functions of culture.

The democratisation of culture in Slovenia had already started with the self-management system. Therefore, the Slovenian cultural policy developed at an incremental pace during the process of transition in the 1990s. In the new situation, when culture lost its ideological and national-legitimisation potential, the transition was therefore reduced to accommodating democratic procedures. The former socialist concept of culture as the area of special social meaning was translated into the democratic concept of public interest for culture, where the responsibility for cultural policy was, after the abolishment of the self-management system in 1990, returned to public authorities. The socio-political governance structure executed through cultural communities was transformed into a representative democracy, where decisions were taken by elected politicians on the national and local levels. The system of juries of peers nominated by a minister to decide on the quality of the artistic propositions was established but with an advisory role, as the final decision rests with the minister. However, the ministers as a rule follow the proposals of the juries. In the situation of the ever smaller project funds this system could also serve as an alibi for the absence of political engagement. The public authorities now equipped with the democrat mandate left the field of culture to become an internal affair of the cultural circles as it lost its previous central role in nation-building. The positive notion of the arm`s length principle has blurred the problem of such political marginalisation of the cultural sector, which consequently became more insular and inward looking. In this situation, the explosive growth of the cultural industries, the digital revolution and the liberal trade pressure found cultural policy and the cultural sector unprepared. After the abolition of the self-management system, there was no explicit cultural policy in Slovenia until the adoption of a new National Programme for Culture 2004-2007. But even afterwards no structural changes have happened.

Therefore all essential systemic transitional changes were brought by the general reforms such as privatisation, local community reform, the public finance system, the tax system and the civil service system. The latest system that was based on the traditional bureaucratic model of all employees as public servants was accepted by both the cultural policy and cultural sector without any hesitation.

The changes can be summarised as follows:

- the privatisation of publishing houses, cinemas and the media;

- the de-nationalisation of some venues previously used for cultural purposes including some cultural monuments that were given back to their former owners (in both cases mainly the Roman Catholic Church);

- new higher taxes on cultural goods and services;

- the reform of local government and the introduction of integral local government budgeting, where the local governments self-define their own priorities;

- attempts to set objectives for programme budgeting and related financing;

- the enforcement of a unified salary system for all civil and public servants, rigid hiring-firing and administratively regulated promotions; and

- overall explosion of auditing activity with constant checking and verification.

Although international foundations such as the Open Society Institute invested some resources in the modernisation of the cultural sector, it was limited to independent cultural projects, organisations and art initiatives. This support has not succeeded in creating the critical mass of organisations and individuals that would have the capacity to initiate new production and dissemination forms and models. When this assistance ended, the Slovenian independent cultural scene found itself in financial insecurity, which remains a parallel structure without serious chance of becoming part of the mainstream. Meanwhile, the mainstream cultural infrastructure, composed of public institutions, preserves the characteristics of state bureaucracy with the system of public servants at the top.

Slovenia began accession negotiations with the European Union in 1996 and became a member state in 2004. The harmonisation of legislation, and its implementation in the field of culture, began mainly in two areas: the harmonisation of media legislation with the European Television Without Frontiers Directive and the introduction of VAT (in accordance with the 6th Directive of the EU) on books and audio-visual material. The latter has had a negative impact on Slovenia's culture industries. The question regarding the implementation of the Council Directive on Rental and Lending Rights and on Certain Rights Related to Copyright remains open. Slovenia's position is to maintain library compensation measures in all public libraries and not on authors' copyright. It was also necessary to amend legislation considered discriminatory for the citizens of EU Member states, i.e. in the field of employment, the establishment of business etc.

The moment of joining the EU could be considered as the end of the transitional period, at least concerning all those areas that fell under acquis communitaire. Although culture represents an area of shared responsibility between member states and the EU, the principle of subsidiarity preserves national sovereignty over non-commercial cultural activities. In spite of the fundamental changes in the political and economic spheres, significant structural transition in the public cultural sector has not occurred yet. Thus, the huge infrastructure of public cultural organisations has remained unexamined, unchanged and unchallenged and doubt regarding its functional and rational operation is further eroding its credibility.

Main features of the current cultural policy model

According to the Act Regulating the Realisation of the Public Interest in the Field of Culture (2002), the main elements of the current cultural policy model are:

- The central role of public authorities in the area of culture: the Constitution of the Republic of Slovenia defines itself as a social state. The further development of cultural goods as public goods and related presumption of public interest for culture are also part of this paradigm;

- Intensive regulation but weak monitoring: there areno regular activities to monitor the implementation of regulation. Existing administrative inspectorial supervision of the performance of statutory and regulative provisions in the area of culture and media by the Inspectorate of the Republic of Slovenia for Culture and Media, a body incorporated within the Ministry, cannot replace regulatory impact assessment as a regular governmental activity;

- Complicated procedures but weak ex-post evaluation: the process and procedures to distribute public funds aimed at increasing transparency and competitiveness are in fact difficult and frustrating for both the cultural administration and for the receivers of public funds. Once the funds are distributed through the public tenders there is no evaluation of whether their objectives were achieved;

- Expert advice on financial decisions: several expert committees for individual disciplines (17) composed of artists and other concerned professionals prepare the proposals for financing,

- Heavy institutionalisation of Slovenian culture: public cultural institutions emerged out of the civic initiatives which began in the 19th century. They were nationalised as a consequence of regular financing received during the first decades of the last century. After the Second World War the communist ideology created a monopoly over professional cultural activities. Due to the neoliberal pressure, and in the sunset of welfare policy, de-etatisation has lost its appeal and institutional status remains the most appreciated format for cultural operation.

- Public cultural institutions are not part of state or local administration: as a legacy of the previous ex Yugoslavian self-management system,all institutions are separate legal entities under public law with full legal and business capacity and their own management structure. Nevertheless, a central system of public servants and budgetary funding procedures define strict frameworks for their operation;

- Multiannual programme financing: in 2004, besides annual project funding, three-year structural financing for NGOs was introduced. Due to the limited financing at both national and local levels the independent cultural sector still lacks recognition and support for its new models of production, innovative work practises and collaboration;

- Decentralised cultural infrastructure: The main concept for cultural development applied after the Second World War was polycentric, and based on approximately 25 traditional cultural centres in Slovenia. Municipalities are in charge of museums, library activities, amateur cultural and art activities and other cultural programmes of local importance. In areas where national minorities live, the municipalities are also obliged to support their cultural activities. There is no intermediate level of government between the state and local authorities yet;

- Policy of extensions: no new construction or any developments in the national cultural infrastructure (even the new National Library project remains unfulfilled for more than a decade); there is only renovation of historical buildings (e.g. Slovenian Philharmonia, Opera House, Modern Gallery, Metelkova premises, Slovenian Kinoteka).

However, there is an explicit political announcement (in the last three national programmes for culture- 2004-2007, 2008-2011 and 2014-2017) regarding the modernisation of the public cultural sector or even the introduction of the new cultural model, but without any concrete results, as every substantial proposal was faced with strong resistance from the field.

The main elements of the allocation of state funds are:

- State funding model: Due to the small cultural market, traditionally paternalistic relations between public authorities and the cultural sector and weak tax incentives for cultural activities highly depend on public funding;

- High fixed part of the annual state budget for culture: Since the majority of state public funds goes to public institutions (ca 70%), new modes of production are financially marginalised (ca 6%);

- Centralised funding of larger municipal institutions: The establishment of local governments, which would independently take decisions on their own priorities, presented a threat to the decentralised concept. Therefore, since the middle of the 1980s, all larger municipal cultural institutions (ca 40 - 12 theatres, the rest are museums) have been state financed. However, local governments independently manage these institutions and appoint directors to their respective councils.

Cultural policy objectives

The general objectives of Slovene cultural policy are determined by the Act Regulating the Realisation of the Public Interest in the Field of Culture (2002). They are: supporting cultural creativity, access to culture, active participation in cultural life, cultural diversity, cultural heritage conservation and development of Slovene cultural identity together with the development of so the called Common Slovenian Cultural Space, which includes Slovenian minorities living in neighbouring countries: Italy, Austria, Hungary and Croatia. According to this Law, further policy elaboration is left to the National Programme for Culture, defined as a strategic document for the permanent and integral development of Slovenian culture.

The first one was adopted for the period 2004-2007 followed by the second one for the period 2008-2011. The main characteristic of both documents are the abundance of objectives (more than 40) and a lack of priorities and feasible indicators to measure their realisation. More radical changes were promoted in the introductory notes of the National Programme for Culture 2008–2011, which it was hoped would bring about reform of cultural policy and provide more opportunities for creativity in the four year period.

The unstable political situation from 2010 on and related frequent changes of the minister of culture made it impossible to adopt the national programme for culture on time by 2011. One illustrative comment was that in spite of this political handicap the cultural sector did not stop functioning normally. Finally, the Minister of Culture (March 2013 to August 2014) succeeded in finishing the legislative procedure and a new National programme for culture for the period 2014-2017 was adopted in 2013. The programme had the following objectives;

to preserve and develop the Slovenian language; to promote cultural diversity; to ensure access to cultural goods and services; to support artistic creativity and artists; to encourage and promote cultural education in schools; to educate young people for cultural professions; to encourage the culture industries and major investments from business to culture; to encourage the process of digitalisation; to modernise the public cultural sector in terms of better efficiency, openness and autonomy; and to improve the situation of NGOs.

The programme underlines three leading principles, namely excellence, diversity and accessibility, yet all three are of course very loose names for the general cultural policy principles and cannot serve as direction-serving concepts. The main novelties are therefore the introduction of the cultural and creative industries and cultural market discourses and the explicit mention of the labour market in the cultural sector (as a crossover topic covering the public sector, the NGO sector, those self-employed and private companies in culture). It defines the objectives of an increase in employment in NGOs, the private sector and self-employment.

In promoting the new programme, the Minister said it would provide "a compass and a new model for Slovenian culture". Other main differences between the old and new programmes are the lack of a preamble (the programme for 2014-2017 is based purely on concrete sectorial, intersectorial and crossover measures while the programme of 2008-2011 starts with a longer preamble explaining the main conceptual issues in cultural policy); the lack of a financial plan (the programme for 2014-2017 features only calculations for individual measures and lacks a complete picture); a special final chapter in the programme for 2014-2017 is dedicated to the EU Structural Funds a with short description of the sectors where the funds should be used; and a change in buzzwords, characterising the programmes – while the programme for 2008-2011 was based on syntaxes, such as "intercultural dialogue" and "public-private partnerships", the programme for 2014-2017 is based on different, "catchy" buzzwords, such as "markets in culture" and "cultural and creative industries". While it is still too early to judge the success of the 2014-2017 programme, one can easily observe that almost nothing has changed in the field of public-private partnerships in culture (the only really publicly acclaimed project, the renovation of Ljubljana's old Rog Factory, didn't manage to get any private partner at all, to be finally supported purely by public resources). Another interesting thing is that the accepted programme for 2014-2017 doesn't mention the consequences of the financial crisis which echoes the (non-)response to the crisis of past governments.

The envisaged support for the new topics in the programme for 2014-2017 will depend on European cohesion policy funds. The data for 2013 shows that the national funding of the public institutions was, in the time of crisis, on the increase, while the ‘third’ sector remained level. This indicates that it has not been possible to accomplish the Minister’s mandate to fulfil the promise of a "new compass" or new model. The next Minister took office in September 2014 after a premature election.

Last update: December, 2014

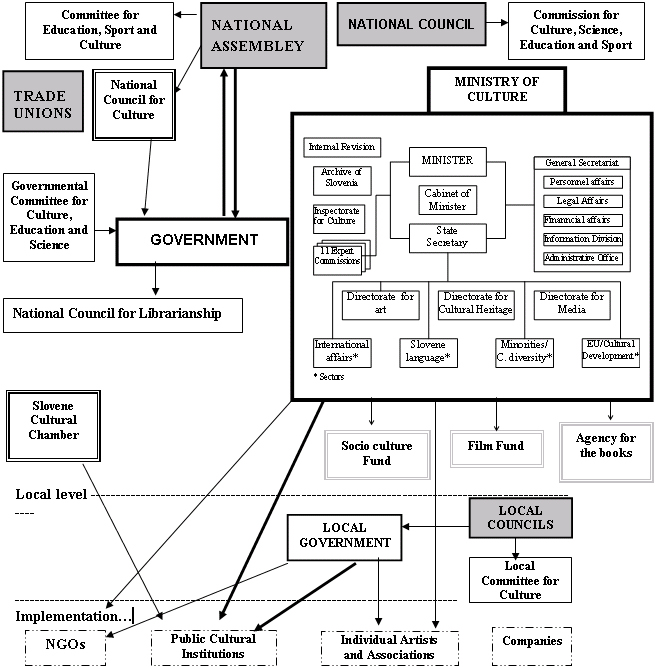

National Level Decision-making bodies

Last update: December, 2014

Slovenia is a social and democratic republic with differentiated legislative, executive, and judicial powers. Its cultural system is a complete set of institutions (political and cultural), interest groups (such as political parties- currently seven of them are represented in parliament, trade unions, lobby groups- associations of artists of individual discipline), the relationships between those institutions and the political norms and rules that govern their functions (constitution, election law, general and cultural legislation). The Parliament is composed of the National Assembly that has legislative power and the National Council that represents interest groups of employers, employees, farmers, crafts and trades, artists and other independent professions, non-commercial fields and local interests. Since the final legislative power rests with the National Assembly, one of the more important roles is the creation of links with civil society, mostly professionals.

The National Assembly deals with culture in general through bills, national four year programmes for culture and annual state budgets. On a more concrete level, cultural matters are addressed through Parliamentary questions and motions forwarded by individual deputies and their groups to regulate individual issues or to adopt certain measures within the scope of the work of the government, a minister, or a government office.

Civil society and experts can participate in the formulation of cultural policies in four ways:

- through membership of the minister's advisory bodies for different cultural fields;

- through the National Council for Culture;

- through the Cultural Chamber of Slovenia; and

- through participation in the governance structures of public institutions.

The National Council for Culture and the Slovene Cultural Chamber were established to include the voice of the public (mostly artists) in the new policy process. However, the Slovene Cultural Chamber exists more or less on paper, only without any distinguished role so far while the National Council for Culture (NCC), an independent body appointed by the National Assembly for a five year mandate, is supposed to demonstrate the right of the cultural sector to hold a dialogue with the public authorities on the highest level. The National Council for Culture:

- monitors and assesses the impact of cultural policy on cultural development;

- gives opinions on the national programme for culture and annual reports on the implementation thereof;

- discusses proposals of laws and other regulations in the field of culture and those that are related to it; and

- gives suggestions and proposals to public authorities while having a right to obtain a response within 60 days.

The administrative and technical support for the Council and funds for its operation are provided by the ministry.

The current Council was appointed in July 2014 with a five year mandate, just a few months before the new coalition came to power in September 2014. In the previous five year mandate, the Council held 31 meetings. In 2013 it had 6 regular meetings, one extraordinary and nine correspondence sessions, two meetings of the working group and two panel discussions in different cultural institutions. Its annual budget for 2013 was around 13 000 EUR but it only spent 7 500 EUR, mostly on operational costs and some minor commissions. No funds were spent in commissioning analysis or research. At its final session in the old composition, its president stated that after 15 years of his activities in the advisory bodies of the ministry and 9 different ministers, his conclusion is that policy decision-makers do not follow the initiatives and proposals of the bodies they create. However, the end of the mandate has not been accompanied by any analytical material.

There is also the National Council for Library Services envisaged in the Librarianship Act (2001), but at the level of government. The Council is a professional and consultation body that decides on professional matters in the field of library services as well as handles and gives opinions on all technical issues from the field of operation and development of libraries. Members of the Council are recognised experts for all types of libraries who are nominated by the Government of the Republic of Slovenia on proposals of different stakeholders (ministries, professional associations and the academic sphere).

The National Council for Library Services conducts the following tasks:

- adopts technical recommendations in this field;

- gives preliminary opinions on all regulations related to the library services;

- discusses technical baselines of the library services;

- discusses technical baselines for the operation of the National Mutual Bibliographic System, monitors the operation thereof and coordinates its development;

- gives opinions on development plans, annual work programmes and financial plans of the national library and library information service;

- discusses annual reports on the operation of the national library and library information service and reports to the relevant government ministries; and

- proposes initiatives and proposals from its field of work.

The Slovenian cultural policy model is regulated by the Act Regulating the Realisation of Public Interest in the Field of Culture (originally adopted in 1996 and revised in 2002 with the additional amendments over the years, the last in 2013). The title itself indicates that the model is based on the presumption of public interest for culture, the substance of which is defined in depth by sector specific legislation (see chapter 4.2) and national and local programmes for culture, while the Act itself defines the structures, mechanisms, procedures and rules for the articulation and implementation of this interest. The responsibility for public provision of cultural goods and services lies in the hands of state and local communities.

Harmonious cultural development across the whole country, known as polycentric cultural development, is a basic cultural policy orientation that has been in place for decades. All municipalities (210) are responsible for local cultural life but larger ones (25) have an additional obligation, as traditional cultural centres, to ensure the operation of those cultural institutions of broader importance. Until now, the state helped them by funding these institutions (40 - mainly theatres and museums) from the state budget, even though they are part of the municipal cultural infrastructure. In order to ensure common standards in the field of librarianship, museums, monument protection[1] and archives, these fields are regulated as uniform public services. Thus municipalities (210) have legal responsibilities for local museums and all public libraries as public services, while monument protection and archives are primarily the responsibility of the state.

Local communities are independent self-government bodies. Therefore they can adopt their own rules and procedures to execute their responsibilities for culture. If they don't use this discretion they have to follow mutatis mutandis, the provisions for state authorities. Until now this responsibility has been carried out in a reluctant manner out of the fear that without adequate local budgets and other prerogatives, local authorities cannot be trusted to take proper care of cultural institutions.

The formulation and implementation of cultural policies is an outcome of different procedures and interactions between the cultural administration, government, parliament, the arm's length bodies, local governments (municipalities), cultural institutions, NGOs, individual artists and their associations.

The ministry formulates proposals for the government, which then submits draft laws to the parliamentary procedures. The main role is reserved for Parliamentary Committees comprised of deputies from all political parties of the Parliament. The field of culture used to be included in Parliamentary Committees for Education, Culture and Sport. These changes in legislative procedure substantially reduced the role of the Ministry of Culture in this process.

The Ministry fulfils its responsibility for cultural policy formulation and implementation through:

- preparation of proposals on sector specific laws and their implementation (including monitoring);

- co-operation with other ministries in the formulation of general legislation and sectoral policy strategies that have an impact on culture;

- coordination of drafting and implementing of the National Programme for Culture, the main strategic document;

- preparation of the annual report on implementation of the National Programme to the Parliament with an evaluation of results and proposals for necessary modifications;

- the provision of cultural services via national cultural institutions founded by the state;

- establishment of procedures and criteria for budget allocations to NGOs and individual cultural projects; and

- interventions to finance larger cultural institutions founded by the municipalities.

The Ministry executes all of the above tasks in the fields of the arts, heritage, the national library and public libraries, the culture of minorities in Slovenia and international cultural co-operation. It is also responsible for the media (audio-visual sector) and the press.

The Minister has expert commissions as his advisory bodies for individual fields or aspects of culture to assist in examining the most important issues related to the regulatory measures, organisation of the public service, distribution of public funds and awarding of various social rights

There are also two public agencies and one public

fund, which all function as arm's length bodies distributing public

funds: the Slovenian Film Centre – public agency, Public Fund of the

Republic of Slovenia for Cultural Activities (dealing with amateur

culture) and the Slovenian Book Agency.

[1] To give an example here are the jurisdictions of local communities in the field of cultural heritage:

- To declare the monuments of local importance by legal decrees

- To decide on ways of protecting heritage by processes of spatial planning

- To prepare plans of protection and salvaging (including heritage)

-

To allocate financial support for direct renovation measures to

monuments and heritage (forming special endowments out of their budget)

- To manage cultural heritage in municipality ownership

Please find the available information on this subject in 1.2.2.

Please find the available information on this subject in 1.2.2.

Last update: December, 2014

The NGO and advocacy sector has been going through significant changes in the past years. Several new organisations being primarily representative and advocacy oriented have been formed: Asociacija and Open Chamber for Contemporary Art being the best known of those. Asociacija was formed in 1992 and was a non-professional advocacy organisation serving mostly the so-called "independent producers of art" until 2009. Starting in 2009 it was given a European Cohesion Fund grant which stirred its professionalisation and large increase in its membership and activities. In communication with previous minister Majda Širca and her state secretary Stojan Pelko, a working group for dialogue with the NGO sector in culture was formed consisting of seven representatives from the NGO sector and a number of participating ministry employees. Soon a similar group for those self-employed in culture was also formed. The groups served to provide a platform for dialogue with the NGO sector and those self-employed in culture. Asociacija was also very active in advocacy on the local level, organising a group to communicate with the NGO sector in the City Municipality of Ljubljana.

In the dialogue groups, a number of legislative improvements for the NGO sector and those self-employed in culture have been discussed, mostly addressing the changes of the Act Regulating the Realisation of the Public Interest in the Field of Culture, particularly the stronger inclusion of the NGO sector in this legal act (which serves as an umbrella law in the field of art). Also, changes in financing, social security measures for those self-employed in culture, public tendering procedures and representation of the NGO sector have been discussed, although to date not leading to any significant and expected changes.

The dialogue groups have been formed again under the new minister Žiga Turk in 2012. Several accusations from Asociacija (which again served as instigator of the groups) have been addressed to the Ministry for not following the proper procedures of appointment and work in groups as well as non-participation of key persons of the Ministry in groups. Many issues have been raised again under Minister Uroš Grilc in 2013 and the dialogue groups have been formed again, this time with some members being elected by civil society itself (a long desired wish by the sector). This achievement has, again, come under question under the new minister Julijana Bizjak Mlakar in 2014 and the issue is unresolved at the time of writing this text.

To date, therefore, the structured dialogue still persists (in both dialogue groups: for NGOs and self-employed in culture), revolving around key issues of financing of NGO organisations and the self-employed, changes to the Act Regulating the Realisation of the Public Interest in the Field of Culture, public tendering procedures and other strategic documents and measures addressing the NGO sector and self-employed in culture and cultural sector in general.

Last update: December, 2014

Responsibility for culture is divided among several governmental authorities. The main authority in charge of culture is the Ministry of Culture, which is also responsible for the media. Other ministries responsible for certain areas of cultural affairs include:

- The Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, responsible for cultural and arts education in schools, for education in different cultural vocations at upper secondary and tertiary levels and for music schools;

- The Ministry of Economic Development and Technology houses the Slovenian Intellectual Property Office;

- The Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning plays an important role in the concept of the integrated conservation of cultural heritage and the cultural landscape through planning;

- The Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities is responsible for co-financing conservation, restoration and erection of monuments and memorials to the victims of war;

- The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food is active in the protection of the cultural landscape and the development of rural areas (cultural tourism and rural cultural heritage conservation);

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is in charge of drafting and concluding international umbrella agreements in the fields of culture, education, and science and the related inter-governmental protocols;

- The Office for Slovenians Abroad, promoting cultural relations with the Slovene minority and emigrant organisations organising conferences, seminars, tenders, etc.

It must be explicitly mentioned that almost all ministries with different policies like public finances (national budget, rules for allocation of public money, tax regulation..), public administration (regulation of public servants and payment system), local self-government (local responsibilities for culture), interior affairs (visas, register of associations and foundations...), labour (working relations, pensions,..), social affairs (social cohesion issue, public works, unemployment benefit…) or the economy (the Slovene Enterprise Fund to help business investments of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have very strong implications for culture. Thus the Act Regulating the Realisation of the Public Interest in the Field of Culture 2002 explicitly states that other policies with implications for culture shall take cultural aspects into account. But the article has not yet been fully implemented in practise. According to this law the government, as a whole, is responsible for the National Programme for Culture, but in many ways this is still an aspiration. Neither the preparation of any existing strategic documents for the period 2004-2007, 2008-2011 and 2014-2017, nor the reports on their implementation, reflect any involvement of other ministries so far. The National Programme for Culture entirely preserves the sectoral nature of the document.

In some areas, it is usual to involve the Ministry of Culture in the process of the preparation of sectorial strategic documents that have a cultural dimension; for example, the Programme for Children and Youth 2006-2016, Resolution of the National Development Projects 2007-2023 etc. In the last few years, some general mechanisms have also been introduced to facilitate co-operation among the different ministries in order to develop a more holistic approach to policy making. It was assumed that culture should be an important part of the Strategy for the Development of Slovenia 2014-2020 and its supporting documents (Partnership Agreement; Operational Programme for usage of EU Funds 2014-2020; Strategy of Smart Specialisation). Yet culture is constantly being pushed outside of these documents despite attempts of (mostly) the NGO sector for culture to be included more broadly. The NGO sector even formed its own discussion groups under the guidance of CNVOS (Centre for Information Service, Co-operation and Development of NGOs), nevertheless the fate of culture in those documents remains highly uncertain and prospects are not good.

Cooperation between the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning and the Office of the Slovenian National Commission for UNESCO at the Ministry of Education, Science and Sports has been recognised as crucial for the implementation of the international conventions for the protection of cultural heritage and valuable natural features in the Republic of Slovenia. At first the adoption of a common strategy was envisaged by the National Programme for Culture 2008-2011 but it has not been realised. Therefore the current National Programme for Culture 2014-2017 postponed its adoption until 2015.

Last update: December, 2014

Re-allocation of public responsibilities such as privatisation or outsourcing of activities hasn't occurred in practise yet. However, a new Public-Private Partnership Act (Official Gazette No. 127/06), 2007, has provisions for public institutions offering public-private partnerships as a credible alternative to privatisation. Unlike in the case of privatisation where government gives up its control, the private-public partnership means shared risks as well as shared benefits. The sharing of responsibility between the public sector, non-profit civic sector and for-profit business sector is possible if cooperation goes along the line of their different interests. PPP is basically just a different method of procuring public services and infrastructure by combining the best of the public and private sectors with an emphasis on value for money and delivering quality public services. Until now, no long-term contract under which a public body allows a private-sector enterprise to participate, with or without a financial contribution, in designing, constructing and operating a public work has been realised. Nevertheless it has been reported that the first pilot cases are emerging in different fields, mainly digitalisation (e.g. national archive, national library). Most of these cases are based on the role of the private partner as an investor providing much needed technological infrastructure and the role of the public partner providing access to the material. Business models are mostly based, or are expected to be based, on joint exploitation of digitalised content.

Last update: December, 2014

Table 21: Cultural institutions financed by public authorities, by domain, various years

| Domain | Cultural institutions (subdomains) | Number (Year) | Trend (++ to --) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage sites (recognized) | 300 (of national importance); 7 975 (of local importance); year: 2013 | |

| Museums (organisations) | 31 (2009) | ||

| Archives (of public authorities) | 7 (2009) | 0 | |

| Visual arts | Public art galleries / exhibition halls | 121 (2012; included are NGOs) | - |

| Art academies (or universities) | 2 (2013) | + | |

| Performing arts | Symphonic orchestras | 3 (2013) | + |

| Music schools | 64 (2013) | ||

|

Music / theatre academies (or universities) | 2 (2013) | 0 | |

| Dramatic theatre | 12 (2013) | 0 | |

| Music theatres, opera houses | 2 (2013) | 0 | |

| Dance and ballet companies | 2 (2013) | - | |

| Books and Libraries | Libraries | 1 090 (2009) | |

| Audio-visual | Broadcasting organisations | 1 (2013) | 0 |

| Interdisciplinary | Socio-cultural centres / cultural houses | 64 (2013) |

Source(s): SORS; Ministry of Culture RS; http://www.dijaski.net/studij/seznam-visokih-sol-v-sloveniji.html; http://www.mizs.gov.si/si/delovna_podrocja/direktorat_za_predsolsko_vzgojo_in_osnovno_solstvo/glasbeno_izobrazevanje/seznam_glasbenih_sol/

Last update: December, 2014

The modernisation of the public sector in culture has been a declared priority for many years but until now nothing substantial has happened in this regard. To date, there are few inspiring examples of successful collaboration between culture and business. Some events have attracted considerable private funds (e.g. festivals) and are the first step in creating an environment for co-operation. There are some examples of "good practice" in this area such as the regional cultural centre "Festival Seviqc Brežice" dedicated to making the early music experience available to the wider public. In 2007 it attracted almost 40% of its turnover through innovative models of cooperation, donations and sponsorship. Logically, the business model in 2014 had to be adjusted to the changed business environment (with smaller pronouncement on private funds) yet it remained innovatively oriented in its marketing strategy, combining national and local public and private financing, the latter contributing to the lower price of the tickets (as announced in the business plan of 2014) and receiving specially designed sponsor packages (Source: http://www.seviqc-brezice.si/index.php/za-sponzorje/). Considering its non-commercial orientation, the invention of new forms is based on the personal activism of the leading figure of this festival. His work inspires artists, business people, diplomats and local leaders.

Another interesting example is the regional cultural centre "Narodni dom Maribor" with its most successful project, a two-week long multicultural Summer Festival Lent which mostly takes place at several different open-air stages, along the riverbank, south of the old city centre. In 2007, it attracted not only an incredible concentration of cultural events (402) and around 500 000 visitors, but also the greatest number of sponsors that contributed 80% of the festival budget (2 million EUR). Similary as with Festival Seviqc, the changed business environment due to the financial crisis changed also the responsiveness of private sponsors. Nevertheless, in 2014 they managed to attract approximately the same number of visitors as in 2007 (about 500 000) and organised even a significantly higher number of events (486) Source: http://www.festival-lent.si/info/statistika/.

This successful festival formula comprises classical concerts, ballet performances, jazz concerts with jam sessions, singer-songwriter concerts, chansons and ethno-music concerts, folklore evenings, street-theatre performances, and performances for children, called "Children's Lent", and, finally sports events. It raises the profile of the second biggest city in Slovenia and reflects the regional pride in having the biggest festival in the country.

The biggest cultural centre in Slovenia, Cankarjev dom (CD), both a cultural and congress centre. In its cultural operation it presents, produces, co-produces, organises and provides cultural and artistic events, state ceremonies, exhibitions and festivals. Since CD is mostly a cultural centre, over two thirds of the available halls are annually reserved for culture and the arts. Nevertheless due to its key role as a central Slovene congress centre with the highest number of international congresses and a mobile group of professional congress organisers in other Slovene congress venues, it contributes more than 20% to the cultural budget. Taking into account sponsorship and marketing of cultural events (public funds participate less than 60% of its turnover in 2013. Cankarjev dom is not an example of private public partnership, but a successful mixture of cultural and congress activities with the latter as a factor in its financial sustainability (Source: http://www.cd-cc.si/sl/katalog-informacij-javnega-znacaja/, http://www.cd-cc.si/media/PoslovnoPorociloCD2013.pdf).

Last update: December, 2014

The Slovene Chairmanship of the Council of Ministers of Culture of South-East Europe (CoMoCoSEE) in 2013 worked towards enhancing the role of culture and cultural heritage for sustainable development in modern societies of the region, thus strengthening the relevance of this regional forum in Europe also beyond its borders. The CoMoCoSEE Brdo Declaration (9 April 2013), concluding the Slovene Chairmanship, particularly acknowledged the important role of cultural and arts education in fostering cultural awareness and expression, creativity and diversity, as well as contributing to human development, socio-cultural well-being and social cohesion, and stated the development of arts and cultural education as one of the priorities of our regional cooperation. On the occasion of the 2013 CoMoCoSEE ministerial meeting in Slovenia, an important travelling exhibition "Imagining the Balkans"uniquely bringing together national museums from the region in their common historic narrative was opened under UNESCO patronage. Furthermore, the strategy of regional cooperation for 2014-2015 adopted at the following CoMoCoSEE ministerial meeting in June 2014, Ohrid, Macedonia, listed specific priority areas: effective and sustainable management of cultural heritage; fighting the illicit trafficking of cultural property and promoting the restitution of illicitly trafficked exported or imported property; safeguarding intangible cultural heritage; fostering creativity and the diversity of cultural expressions; and development of cultural and arts education in the region.

The Slovenian Culture and Information Centre in Austria (SKICA), established in Vienna in 2011 as a unit of the Embassy of the Republic of Slovenia, is the only cultural institution of the Republic of Slovenia abroad. It is a joint project of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Culture. The centre aims to integrate Slovene creativity in the field of arts and culture into the cultural milieu of the city of Vienna and beyond. SKICA aims to become a model for the future network of Slovene culture and information centres abroad. The SKICA page links to other pages on Slovenian culture at home and worldwide and functions as a gateway of information on Slovenia for foreigners.

Another permanent structure is the Forum of Slavic Cultures (FSC). It undertakes a diversity of projects intended to stimulate common research in culture and the arts; translation projects are also undertaken to establish and strengthen collaboration in linguistics and Slavic studies. They focus primarily on literature, linguistics, translation, ethnography, museology, folklore and archival studies, education, theatre and music. The FSC cooperates with more than 20 countries across the globe and is open to new partnerships. One long-term project of the Forum of Slavic Cultures is "100 Slavic Novels", led by the Slovenian Writers Association, which is one of the oldest projects undertaken. Each of the Slavic countries involved selects 10 authors, whose novels will be translated into the other relevant Slavic languages and published in the respective countries. Other FSC projects are: international exhibition of Slavic Capitals in 2D; Craftattract Project focusing on the registration of traditional crafts and on their potential to attract cultural tourism; The Best of Slavic Heritage to stimulate and improve cooperation among the museums and galleries of the participating countries; Musical Bridges creating a network of young musicians which gives young Slavic musicians better mutual knowledge, greater recognisability, and easier access to the public.

The Ministry of Culture has annual or biennial calls for international presentations of art, to be presented at fairs and festivals. It also supports international events in Slovenia such as the Biennial of Graphic Arts, BIO, the Biennial of Industrial Design, the Forma Viva Open Air Sculpture Collection in Maribor, and the European Triennial of Slovene Small Sculpture. International platforms in the field of contemporary dance and theatre are also supported. Since 2003, the mobility of artists is supported through working stipends, competitions and awards, and residency schemes which are announced annually. One is open to creators to bid for short-term residencies in apartments owned by the Ministry in New York City, Berlin, London and, since 2011, also in Vienna. Another determines the operator of the Creative Europe Desk and the international cooperation portal Culture.si. Other calls are for the organisers / curators of the Venice Biennale and Venice Biennale of Architecture. The gallery space A+A, which was established in Madrid in the 1990s and ten years later transferred to Venice, was closed in 2014 due to other priorities.

The Division for International Cultural Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is also responsible for umbrella agreements in the field of culture, education and science and their programmes. There are 47 international umbrella agreements on culture, education and science, currently signed by the Republic of Slovenia. The international umbrella agreements are generally enabling bilateral contacts in the field of scholarship exchanges, exchanges in the field of art and culture and introducing individuals to the languages and civilisations of other states. According to the new strategy, the umbrella agreements are relevant for cultural cooperation with countries where these kinds of documents still pave a way to better interaction with countries such as Russia, China and other non-European countries. The agreements will probably no longer be signed with EU member states; although neighbouring states are an exception.

The funds for supporting cultural cooperation at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs have been reduced in the last few years. International cultural cooperation is considered to be a part of the regular activities of cultural institutions and thus included in their regular public funding. This division makes it difficult to determine a total figure for expenditure in this field in Slovenia. According to the Table below given by the Ministry it is understood there have been budgetary reductions for culture in external relations.

Table 1: Budgetary allocations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to cultural cooperation in EUR, 2011-2014

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membership fees | 40 521 | 32 404 | 30 608 | 32 417 |

| International Cooperation | 831 318 | 601 507 | 589 771 | 579 670 |

| Forum of Slavic Cultures | 153 000 | 122 400 | 122 400 | 114 793 |

| Total | 1 024 839 | 756 311 | 742 779 | 726 880 |

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Last update: December, 2014

Slovenia takes an active part in international organisations (UNESCO, Council of Europe, and the EU) and is also closely involved in multilateral and regional associations and initiatives, such as the Central European Initiative, the Quadrilateral (Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary), the Adriatic-Ionian Initiative, the Central European Cultural Platform, the Alps-Adriatic Working Group, etc. Slovenia joined both the Anna Lindh Foundation and ASEF (Asian Europe Foundation). Slovenia hopes for better representation of its culture and cultural heritage in different international programmes and projects. The expected accession to the OECD represents an opportunity to improve cultural statistics in Slovenia.

The Institute for Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia (ZVKD) participates by preparing dossiers for nominations to the list of UNESCO world cultural and natural heritage (in 2011 the Prehistoric Crannogs around the Alps have been included on the UNESCO list as a transnational nomination of Switzerland, Austria, France, Germany, Italy and Slovenia).

ZVKD also participates by preparation of arguments for the ceremony of the Mark of European Heritage of the EU and by activities of the heritage network HEREIN of the European Council and international non-profit organisation HEREIN AISBL founded mostly for support to heritage management, dissemination of information on policies of heritage maintenance and international cooperation.

The Republic of Slovenia is a partner in the Forum for Slavic Cultures. The goal of the Forum is to promote the development of cultural cooperation among all countries whose populations speak Slavic languages. The Forum can contribute to better understanding of the cultures of participating countries, through the exchange of information and knowledge and the direct dissemination of both these issues to the public, especially in the domains of language, literature, culture and art, education and communications. One of the most important plans is the publication of 100 Slavic novels. The Forum for Slavic Cultures could also facilitate the implementation of bilateral cultural agreements and programmes concluded between the participating countries.

The Ministry of Culture is responsible for implementing and monitoring the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. The importance of discussions carried out at UNESCO, with a view to adopting an international convention on the protection and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions, was also stressed within ASEM / ASEF dialogue and especially at the conference "New Models, New Paradigms – Culture in EU External Relations" organised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of the events surrounding the Slovene presidency of the EU Council.

Last update: December, 2014

Slovene museums, archives and libraries are members of various international or foreign organisations and participate in their work. International activities of the Slovene museums, archives and libraries take the form of co-operation in various international projects, membership of international associations, organisation of exhibitions, international conferences and seminars, and development of various forms of professional training. For the public sector, the bilateral agreements on international cultural co-operation with most European countries present an important generator of the development of various forms of professional training and collaboration. All these international activities are a regular part of the operation of the public institutions that get public funding within their regular annual budgets. The new models and forms that are increasingly present in the non-institutional sector depend mostly on project funding, domestic as well as international.

The Mini Theatre (puppet / theatre), the Študentska založba Publishing House(one of the most productive Slovene publishing houses),the Exodos Institute (a non-profit, independent theatre and dance production centre), and Projekt Atol (a non-profit cultural institution founded in 1990s by the Slovene conceptual and new media artist Marko Peljhan) place great importance on international cooperation, as they produce performances, tour abroad and host foreign artists or performances in Slovenia.

They are / were recipients of funding from the European Commission's Culture Programme, i.e. Mini Theatre (http://www.mini-teater.si) for "Puppet Nomad Academy I, II, III" (in 2009, 2011, 2012), the Študentska založba Publishing House (http://www.studentskazalozba.si) for translation projects in 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, as well as for the "Days of Poetry and Wine Festival" (2008, 2010) and "Poetry Re-Generation" project (in 2012, http://www.poezijainvino.org), the Exodos Institute (http://www.exodos.si) for the "Exodos International Festival of Contemporary Performing Arts", biennial since 2011 (in 2010), and Projekt Atol (makrolab.ljudmila.org) for the "IMMEDIATE: Immersive Media Dance Integrating in Telematic Environments" project (in 2007).

The Mini Theatre's activity, including the adaptation of one of its venues, was supported by a grant through the EEA Financial Mechanism and the Norway Financial Mechanism in 2008–2009.

The Exodos Institute is a member of the IETM – International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts, Festivals in Transition (FIT), European Dance Education Network (DANCE) and the Trans Danse Europe network of production houses. The Projekt Atol Institute is a partner to the following initiatives: Arctic Perspective Initiative (API), world-information.org (WIO), the MIR network (Arts Catalyst, Leonardo / Olats, V2, and Multimedia Complex of Actual Arts), Acoustic Space Lab, and AUVSI.

In 2010 the Študentska založba Publishing House produced the "Fabula Festival of Stories" as part of World Book Capital Ljubljana 2010, while Exodos collaborated with a project involving the creation of a "Labyrinth of Art", a living space for walking and contemplation on the outer edge of Ljubljana.

The Flota Institute is a non-profit cultural institution for the organisation and realisation of cultural events, established in 2001 by the dancer and choreographer Matjaž Farič. In 2006, the Institute started organising the "Front@ Contemporary Dance Festival" (http://www.flota.si/fronta.html) in Murska Sobota (http://www.murska-sobota.si), which has 13 000 inhabitants and is situated near the border with Austria, Croatia and Hungary. The event is aimed at audiences in the area between Maribor, Budapest, Zagreb and Graz, who would not normally have access to cutting-edge contemporary dance performances. The festival was supported by the Ministry of Culture (80%), the Municipality of Murska Sobota (4%), sponsors and donors (6%) and its own funds and income (10%).

In order to achieve the stated objectives, the Flota Institute extended its operation to the area of neighbouring countries, connected with local organisations and spread events evenly throughout the year. Thus Front@ Festival became the focal point of international integration in the project "Dance Explorations Beyond Front@" (http://www.flota.si/network/network.html) wherein five organisations from Slovenia, Austria, Hungary and Croatia participated in the years 2008-2010. The central part of the festival programme still consists of events resulting in international integration. In 2010, the festival was supported by the Ministry of Culture (50%), the EU Culture Programme in the context of Beyond Front@ (25%), the European Cultural Foundation in the context of Beyond Front@ (8.3%), the Municipality of Murska Sobota (2.8%), sponsors and donors (4%) and its own funds and income (9.8%).

In 2012, the Flota Institute with its partners ushered in a new phase of a two-year international collaboration entitled "Bridging New Territories" (http://www.beyondfronta.eu/). The project’s partners were the Greenwich Dance Agency (UK), Verein für neue Tanzformen and Offenes haus Oberwart (Austria), Pro progressione (Hungary) and the Hrvatski Institut za pokret i ples (Croatia). The project also involved "bridge" partners from Austria, Slovenia, Slovakia, Serbia, Portugal and Italy.

In 2012, the Front@ Festival was supported by the Ministry of Culture (28.1%), the EU Culture Programme in the context of Beyond Front@ (9.8%), the European Capital of Culture (ECOC) Maribor 2012 (29.5%), the Municipality of Murska Sobota in the context of ECOC (29.5%), and its own funds and income (2.9%).

Founded in 1996, KIBLA, Association for Culture and Education (http://www.kibla.org), works in the field of contemporary culture and art, information technologies, interdisciplinarity and education. KIBLA offers free access to internet and cultural goods. At the time of its formation, modern technology was not a widely accessible commodity in Slovenia. KIBLA was a pioneer in connecting the Slovenian cultural sphere globally with new technologies, and consequently enriched the field by bringing fresh possibilities for expression, communication and integration. KIBLA's activities include: two cyber-spaces (KIBLA and KIT), KiBela gallery, KIBLIX open source festival, "Days of Curiosity" educational festival, the experimental Digital community (I.-VIII), "Za:misel" bookstore literature and the mobile "Festival of Love" in local castles, desktop publishing in cooperation with TOX publishing, Folio magazine, improvised music "Skrite note" and "Izzven", DANES microtonal music and the electro-acoustic MED festival, and Romany programmes. A number of international projects like Mediaterra, TRG, txOm, E-Agora, Patent, EMMA, Travel in Europe, Robots and avatars, etc. form an outline of KIBLA's cultural policy over the last decade – in terms of interdisciplinarity, networking and integration. Since its foundation in 2004, KIBLA has been a part of the Multimedia Centre’s network of Slovenia. In 2008 it received an excellency award in the field of multimedia, awarded by the European multimedia forum. Soft Control (2012–2015) is KIBLA's international coordination project – a link between western and eastern-European partners working in the field of arts, sciences and contemporary technologies with institutes from the USA, Australia, Singapore, Japan, Russia, and Canada; and a continuation of an interdisciplinary direction set by two other coordination projects, the X-OP (2008–2011), an exchange of art producers and operators, and Hallerstein (2008–2009), which created a link between the Chinese and European cultural spaces. Participating in former European capitals of culture – Cork 2005 and Sibiu 2007 – set the foundation for preparing the Candidature for ECOC Maribor 2012 (2006–2008), and further collaborations: ECOC Istanbul 2009, Turku 2011, Maribor and Guimarães 2012; KIBLA also supports Belgrade 2020.

The Bunker Institute (http://www.bunker.si) acts in the performing arts scene at transnational level, which has been active internationally since its formation in 1997. One of Bunker’s biggest projects is the annual "International Festival Mladi Levi", celebrating its 15th edition in 2012, and which brings up to 15 foreign groups to Slovenia, ranging from emerging young artists to those already well-established. In 2011 the Festival was supported by the EU Culture Programme.

The Bunker Institute is a member of the following international networks: IETM, wherein eleven members of the network got together and established a new network called Imagine 2020 – Arts and Climate Change (http://www.imagine2020.eu), which deals with the challenging issues of climate change in connection to arts and culture. The network has been supported by the EU Culture Programme two consecutive times, in 2008 as "2020 Network – Thin Ice" and in 2010 as "Imagine 2020 – Arts and Climate Change". The latter has also supported a performance of the Betontanc group, an artistic company that is produced by the Bunker Institute since 1997. The performance was a result of international co-productions / residencies with a Japanese artistic group The Original Tempo. The premiere showing to place in the frame of ECOC Maribor 2012. The Sostenuto network (that has been supported as a project by the European Regional Development Fund in 2009–2012) aims at reinforcing the competitiveness and the capacities of economic and social innovation from the cultural and creative sector in the Med space by accompanying its transformation towards new economic and social models. One of the outcomes of the project in Slovenia is the establishment of the Association Cultural Quarter Tabor, which connects cultural organisations in Ljubljana's city quarter Tabor, where the Bunker Institute is also based. In 2002, the Bunker Institute, together with CUMA (Istanbul), IETM, Expeditio (Kotor) and AltArt (Cluj), established an informal network Balkan Express, which aims to encourage collaboration within the Balkan region. In 2012 the Network focused its mission on developing a platform for discussion and sharing knowledge and experiences, re-thinking the role of arts in today's ever changing society. The network was supported by the ECF.

In 2012 the Bunker Institute (with its "Festival Drugajanje" in Maribor) connected with European partner organisations, i.e. Spielmotor München e.V. / SPIELART Festival (Munich), Baltic Circle International Festival / Q-theatre (Helsinki), New Theatre Institute of Latvia / Festival HOMO NOVUS (Riga), MTÜ Teine Tants, August Dance Festival (Tallinn), LIFT – London International Festival of Theatre (London), Stichting Huis en Festival a/d Werf (Utrecht), which organises their own festivals, forming a project called "GLOBAL CITY – LOCAL CITY (GL-CL)" for the artistic exploration of social, ecological, and political realities, and civic and social potential in individual city quarters and of global city developments of the cities of participating theatre and dance festivals. In 2012 the project was supported by the EU Culture Programme.

Additional resources:

Mobility trends and case studies

Examples of mobility schemes for artists and cultural professionals in Slovenia