1. Cultural policy system

Spain

Last update: February, 2019

Objectives: The main objectives of cultural policies implemented by any level of the Spanish public administration are the preservation of cultural heritage and the promotion of access to culture. The differences arise in what is considered cultural heritage (tangible versus intangible; of the state versus identities) and which types of cultural manifestations should be promoted and how access should be granted and financed. If we analyse recent cultural policies in terms of the cultural policy principles defined by the Council of Europe, we see that promotion of national identity -- the main vehicle for articulating cultural policy in the regions, particularly in those having separate language environments -- has been exacerbated in the last years. In terms of recognising diversity, the very way the Spanish state is organised territorially has been an admission of the cultural diversity of the country. Protection of diversity has been mainly interpreted by looking internally at the individual traits of the various cultures comprising modern-day Spain. Since 2000, as a result of the dramatic increase in immigration, recognition of another form of cultural diversity beyond national borders was included in the cultural policy agendas, as part of the social integration of immigrant groups. Support for cultural creativity has been traditionally articulated as an aim of cultural policy along three main axes: statutory protection of intellectual property; the teaching of creative arts; and specific measures to promote the work of creative artists themselves. Access to culture and participation in cultural life are among the prime objectives of recent Spanish cultural policy. However, generating demand outside the sphere of mass culture turned out to be a complex issue. Equally, the democratisation of culture, understood as the citizens' right to have their say about how the cultural life of their communities is defined, leaves considerable room for development in the search for a fully rounded Spanish cultural policy. Main features: Spanish cultural policy has undergone profound and rapid changes since 1977. The cultural model of the democratic period has combined the recognition of cultural pluralism, the determination of the state to foster culture and a massive decentralisation of administrative tools, in accordance with the rules for the territorial government laid down in the Constitution of 1978.[1] This model has also tried to favour an increase in the involvement of private companies and civil society in running the country's culture. The relevance of one characteristic or another has depended on the political party in office and its relationships with regional governments. For instance, the role of public policies during the last decade has experienced profound changes in recent years, as a result of the economic crisis and of the re-centralising tendencies of the Popular Party's government. Traditionally, the decentralised Spanish policy has favoured the adoption of different models for cultural management and for the support and promotion of artistic creation, though much of the funding is ultimately linked to public budgets. Thus, the economic and operational autonomy of the institutions could be somehow limited. Sometimes, the creation of arms-length bodies has been encouraged; sometimes, advisory councils have tried to connect cultural policy with relevant cultural stakeholders. In this sense, the National Council for Culture and the Arts in Catalonia is a hybrid institution, an arms-length body that was the first instrument of its kind in the Spanish state. It was created by the 6/2008 Act with the main objectives of ensuring the development of cultural activity and collaborating in drawing up both specific cultural policy and policy that supports and promotes artistic and cultural creation. The council was reformed in 2011, and it was given a new structure and configuration that sought to reinforce its supervision and advisory role for public cultural policies, while losing many of its executive functions (11/2011 Act of restructuring of the public sector). Since 2000, the Community of the Basque Country has an advisory collegial body of participation, cooperation and advice in the field of culture, attached to the relevant department in the field of culture of the Basque government (Decree 27/2008 that modifies the Decree 219/2000). In the same vein, the Andalusian Agency of Cultural Institutions (Act 1/2011 and Decree 103/2011) was created in 2011 by merging some previous arms-length institutions. It is attached to the regional cultural department and has wide functions in the management, programming and promotion of cultural programmes. One year later, the autonomous community of Castile-Leon created the Council for Cultural Policies (Decree 26/2012) as a regional organ of participation, consultation, analysis and coordination in the field of culture, arts and cultural heritage.Background

1939-1975: The official culture of Francoism combined fervent nationalism with equally fervent Catholicism. Its artistic predilection was for traditional styles. From the 1960s onwards, rigid press and education policies began to soften. 1977-1982: In 1977, the Ministry of Culture was established and by means of international exhibitions, congresses, prizes and appointments, much of the cultural heritage silenced by Francoism was recovered, and the work of exiled artists and intellectuals recognised. The Constitution of 1978 and the charters of regional autonomy set up under its aegis, initiated a period of freedom of the press and artistic expression, combined with greater state activity in disseminating culture and giving full recognition to the cultural and linguistic diversity of Spain. 1982-1996: Different Socialist governments stressed the need for the state to be present in those areas where private initiative was likely to be lacking. In the initial phase, up to 1986, the central goal was to preserve the much-deteriorated historic and artistic heritage, renovate theatres and auditoriums, and subsidise artistic expression. It was found that the political aims and the gradual transfer of responsibilities to the regional authorities required that the Ministry be slimmed down and reorganised. In a second phase, from 1986 to 1996, the authorities staged a series of events that brought their cultural policies to the foreground of public attention. These were years of exuberant artistic activity and freedom of expression, in which Spanish artists brandished a dizzying array of political and cultural banners while their international colleagues were welcomed to join in. This cultural explosion coincided with, and to a certain extent masked, the lack of real resources. The decentralised structure of government often succeeded in recovering and strengthening regional cultural diversity but did not always bring about a broader participation in cultural events or improve the standards of artistic creation. 1996-2004: Under the liberal-conservative government of the Popular Party, the broad outlines of ministerial action remained the same: protection and dissemination of Spain's historic heritage; management of the great national museums, archives and libraries, and promotion and dissemination of film, theatre, dance and music. The deregulatory tendency of the Popular Party's government led to efforts to involve the private sector in major cultural initiatives. 2004-2011: The Socialist Party restructured the departments of the Ministry of Culture on different occasions and made the cultural industries one of its main priorities. The economic crisis also had its effects on culture, resulting in a reorganisation of the Ministry of Culture and austere budgets as a key way of reducing the public deficit. 2011- June 2018: Besides structural changes and cuts in public budgets, culture and education were two of the subjects that caused greater disagreement between the central government (led by the Popular Party), the Autonomous Communities (in particular those with their own language) and the creative sector. [1] Prieto de Pedro, J (2004) Cultura, culturas y Constitución. Editorial Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. Madrid (second edition).Last update: February, 2019

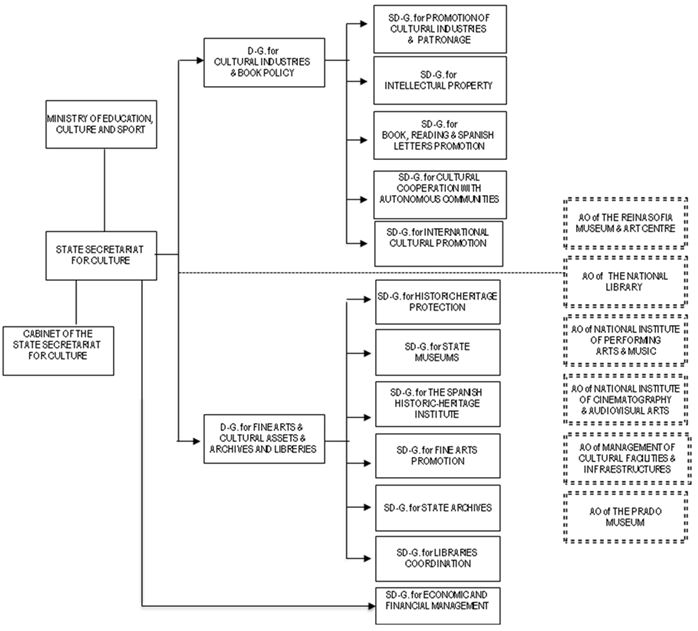

Central level – Ministry of Culture and Sport

DG: Directorate-General

SD-G: Sub Directorate-General

AO: Autonomous Organisation (self-governing public bodies dependent on the Ministry, in which its director has the rank of General Director)

Regional Level - Autonomous Communities

|

AUTONOMOUS GOVERNMENT |

DEPARTMENT |

VICE DEPARTMENT |

DIRECTORATES |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ANDALUSIA |

Culture and Historic Heritage |

Vice Department of Culture

|

General Secretariat of Cultural Heritage General Secretariat of Cultural Innovation and Museums |

|

ARAGON |

Education, Culture and Sport |

|

Secretariat for Technical Affairs D-G. for Culture and Heritage |

|

ASTURIAS |

Education and Culture |

Vice Department of Culture and Sport |

Secretariat for Technical Affairs D-G. for Cultural Heritage |

|

BALEARICS |

Culture, Participation and Sports |

|

General Secretariat D-G. for Culture |

|

CANARIAS |

Tourism, Culture and Sports |

Vice Department of Culture and Sports |

Secretariat for Technical Affairs D-G. for Culture |

|

CANTABRIA |

Education, Culture, and Sport |

|

General Secretariat for Education, Culture, and Sport D-G. for Culture |

|

CASTILE-LEON |

Culture and Tourism |

|

General Secretariat for Culture and Tourism D-G. for Cultural Heritage |

|

CASTILE-LA MANCHA |

Education, Culture and Sports |

Vice Department of Culture |

General Secretariat for Education, Culture, and Sport |

|

CATALONIA |

Culture |

|

General Secretariat for Culture D-G. for Cultural Cooperation |

|

CEUTA* |

Education and Culture |

|

D-G. for Education and Culture |

|

VALENCIAN COMMUNITY |

Education, Research, Culture and Sport |

Secretary for Culture and Sport |

Secretariat Sub-Secretariat |

|

EXTREMADURA |

Culture and Equality |

|

General Secretariat |

|

GALICIA |

Culture, Education and University Planning |

General Secretariat for Culture General Secretariat for Linguistic Policy |

Secretariat for Culture and Sport D-G. for Cultural Heritage |

|

LA RIOJA |

Economic Development and Innovation |

|

Secretariat for Technical Affairs |

|

MADRID |

Culture, Tourism and Sports |

Vice Department of Culture, Tourism and Sports |

Secretariat for Technical Affairs D-G. for Cultural Heritage D-G. for Cultural Promotion |

|

MELILLA* |

Culture and Celebrations |

Vice Department of Celebrations |

D-G. for Culture and Celebrations |

|

MURCIA |

Culture, Tourism and Environment |

|

General Secretariat |

|

NAVARRE |

Culture, Sport and Youth |

|

D-G. for Culture - Príncipe de Viana Institution |

|

BASQUE COUNTRY |

Cultural and Linguistic Policy |

Vice Department of Culture |

Directorate for Cultural Heritage |

Source: Ministry of Culture and Sport

* Cities with autonomous status

Last update: February, 2019

The 1978 Constitution created a new administrative territorial division in Spain, with three administrative levels: central government, Autonomous Communities or Regions and local councils (municipalities and provinces). According to the areas of competence laid down in the Constitution, all three levels have general responsibilities for culture, although the majority of public cultural expenditure comes from regional and local governments, which together represent 86% of public cultural spending (see chapter 7.1.2).

The central government holds the exclusive responsibility for protecting cultural property against export, creating legislation to protect copyright, overseeing the basic rules on freedom of expression, creation and communication and regulating the means of communication (radio, television and the press) solely to the extent that such freedoms are threatened. At the same time, it retains the ownership of certain major cultural institutions, such as some museums, archives and libraries, even if their administration is sometimes delegated to the regions.

The rise to power of the Socialist Party (June 2018) established a new structure of the Ministry of Culture and Sport (Royal Decree 817/2018) with three Directorates General:

- Directorate-General for Books and Promotion of Reading

- Directorate-General for Fine Arts

- Directorate-General for Cultural Industries and Cooperation.

This lean organisational structure is also due to the fact that some cultural bodies (autonomous organisms) have an independent legal status (legal entities of public law) and a certain degree of operating autonomy. Such is the case for e.g., the Prado Museum, the National Library of Spain, and the Film and Audiovisual Arts Institute.

Last update: February, 2019

At the regional level, Spain is divided into seventeen Autonomous Communities (and two cities with autonomous status), which have broad powers in matters of culture. In particular, the Constitution gives them both managing and normative control over those areas where public regulation of some kind is traditional: museums, libraries, performing arts, handcrafts, etc. National museums, libraries and archives remain under state control, although, in most cases, responsibility for operating them is delegated to the regions.

The involvement of regional governments in cultural matters has been traditionally greater in those communities that have their own language and in the so-called "historic nationalities", i.e., those that first obtained administrative autonomy: Andalusia, Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia (article 151 of the 1978 Spanish Constitution). At present, only Andalusia and Catalonia have assigned the administration of cultural affairs to a specific Department, while the remaining regional governments have opted for mixed bodies in which culture is administered jointly with education, tourism, linguistic policy, innovation and / or sports.

The regions have been very active in caring for their heritage and building cultural infrastructures. In those regions with their own language, much cultural activity is directed at recovering and developing the sense of regional identity, particularly by means of statutory initiatives to protect these languages.

Similar to national cultural administration, regional cultural administrations have lightweight structures. The coexistence of administrative structures with autonomous organisms is also present in various regions that have autonomous bodies in their departmental structures, e.g.:

- regional policy on reading and literature promotion is entrusted to an autonomous government body, the Institute of Catalan Literature;

- in Andalusia, the management of cultural programmes is entrusted to the Andalusian Agency for Cultural Institutions, constituted as an entity of public law;

- Galicia has the Galician Cultural Industries Agency and the Galician Centre of Contemporary Art;

- Castile-Leon has a Council for Cultural Policies with an advisory character that informs about the state of culture, the arts and cultural heritage in the community;

- regional policy for the promotion, development, protection and dissemination of the arts and cultural industries in Murcia is entrusted to the Institute for Cultural Industries and the Arts; and

- the Valencian Community entrusted the development and implementation of cultural policy to the entity CulturArts Generalitat, which is governed by private law.

Last update: February, 2019

At the local level, the Local Regime Act 1985 gave city and town councils administrative powers over local heritage, cultural activities and amenities, and "leisure activities". The law states that population centres of over 5 000 inhabitants are obliged to provide library services, and it allows the municipalities to promote "complementary activities to those provided by other government bodies and, in particular, those concerning culture". In practice, local authorities have almost unlimited power to promote cultural activities at the municipal level. Their proximity to the citizens and the political rewards of such activities explain the huge expansion of local cultural events up to the start of the 1990s. Today, the bulk of public cultural spending (over 50%) is carried out at the local level.

A distinction should be drawn between the bigger cities (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Valladolid, Bilbao, Seville, Oviedo, Salamanca, La Coruña, Santiago de Compostela), capable of funding major projects and activities, and the medium-sized and smaller towns, that only provide the basics (libraries) and support patron-saint festivals and other strictly local events.Last update: February, 2019

A key actor in the provision of cultural services is the non-profit sector, many times linked to big financial or industrial corporations. The financial crisis dramatically changed the funding of culture by the private sector, as many of the Cajas de Ahorro or saving banks disappeared. Still, institutions such as the Fundación Bancaria “la Caixa”, Fundación BBVA, Fundación Mapfre, or the Fundación Ramón Areces have their funding programmes for the promotion of culture and sometimes run their own cultural centres.

There are currently eight collecting societies authorised by the Spanish Ministry to be in charge of the management of usage and other asset rights, on behalf of and in the interest of several authors or other holders of intellectual property rights: the Spanish Society of Authors Composers and Publishers (SGAE), the Spanish Reproduction Rights Centre (CEDRO), the Association for the Management of Intellectual Rights (AGEDI), the Artists and Performers Society of Spain (AIE), the Visual Management Entity of Plastic Artists (VEGAP), the Audio-visual Producers' Rights Management Association (EGEDA), the Artists, Interprets, Management Society (AISGE), and the Audiovisual Media Author's Rights (DAMA).

Professional institutions work for the promotion of the cultural industries and safeguard author’s rights. Groups acting on issues related to artistic and cultural rights in recent years are for example:

- Spanish Association of Women Filmmakers and Audiovisual Media Professionals, founded in 2006, with the aim of promoting equal participation of women in the audiovisual media;

- Coalition of Creators and Content Industries, founded in 2008, with the aim to lobby for tightening of the intellectual property law and other measures against file sharing on P2P networks. It consists of several associations that are linked to authors and to the music and film industries in Spain;

the Spanish Federation of Associations of Cultural Managers, created late 1999, aims to unify the efforts of cultural management associations to address problems at state level, especially those related to the consolidation of the figure of the cultural manager and his or her social and professional recognition. It has developed two Pacts for Culture (in 2010 and 2015) aimed at influencing cultural policies based on the consensus of the professional sector.

Last update: February, 2019

With the aim of providing a cross-cutting element to the cultural field, there are a number of collegiate bodies in which different levels of the public administration or different areas of the same level cooperate. At present, the Sub-secretary of Culture and Sport (Royal Decree 817/2018) is responsible for overseeing inter-ministerial cooperation, particularly, with the Ministries of Industry, Trade and Tourism, Education and Vocational Training, Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation and Finance.

Traditional inter-ministerial cooperation initiatives include programmes such as "One Per Cent for Culture", referred to the financing generated by public works (at least 1% of their budget, updated to 1.5% in 2013) that has to finance works of conservation or enrichment of the Spanish cultural heritage or to enhance artistic creativity (Historical Heritage Act, 16/1985 Act). The programme is coordinated by an inter-ministerial Committee composed of the Ministry for Culture and Sport and the Ministry of Development, which undertakes joint actions that promote the conservation and enrichment of Spanish historical heritage.

There are also numerous and diverse inter-ministerial bodies and initiatives, for example:[1]

- In relation to the protection of underwater archaeological heritage, the Ministries of Defence and Culture drew up a general protocol to cooperate and coordinate the protection of underwater archaeological heritage.

- In order to provide full accessibility to spaces, cultural activities and services, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality presented the document A Comprehensive Strategy of culture for all.

- To combat infringements of intellectual property rights, an inter-sector Commission on Intellectual Property was set up, whose members are proposed by the Sub-Secretariat of the Ministries of Justice, Education, Culture and Sport, and Economy and Competitiveness.

In terms of intergovernmental co-operation, the State is constitutionally mandated to arrange for cultural communication among the different regions "in collaboration with them". To do so, the central government set up a specific unit today titled the Sub-Directorate General for Cultural Cooperation with the Autonomous Communities under the wing of the Directorate-General for Cultural Industries and Cooperation of the Ministry of Culture and Sport. The unit's task is to cooperate with the regions in their cultural programmes; to foster interregional communication in the area; to disseminate the wealth and range of the regions' cultural heritages; and to exchange information about cultural policies. It is also responsible for ensuring that the cultural diversity of Spain's regions is fully appreciated abroad, a task that the unit carries out in co-operation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, and Spanish embassies and consulates around the world.

In practice, the mechanisms for coordinating central and regional government activities on cultural matters have operated with different degrees of success. The Plenary session of the Sectoral Conference on Culture was held once in the third legislature (1986-1989), twice in the fourth (1989-1993) and the fifth (1993-1996) legislatures, not once in the sixth and the seventh (1996-2004), eight times in the eighth (2004-2008), nine times in the ninth (2008-2011), seven times in the tenth (December 2011- December 2015), not once in the eleventh (December 2015 – July 2016), once in the twelfth (July 2016 – June 2018), and not once in the recent legislature (from June 2018).

The Culture Plan 2020 of the State Secretariat for Culture, passed in 2017, incorporates, as one of its strategies related to the objective of promoting a social alliance for culture, the reinforcement of cultural cooperation with the Autonomous Communities. Among the specific measures, there is the impetus for the Sectoral Conference on Culture, for supra-regional cultural projects, and the circulation of good practices among territories.

Recovering and preserving the national heritage is the area where the combined action by the different levels of government has proven most fruitful. Since the beginning of the 1990s, there has been a proliferation of cooperation agreements at different levels of government mainly for major urban developments associated with the construction of prestigious cultural monuments / sites. One example is the Council of St. James, which was created in 2001 as a co-operation entity to facilitate communication between the central administration and the participating Autonomous Communities (Aragon, Asturias, the Basque Country, Cantabria, Castile-Leon, Catalonia, Galicia, La Rioja and Navarre).

Beyond the heritage field, within the framework of the Sectoral Conference of Culture, different working groups composed of representatives of the central administration and Autonomous Communities were established with the aim of promoting communication and cooperation in various aspects related to the cinematography and audiovisual, videogames, musical heritage and more.

As for relations among the regions themselves, the level of information and technical exchange is extremely low, with the exception of the historic communities. Collaboration between Catalonia and the Basque Country has materialised over the years in numerous projects and the exchange of information and experiences on their cultural policies. In late 2007, the Departments of Culture of those communities and of Galicia agreed to create a joint programme and to collaborate regularly in the following fields: cultural heritage, the arts, cultural industries and popular culture.

Similarly, very little progress has been made in inter-regional and national-regional co-ordination to project Spanish culture internationally. The notable exception has been the Ramon Llull Institute, a public body to promote Catalan language and culture abroad.

In terms of co-operation at the municipal level, aside from the abovementioned examples involving central and regional government and the councils of certain cities, mention should also be made of the assistance provided by certain regional governments for local townships. For example, the Island Councils of the Canaries and the Provincial Councils of some regions, mainly the Basque Country and Catalonia, have contributed to the development of inter-municipal cultural activities through museums, libraries, archives and local theatre tours. Municipal culture departments have also worked together with their colleagues responsible for urban development, education or tourism.

Since the Agenda 21 for Culture was approved on 8 May 2004, a growing number of Spanish cities and municipalities have adopted it at local government level. To promote the principles enshrined in the document, the United Cities and Local Governments established a Working Group on Culture, which is chaired by the Councillor for Culture of the Barcelona City Council. The Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces also has a Commission on Culture to provide local governments with useful planning and evaluation tools.

[1] Examples of agreements signed by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport during 2017 can be found here: http://www.mecd.gob.es/dms/mecd/portada-mecd/destacados-sin-pagina/Convenios-MECD-2017.pdf. And here for 2018: http://www.mecd.gob.es/dms/mecd/portada-mecd/destacados-sin-pagina/Convenios-MECD-2018.pdf.

Last update: February, 2019

Spain’s leading cultural institutions can be divided into three groups depending on their origins: national institutions, institutions set up by civil society, and institutions that emerged during the period of restored democracy. National institutions have been linked to the central government from the outset and most of them are in Madrid (Prado Museum, Royal Theatre, National Library of Spain, etc.). The second type can usually be traced to the cultural aspirations of the cultural elites at specific moments in history, particularly in those cities having a strong industrial base, for example, Barcelona, Bilbao, Oviedo, etc. Lastly, there are numerous public initiatives undertaken over the last 30 years by various levels of government, such as the construction of several major cultural spaces, the majority outside Madrid, thereby promoting cultural decentralisation. Some of those cultural facilities, promoted before the deep financial crisis without any feasibility study, remain inconclusive or without cultural activity.

National institutions depend nearly entirely on the central government for funding, although boards of governors are allowed considerable leeway in decision-making. A significant number of the other cultural institutions in the country are financed and self-managed under agreements between different levels of government. This inter-institutional co-operation seeks to promote coherence in regional development strategies and, indirectly, encourages greater self-management in the day-to-day running of the institutions.

Last update: February, 2019

Data on cultural institutions have been taken from the Cultural Statistics Yearbook published by the Ministry of Culture and Sport. Although it was not always possible to distinguish between public and private ownership, as shown in Table 1, the general trend in recent years has been the increase in cultural institutions. The most significant growth has occurred in privately owned scenic and stable spaces for theatre which increased by 20.6% in the period 2013-2017 (from 374 to 451). They were followed by publicly owned museums and museographic collections which grew by 9.5% (from 973 to 1 065) in the period 2013-2016, and scenic spaces for theatre which grew by 6.6% (from 1 110 to 1 183).

Table 1: Cultural institutions, by sector and domain

| Domain | Cultural institutions (sub-domains) | Public sector | Private sector | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (Year) | Trend last 5 years (%) | Number (Year) | Trend last 5 years (%) | ||

| Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage sites (historical) * | 391 (2013) 514 (2017) | 31.5% | ||

| Archaeological sites* | 2 198 (2013) 2 257 (2017) | 2.7% | |||

| Museums | Museums institutions and museographic collections | 973 (2013) 1.065 (2016) | 9.5% | 455 (2013) 406 (2016) | -10.8% |

| Archives | Archives | 36 (2013) ** 36 (2017) ** | 0% | ||

| Visual arts | Art galleries / exhibition halls | Na | Na | ||

| Performing arts | Scenic and stable spaces for theatre | 1 110 (2013) 1 183 (2017) | 6.6% | 374 (2013) 451 (2017) | 20.6% |

| Concert houses | 396 (2017) | 98 (2017) | |||

| Theatre companies* | 3 227 (2013) 3 966 (2017) |

22.9% | |||

| Dance and ballet companies* | 913 (2013) 833 (2017) |

-8.8% | |||

| Symphonic orchestras* | 170 (2013) 204 (2017) |

20% | |||

| Libraries | Libraries | 5 622 (2012) *** 5 450 (2016) *** | -3.1% | 849 (2012) 842 (2016) | -0.8% |

| Publishers | 314 (2015) 312 (2017) | -0.6% | 2 649 (2015) 2 721 (2017) | 2.7% | |

| Audiovisual | Cinemas* | 777 (2013) 739 (2017) | -4.9% | ||

| Recording music companies* | 60 (2013) 60 (2017) |

0% | |||

| Broadcasting organisations | Na | ||||

| Other (please explain) | |||||

Source: Ministry of Culture and Sport (several years) Cultural Statistics Yearbook.

* No distinction between public and private.

** It refers to central-owned archives (ownership of the Ministry of Culture and Sport and the Ministry of Defence)

*** Public central, regional and local libraries

Last update: February, 2019

In recent years, the outsourcing of public services has spread to the direction and management of cultural organisations. Thus, the management of both new and existing cultural services, formerly under direct governmental control, is now gradually being assigned to external companies or groups. This public management delegation of a variety of services to external organisations is part of a wider trend.

In the specific area of culture, the process began with the creation of public contractors (public culture foundations or committees, as well as specialised public companies) to accelerate management processes and provide greater flexibility in subcontracting and management of income. At the same time, many secondary services with little cultural impact were outsourced (catering, security, cleaning and even the marketing of goods or services). As a result of the limits placed on staff costs, the interest in obtaining specialised services at competitive rates, or the erosion of internal structures linking public ownership and public management, more and more services forming part of the cultural administration have been outsourced.

During the first phase of this process, publicly owned cultural organisations subcontracted secondary services with a high degree of cultural content to external providers (almost all museums and exhibition centres now have external educational and monitoring services). This was followed by the definitive transfer of all management tasks. The process now extends as far as community centres, municipal arts centres, galleries and exhibition halls, archaeological sites, concert halls, theatres and even museums.

Various national and regional institutions have also introduced changes in the procedure for appointing directors as to improve the objectivity, professionalism and transparency of candidate selection. At the central level, the pilot experience of the Prado Museum was extended to other institutions, such as the National Library of Spain, the Reina Sofia National Museum and Art Centre or the National Library of Spain.

Firstly, under the framework of the Cultural Institution Modernisation Plan, approved in September 2007, and later on, within the General Strategic Plan 2012-2015 of the State Secretariat for Culture, this process of greater autonomy in the management of the country's principal cultural institutions also sought to promote their financial sustainability through a greater public-private collaboration. The Prado Museum and the Reina Sofia National Museum and Art Centre are "special" public institutions, meaning that, under Spain's continental legal system, they can engage in transactions governed by "private law".

Sponsorship and fundraising, linked to the greater autonomy of cultural institutions, also encourages a much greater degree of co-operation with local business circles, and enables local administrators to gain experience with innovative and modern management techniques. A good example in this regard is the Barcelona Contemporary Art Museum (MACBA).

In recent years, volunteerism has spread to all sorts of cultural facilities, using formulas such as associations and foundations of Friends of Museums, which are grouped in the Spanish Federation of Friends of Museums, a non-profit established in 1983. Other examples are the Foundation of Friends of the National Library, a private and non-profit institution created in November 2009, and the Foundation of Friends of the Prado Museum with more than 21 000 members. In this line, the benefactors' programme of the Prado Museum currently provides around 30% of its internal financing.

According to the data of the Special Eurobarometer 466 on Cultural Heritage (2017), 4% of the Spanish population donates money or other resources to an organisation active in the field of cultural heritage (average EU28 was 7%), and 3% does voluntary work for heritage organisations (average EU28: 5%).

Last update: February, 2019

The promotion of Spanish culture abroad is a joint endeavour between the Ministry responsible for cultural affairs, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation. At present, the Directorate-General for Cultural Industries and Cooperation, through the Sub Directorate-General for Cultural Cooperation and Promotion Abroad, is responsible for the promotion of the Spanish cultural industries abroad.

In addition, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation is responsible for foreign cultural activities through its State Secretariat for International Development Cooperation and for Ibero-America and the Caribbean, which is part of the Spanish Agency for International Co-operation and Development (AECID). This unit also deals with cultural and scientific exchanges, including grants and scholarships, as well as Spain's international undertakings in this respect. It acts through Spanish embassies and consulates or through AECID centres on foreign soil.

The Cervantes Institute, the self-governing body set up in 1991, under the aegis of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, is entrusted with promoting the Spanish language and culture internationally, for which it has 87 centres in 44 countries.

The Spanish Public Agency for Cultural Action (AC/E) was set up in 2010 to promote and disseminate the cultural realities of Spain inside and outside the country, to joint projects of different regions and cultural institutions throughout the country and support projects that involve artists, scientists and cultural and creative industries abroad. The AC/E runs the Programme for the Internationalisation of Spanish Culture (PICE) since 2013.

Traditionally, the management of foreign cultural policy has been the subject of disputes between the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation. These ended in July 2009 when, in an attempt to reorganise functions, both Ministers agreed to establish a National Plan for Cultural Action Abroad (PACE). At present, the Culture Plan 2020 of the State Secretariat for Culture, passed in 2017, emphasizes the need for a unique strategy of cultural action abroad that reinforces the international image of Spain as cultural referent through the internationalisation of cultural and creative sectors and the promotion of cultural tourism.

In addition to the Culture Plan 2020, interministerial coordination, together with the Cervantes Institute, is embodied in the arts & culture SPAIN programme, which aims to disseminate and promote Spanish art and culture in the United States and serves as a space for dialogue and cooperation between Hispanic and American leaders.

Cultural activities abroad also rely on institutions such as:

- the Carolina Foundation, set up in 2000 to promote cultural relations (grants, research, visitor programmes), particularly with the Iberoamerican community of nations;

- the Casa de América in Madrid, set up in 1990 to promote exchange and mutual understanding between Latin American and Spanish cities);

- the Euro-Arab Foundation for Higher Studies in Granada, set up in 1995, to create a space for dialogue and cooperation between the countries of the European Union and those of the League of Arab States;

- the European Institute of the Mediterranean, set up in 1989, contributes to the promotion of Catalan and Spanish institutions in the Mediterranean area and promotes and participates in development cooperation projects;

- the Casa Asia in Barcelona, was established in 2001 with the priority objective of promoting and carrying out projects and activities that contribute towards greater mutual awareness, boosting relations between Spain and Asian and Pacific countries, particularly in institutional, economic, academic and cultural spheres. In the middle of 2007, and after its consolidation in Barcelona, Casa Asia opened a new seat in Madrid;

- the Casa África in Las Palmas, Canary Islands, set up in 2006, to provide a forum for fostering mutual understanding and strengthening links between the respective civil societies;

- the Casa Árabe and International Institute of Arab and Muslim World Studies has centres in Madrid and Córdoba and was established in 2006 with the aim of becoming an active instrument in strengthening and consolidating multifaceted relationships with Arabic and Muslim countries and establishing itself as a nucleus for the study and understanding of the history and contemporary reality of these countries;

- the Casa Sefarad-Israel, was established in 2006 to study the legacy of Sephardic culture as part of Spanish culture, foster greater knowledge of Jewish culture and promote the development of links between Spanish and Israeli societies; and

- the Casa Mediterráneo, set up in 2009 with the goal of being a centre for debate and dissemination of the numerous Mediterranean expressions.

At regional level, cultural activities carried out abroad by the autonomous governments have increased significantly over recent years. In 1992, the government of Catalonia set up the Catalan Consortium of External Promotion of Culture, today part of the Institute of Cultural Companies, to promote a Catalan presence in foreign markets. In 2007, the Etxepare Basque Institute was created with the aim of disseminating Basque culture and language abroad.

In general, those regions with significant numbers of overseas emigrants, notably Galicia, have encouraged exchanges, particularly in the area of music and dance. Communities bordering on Portugal or France often engage in cultural exchanges within the framework of European Union regional policies and programmes. Andalusia emphasises cultural cooperation with its southern neighbour, Morocco. More and more communities are using cultural diplomacy as spearheads for the promotion of trade and tourism.

From a budgetary perspective, state policy for cultural promotion abroad is mainly implemented through the budgetary programme entitled Cultural diffusion abroad. In 2017, this programme amounted to 119 447 000 EUR, which represents an increase of 0.7% on the previous year. After several years of drastic cuts in the funding of this programme, the negative trend changed in 2014 when the amount allocated to the programme (109 263 000 EUR) increased by nearly 16% compared to the previous year.

Last update: February, 2019

Spain is a member of the European Union since 1986. The Sub Directorate-General for Cultural Cooperation and Promotion Abroad of the Ministry performs the following tasks: coordination and follow-up of the actions of the Ministry related to the European Union and to other agencies and international authorities in the field of culture; participation in the elaboration of treaties, conventions and programmes of international cooperation (of bilateral or multilateral character) in those fields that affect the Ministry; and advice on Spanish participation in international organisations.

Spain participates actively in the Creative Europe (2014-2020) and Horizon 2020 Programmes. Spain is also an eligible country for the EEA-Grants in cultural and natural heritage, and diversity in culture and arts.

Regarding the Council of Europe, of which Spain has been a member since 1977, the Sub Directorate-General of International Cooperation, in conjunction with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, is also responsible for the follow-up and organisation of Spain's participation in the events that the Council of Europe sponsors, either directly or indirectly. Spain joined the Faro Convention in December 2018.

Spanish institutions participate in 22 designated Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe: The Ways of Santiago de Compostela, Vikings and Normands, The Andalusian Legacy, The Phoenicians Route, The Iron Route of the Pyrenees, The European Routes of Jew Heritage, San Martín de Tours, The Sites of Cluny Network, the Routes of the Olive Tree, the Vía Regia, Transrománica, Iter Vitis, The Cister European Route, the European Route of Cemeteries, The Route of Prehistoric Rock Art Trail, Thermal Heritage, Casa Dei, The European Route of Ceramics, Megalithic Route, Art Nouveau Network, The Routes of Charles V, and Destination Napoleon.

Spain's cultural cooperation with UNESCO, the Organisation of Education, Science and Culture, of which Spain has been a member since 1953, involves the following tasks: coordination and liaison between the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, the Spanish Embassy at UNESCO and UNESCO itself, with regard to the development of UNESCO's Conventions and Recommendations; preparation of the participation of the Ministry in the General Conference and the Inter-governmental Conferences, expert committees and other meetings at UNESCO; coordination and liaison between the National Cooperation Commission and UNESCO, and participation in, and follow-up and dissemination of, UNESCO's activities. The Ministry of Culture and Sport is currently responsible for implementing the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. On 28 April 2006, the government approved the text of the Convention and presented it to the Parliament for ratification. The instrument of ratification was deposited on 18 December 2006. On the 25th October 2006, it was approved and ratified by the King of Spain, one month later of being approved by the Senate.

In the case of the Organisation of Iberoamerican States for the Education, Science and Culture (OEI), of which Spain has been a member since 1949, the Sub Secretariat for Education, Culture and Sport, through its Sub Directorate-General for International Cooperation, coordinates the participation of the Ministry at the Iberoamerican Conferences of the Ministers of Culture, in the framework of the Iberoamerican Summits.

The MARCO programmes organised by the current Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport and the OEI currently underway, cover practically all of the cultural sectors: in the area of books, archives and libraries, ABINIA, IBERARCHIVOS-ADAI and RILVI; in the cinema and audiovisual sector, IBERMEDIA; in the field of music, IBERORQUESTAS JUVENILES, IBERMÚSICAS; in the field of the area of fine arts and cultural assets, IBERMUSEOS; in the sector of performing arts, IBERESCENA; in the area of intellectual property: FIPI; and in the area of libraries, IBERBIBLIOTECAS. Since 1982, Spain has also been a signatory to the Andrés Bello Agreement, an intergovernmental organisation that works to achieve the educational, scientific and cultural integration of Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Cuba, Chile, Ecuador, Spain, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Dominican Republic and Venezuela. Spain is also a member of the Regional Centre for Book Development in Latin America and the Caribbean (CERLALC), an intergovernmental organisation of Ibero-America, under the auspices of UNESCO, which works towards the development and integration of the region through the construction of reading societies.

Last update: February, 2019

During the last decade, probably as the result of the increasing professionalisation of the cultural sector and of the public finances crisis in Spain, Spanish cultural institutions got involved in more international cooperation networks and, in the European context, got awarded more European grants to get engaged in cooperation projects. The main funders have been Creative Europe, Horizon 2020 and Erasmus+ Programmes.

Regarding professional cooperation networks, the Sub Directorate-General for Museums of the Ministry of Culture and Sport and the Spanish Association of Cultural Heritage Managers take part in NEMO – Network of European Museum Organisations. The National Library of Spain, the Complutense University of Madrid, the University of Valencia, Dialnet, the University of Barcelona and the Basque Digital Library are members of The European Library. The Palau de la Música Catalana and the Auditorium of Barcelona are members of the network ECHO - European Concert Hall Organisations. Spanish entities and professionals are also represented in networks such as the EFA-European Festivals Association, Eurozine, RESEO, ENCATC, EBLIDA.

At the institutional level, the Reina Sofia National Museum and Art Centre, for example, is working on a new type of museum through its collaborations with networks that are not institutionalised in the conventional sense. The Network Southern Conceptualisms, comprised of a group of researchers and curators from all over Latin America, is collaborating with Reina Sofia to promote a new notion of shared heritage by generating a network of archives. The Foundation of the Commons brings together different political and cultural actors and groups and collaborates with Reina Sofia in the design of a new participative and transversal institutionality. L’Internationale proposes a new artistic, non-hierarchical and decentralized internationalism, based on the value of difference and horizontal interchange between a constellation of locally rooted and globally connected cultural agents. It is composed by six relevant European museums: Moderna galerija (MG, Ljubljana, Slovenia); Reina Sofia National Museum and Art Centre (MNCARS, Madrid, Spain); Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (MACBA, Barcelona, Spain); Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA, Antwerp, Belgium); SALT (Istanbul and Ankara, Turkey) and Van Abbemuseum (VAM, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). It also collaborates with academic institutions. Midstream is a collaborative project that seeks to analyse the role of audiences conceived not only as consumers but also as producers of content, in a context marked by the postmedia paradigm, the specificity of the production of contemporary artists and the new forms of cultural mediation. Also at the institutional level, the International Theatre Institute of the Mediterranean (IITM) aims to promote the production of performing arts, and other cultural projects, that develop and represent Mediterranean culture, fostering cultural exchange and solidarity among Mediterranean peoples involving 24 countries: 15 in Europe, 6 in Africa and 3 in the Eastern Mediterranean.