1. Cultural policy system

United Kingdom

Last update: March, 2020

The United Kingdom comprises four nations – England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, each with its own distinct culture and history. Three of these – England, Wales and Scotland – together make up Great Britain. The population of England is significantly higher than the three other nations combined. Although the following text and the chapters that follow will refer to the UK, the focus will be on England and Wales.

Although there had been ad-hoc legislation governing, for example, museums and libraries in the 19th and first 40 years of the 20th centuries and a Standing Commission on Museums and Galleries was set up in 1931 to advise government, the present UK funding system has its origins in the 1940s. The first national body to support the arts, the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) evolved in 1946 to become the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), still considered to be the first arts agency in the world to distribute government funds at "arm's length" from politicians. The Council was primarily reactive – allocating government funds for arts organisations and artists and providing help and encouragement, though for some years it was also involved in direct provision, such as touring of exhibitions. Although legally part of ACGB, Scotland and Wales had their own Arts Councils (the Arts Councilof Northern Ireland was established as an independent body in 1962). Key aims of ACGB were to develop and improve the knowledge, understanding and practice of the arts, and increase the accessibility of the arts to the public. However, a persistent dilemma over many years was the rival claims on resources of maintaining and enhancing the standards of the arts organisations it supported on the one hand and bringing the arts to as many people as possible on the other. Significantly, the various "Charters" giving the Council its mandate to operate never defined the "arts", and although the number of supported arts organisations grew, the range of artforms was still fairly narrow after 20 years. Film was not part of the Arts Council’s remit (although artists’ films were to be from the 1970s) and while the British Film Institute was established as a semi-autonomous agency in 1933, it was initially poorly funded and its focus until relatively recently was primarily on film education.

The UK Government's first Minister for the Arts, Jenny Lee, issued a government White Paper setting out a Policy for the Arts, following which the Arts Council's grant significantly increased by 45% in 1966/67 and a further 26% in 1967/68.

The Standing Commission on Museums and Galleries was given the responsibility for granting aid to national museums in 1963 and became theMuseums and Galleries Commission with its own Charter in 1987.

In the 1960s and 1970s, local authorities began to expand their support, building or refurbishing regional theatres, museums and galleries and multi-purpose civic halls, as well as running their own programmes and festivals. ACGB introduced a “Housing the Arts” fund to encourage the development of arts facilities. However, although government legislation in 1948 (updated in 1972) had given local councils legal authority to support arts and entertainment, the powers were, and remain, permissive rather than mandatory. As a consequence, support was patchy. This was also the period when regional arts associations developed in a piecemeal fashion, either as a consortium of local arts organisations, or set up by local authorities as a reaction to the closure of ACGB's regional offices.

The 1980s were a decade when political and economic pressures led to a fundamental reappraisal of the funding and management of the arts and culture in Britain. While remaining committed to the principle of public sector support, the Government required arts and culture organisations to look for new sources of revenue to supplement their income. In the years that followed, the financing of arts/culture developed from one in which the emphasis was primarily on public sector support to become largely a mixed funding model with public funds representing a diminishing proportion of the income of cultural organisations.

In 1990 the government asked the Arts Council of Great Britain to develop a National Arts and Media Strategy in partnership with the British Film Institute, Crafts Council, Scottish and Welsh Arts Councils and the regions. This was the first time that an attempt had been made to devise a co-ordinated policy to broadly guide arts funding developments. This process involved widespread consultation within the sector. However, not long after the strategy was published in late 1992, the report was, in effect, "shelved". In fact, the 1990s and the first decade of the new millennium were characterised by fundamental policy and especially structural change in arts and culture. In 1992, a re-elected Conservative Government established for the first time a co-ordinated Ministry to deal with arts, museums, libraries, heritage, media, sport and tourism called the Department of National Heritage. Then, in 1994, a fundamental decision was taken to devolve the Arts Council of Great Britain's responsibilities and functions to three new separate bodies: Arts Council of England (ACE), the Scottish Arts Council (now Creative Scotland) and the Arts Council of Wales (ACW). Each nation therefore runs its own affairs in relation to arts funding.

A significant development was the introduction of the National Lottery in the mid-1990s which brought a major new income stream for the cultural sector. Since 1994, the Lottery has raised over GB£ 40 billion for good causes supporting the arts, heritage, sport, community and voluntary groups (see chapter 7.3).

The incoming Labour administration elected in 1997 renamed the Department of National Heritage as the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (and, since 2017, known as the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport). The Government sought to reduce the number of arm's-length cultural agencies through a series of mergers on the basis of reducing bureaucracy and minimising administrative spending. The Museums & Galleries Commission and the Library & Information Commission merged to become a new body initially called Re:source and later known as the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA). The Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England was amalgamated with English Heritage.

The Arts Council of Wales went through a rather turbulent period at the end of the 1990s and early part of the new millennium, the result of several factors not least controversy over its drama strategy. Accusations were levelled at the Council suggesting it had lost the confidence of the arts community, politicians and its staff and it was subjected to several reviews. In 2006, the Minister for Culture, Welsh Language and Sports invited an independent review panel, under the chair of Elan Closs Stephens, to investigate the arts funding and management in Wales, including the role of ACW. and many of its recommendations were implemented. The report recommended how best to manage and grow national ambitions for the arts throughout Wales.

Having undergone several reorganisations itself, including its absorption of the previously separate Regional Arts Boards to become the Arts Council’s regional offices, ACE restructured yet again in 2009, with nine regional offices grouped into four geographical areas covering London, the North, the Midlands and South West and the East and South East. A key driver in the changes was the need to achieve savings, leading to an overall staff reduction of 21%.

More structural change took place following the election of a new Government in 2010, again on the basis of reducing public expenditure. ACE assumed responsibility in 2011 for museums and libraries following the abolition of the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council and the British Film Institute took over some of the functions of the UK Film Council (itself only established in 2000), following that organisation’s abolition. The National Archives Council assumed responsibility for providing strategic leadership to the archives sector and advising government on its development. In addition, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport faced significant staff reductions.

Although the new millennium brought a considerable increase in central government support for the arts in England (especially from 2000-2005) to address previous underfunding, since 2011, the cultural sector has faced considerable challenges as the result of austerity, leading to significant reductions in public funding at national and local levels. Between 2010 and 2014, Arts Council England saw its grant-in-aid from government fall by one-third. Without the Lottery, it is doubtful whether many of the (often pilot) schemes and projects would have come on stream.

In 2016 the UK Government issued a Culture White Paper, the first in more than 50 years. Among other things this restated the principle that everyone should enjoy the opportunities culture offers, but also that every publicly funded cultural organisation should increase opportunities for the most disadvantaged citizens to access culture. It also said that culture should enhance the UK’s international standing and it recognized the need for cultural investment, resilience and reform. However, with no serious evidence of a major relaxation in austerity policies and with the appointment in 2019 of yet another Secretary of State for the Culture (the eighth in nine years), it appears likely that the outlook will remain challenging for those in the cultural sector, at least in England. Moreover, there are concerns that the UK referendum decision to leave the European Union will have adverse consequences on employment opportunities, talent recruitment, European touring, and lead to further public expenditure reductions (see chapter 2.9).

Last update: March, 2020

Last update: March, 2020

The UK Parliament and Government have policy responsibility for all cultural issues in England and for some issues, such as broadcasting, across the whole of the United Kingdom. However, in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, most cultural issues are now the responsibility of the Scottish Parliament and Executive, the National Assembly for Wales, and the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive respectively ("the devolved administrations"). It should be noted that while the Scottish Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly are able to make primary legislation in respect of those issues which have been devolved, the National Assembly for Wales is only able to make secondary legislation; responsibility for primary legislation for Wales remains with the UK Parliament and Government.

Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) is responsible for government policy on the arts, sport, the National Lottery, tourism, libraries, national museums and galleries in England, broadcasting, creative industries including film, the music industry, fashion, design, advertising and the arts market, as well as digital issues, press freedom and regulation, licensing, gambling and the historic environment. DCMS also has overall responsibility for the listing of historic buildings and scheduling of ancient monuments, the export licensing of cultural goods, the management of the Government Art Collection and the Royal Parks Agency. The UK Parliament and Government retain both legislative and policy responsibility for the whole of the UK in the following areas: acceptance in lieu of tax (e.g. the acquisition of works of art and heritage for the nation instead of payment of death duties); broadcasting; export controls on cultural objects; government indemnity scheme (i.e. insurance for cultural objects on loan); legislative responsibility for the national lottery (but responsibility for policy directions is shared with the devolved administrations); public lending right (except for Northern Ireland). DCMS also retains legislative and policy responsibility for film and for alcohol and public entertainment licensing in Wales. Responsibility for gambling law and regulation is shared between the UK Parliament and the devolved administrations. All other subject areas are the responsibility of the devolved administrations.

Much of the work for which DCMS is ultimately responsible is undertaken by public bodies (Non-Departmental Public Bodies or NDPBs) which generally operate at arm’s length from government.

There is a separate Parliamentary Select Committee for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the DCMS and its associated public bodies. In recent years a number of All-Party Parliamentary Committees have been set up to look at issues in specific cultural areas, e.g. on music and on theatre. The Welsh Government also has a committee with responsibility for Culture, Welsh Language and Communication.

As this reference was being finalized rumours were circulating that DCMS could be re-organised or downsized by the new Government

Department for Education (DfE)

The DfE has overall responsibility for education and further education policy, apprenticeships and other skills in England. This includes responsibility for the national curriculum for art and design and guidance for music hubs to ensure pupils have access to music education (see chapter 5.2.). It works closely with local authorities who are the providers of state education at local level.

Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

The Department was established following the merger of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and the Department for Energy and Climate Change. It has established sector-based deals including with the creative industries sector (see chapter 3.5.1.).

Department for International Trade (DIT)

The DIT promotes British trade and investment globally, which is even more important in the context of Brexit. Any trade missions involving culture would be co-ordinated by the DIT. It also part funds the British Film Commission through UK Trade and Investment

Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO)

In its role as the chief instrument for foreign affairs, the FCO sponsors the British Council, an executive NDPB responsible for promoting cultural and educational programmes to build cultural relations with the peoples of other countries (see chapter 1.4.1.). The BBC World Service is a public corporation of the FCO that promotes new reports and analyses in English and 27 other languages. The FCO oversees the Chevening Scholarship Programme, which awards scholarships to support overseas students to study at UK universities.

Ministry of Defence (MOD)

The MOD has relationships with six military museums, some of which are classified as executive Non-Departmental Public Bodies (NDPBs) sponsored by the Ministry.

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG)

The MHCLG is the ministry responsible for relationships with local authorities. It also has responsibility for architecture including the Architects Registration Board, which regulates the architects’ profession.

Arts Council England

Arts Council England (ACE) is the national agency responsible for supporting the arts, museums and libraries in England with government and National Lottery funds. It was established in 1994 to replace the Arts Council of Great Britain. It operates under a Royal Charter (as amended in 2008 and 2011) with a mission to: develop and improve the knowledge, understanding and practice of the arts; increase accessibility of the arts; advance the education and further the establishment, maintenance and operation of museums and libraries. It is also obliged to advise and co-operate with government, local authorities and others.

Historically, the UK system of support for culture has been regarded as the archetypal "arm’s length" model, with successive governments choosing the Arts Council and other NDPBs as the instruments which administer the disbursement of government funds for culture and determine who the beneficiaries will be. Arguably, the arm's length principle is essentially a "convention" between government and the various cultural agencies, and the terms of these relationships are set down in management standards agreed with DCMS. Certainly, the nature of the relationship between central government and ACE has been tested over the years, with Government being seen as more interventionist on issues such as indicating broad policy directions or requiring cost savings and the structural reform of the Council and other NDPBs.

ACE provides financial support in the areas of music, drama, dance, literature, visual arts, photography, crafts, carnival, circus and digital. Despite its name, ACE also supports museums (except national museums funded directly by DCMS) and libraries as a result of the closing by the government of the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council in 2011. In relation to museums, ACE provides standards, funding and advocacy. The period from 1990 until 2013 was a period of frequent structural change in the arts and museums sectors, usually because of the need to reduce administrative costs prompted by government. In the early 2000s, for example, the Arts Council and separate regional arts boards were merged into a single organisation.

In 2012 a Review of the Governance of Arts Council England by David Norgrove led to further changes, in this case a 50% reduction in administration costs as a result of the planned cuts to the Council’s grant from government of 29.6% over the period 2012-2015 and the acquisition of responsibility for the museums and libraries. This resulted in further staff reductions.

ACE’s 10-year strategic framework from 2010 (revised in 2013 as Great Arts and Culture for Everyone) identified five goals for arts, museums and libraries to ensure: excellence is thriving and celebrated; everyone has the opportunity to experience and be inspired by them; they are resilient and environmentally sustainable; their leadership and workforce is diverse and skilled; and every child/young person has the opportunity to experience them. In 2018/19 68% of ACE’s income came from government grant-in-aid (mostly fromDCMS, but also some from DfE in respect of music and cultural education) and 31% came from the National Lottery. The majority of ACE’s support for 2018-2022 will go to 829 National Portfolio Organisations (NPOs), who will receive a total of GB£ 338 million annually plus a further GB£ 71.3 million from the National Lottery for touring and work with children and young people. The funding agreements with the NPOs have been extended from three years to four. In addition, Arts Council National Lottery Project Grants support thousands of artists, community and cultural organisations and has a budget for 2019/20 of GB£ 97.2 million.

British Film Institute

The British Film Institute is the lead organisation for film in the UK. It is responsible for the National Film Archive and Reuben Library (which has the largest collection of material about film, TV and the moving image in the world) and runs the National Film Theatre, BFI IMAX Cinema and London Film Festival. It took over a number of responsibilities of the UK Film Council when the latter was abolished and now awards National Lottery Funding to support film production, distribution, education, audience development, market intelligence and research. BFI2022 is the Institute’s five-year strategic plan that builds on its previous strategy, Film Forever, and follows UK-wide consultation. It focusses on the development of future talent, education and skills and audiences (see chapter 3.5.3).

Crafts Council

The Crafts Council was established in 1971 as the Crafts Advisory Committee to advise government on the needs of artist-craftsmen and to promote nationwide interest and improvement in their products. Subsequently, it was renamed the Crafts Council and was granted a Royal Charter in 1982 to advance and encourage the creation and conservation of works of fine craftsmanship and to promote public interest in the work of craftsmen (see 3.4). It is now funded by ACE.

Other agencies

DCMS supports and works with a number of other agencies (some of which are referred to elsewhere, especially in chapter 3). Briefly, these are:

Royal Parks an executive agency responsible for managing and preserving over 5,000 acres of historic parkland across London.

BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) is a public corporation whose main responsibility is to provide impartial public service broadcasting.

Channel 4 is also a public service broadcaster and public corporation, that works across television, film and digital media.

Historic Royal Palaces is a public corporation that manages Britain’s unoccupied royal palaces.

Advisory non-departmental public bodies

The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest advises the government on the export of cultural property.

The Theatres Trust is the national advisory body for theatre, promoting the value and maintenance of theatre buildings.

The Treasure Valuation Committee comprises independent experts to establish the likely market value of each treasure find.

Executive non-departmental public bodies

The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) is the world’s largest museum of decorative art and design. Based in London it has a new museum in Dundee.

The Science Museum Group is devoted to the history and contemporary practice of science, medicine, technology, industry and media, and consists of: the Science Museum, Museum of Science and Industry, National Railway Museum (York), National Media Museum and National Railway Museum (Shildon).

The Tate holds the national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art and has a network of four museums: Tate Britain (London), Tate Liverpool, Tate St Ives and Tate Modern (London).

The Royal Museums Greenwich comprises the National Maritime Museum, the Royal Observatory and the Queen’s House.

The Natural History Museum comprises some seven million items.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund uses money raised by the National Lottery to help people across the UK to explore, enjoy and protect the heritage.

Historic Englandis the government’s statutory advisor on the historic environment.

Visit England and Visit Britain are respectively the National Tourist Board for England, which plans national tourism strategy, and the national tourism agency responsible for marketing Britain worldwide and developing Britain’s visitor economy.

UK Sport (UKSP) and Sport England (SE): UKSP supports Britain’s Olympic and Paralympic sports and athletes, co-ordinating bids for and staging of major international sporting events in the UK, while SE encourages people to take up sport and also protects existing sports provision.

The British Library has one of the world’s biggest library collections.

The British Museum was the first national public museum in the world and its permanent collection is amongst the largest and most comprehensive in existence.

The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) is part of UK Research and Innovation, a NDPB funded by government, and funds independent research in a wide range of sectors including the creative and performing arts, design, digital content and heritage.

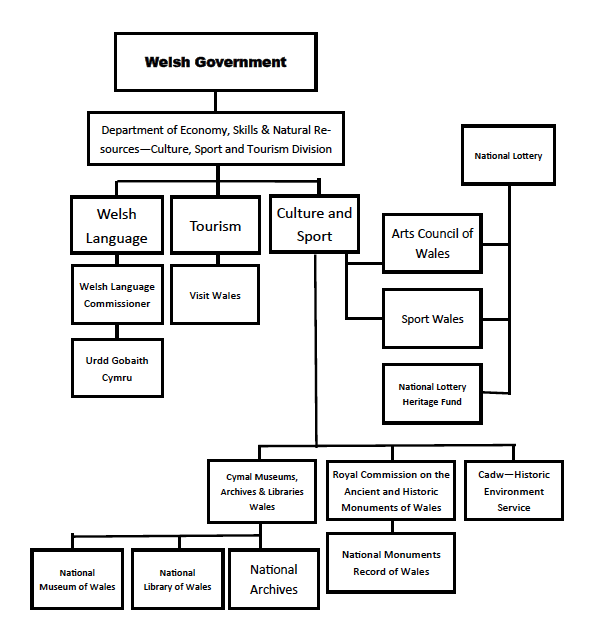

WALES

The National Assembly for Wales has devolved responsibilities in Wales for culture and related issues. Since 1999 a number of public agencies, e.g. the Arts Council of Wales and Sports Council for Wales have been funded by, and accountable to, the Assembly. Within the Welsh Government cultural policy is a particular focus of the Deputy Minister for Culture, Sport and Tourism and the Minister for International Relations and the Welsh Language. Other ministers will also have an interest, e.g. the Minister for Educatio. The principal agency for arts support is the Arts Council of Wales (ACW). While respecting the independence of the ACW when it comes to decisions concerning how the arts are funded, in common with other Welsh Government Sponsored Bodies ACW is expected to reflect the Government’s priorities and its aims. Arguably, the relationship between ACW and the Welsh Government is a little closer than that of ACE to the UK Government. Compared to the experience in England, reductions in government funding for culture in Wales have been less severe. ACWwas established by Royal Charter in 1994 to support and develop the arts in Wales. This followed almost 50 years as the Welsh Arts Council, which was legally part of the Arts Council of Great Britain though mostly operationally independent from it. Priorities in ACW’s Corporate Plan for 2018-2023 are: developing the capability and potential of those working in the arts in Wales; building diversity, equality and inclusion through encouraging a greater number and wider range of people to enjoy and participate in the arts; and supporting a dynamic and resilient arts sector. The Council also has a role in ensuring the arts contribute to priorities of the Welsh Government agenda, including stimulating jobs and skills, assisting with the implementation of the Government’s Culture and Poverty Report and helping to fulfil the seven goals of the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 that seeks to improve the social, environment and cultural wellbeing of Wales in accordance with sustainable development. Indeed, ACW has a statutory duty to embed sustainable development into its organisation (see also chapter 2.7). ACW’s grant-in-aid from the Welsh Government is GB£ 31.7 million in 2019/20, much of which is allocated to 67 revenue-funded organisations that comprise its Arts Portfolio.

The Welsh Assembly Government's historic environment division (CADW: Welsh Historic Monuments) is responsible for the built heritage. The Design Commission for Wales promotes sustainable development by providing bespoke training to councillors, planners etc., championing best practice and acting as a non-statutory consultee within the urban planning process. CyMAL: Museums, Archives and Libraries Wales was established as a policy division of the Welsh Government from April 2004 to develop strategic direction for local museums, archives and libraries and provide financial support and advice. In 2007, CyMAL took over the sponsorship role for the National Museum Wales and the National Library of Wales.

Last update: March, 2020

There are no regional government authorities in England and Wales, but some central government functions have been transferred to a small number of metropolitan areas (e.g. London, Greater Manchester and the West Midland) In the past there have been regional groupings to advise and deliver policies and/or funds in specific areas, e.g. Regional Arts Associations (Boards) or regional constructs such as the Regional Cultural Consortia that were established in England in the first decade of the millennium and worked with the Regional Development Agencies and Regional Government Offices that were operational at that time.

Last update: March, 2020

Local authorities are important players in the provision and funding of cultural services. The Museums Act 1849 enabled local authorities to spend money on museum provision and the Libraries Act the following year gave them a statutory responsibility to make provision for libraries. However, support for the arts was primarily a post-World War II development. The Local Government Act 1948 empowered local authorities in England and Wales to spend up to a 6d (2 1/2p) rate on entertainment and the arts. Although the upper limit was removed by the Local Government Act 1972 very few local authorities got anywhere near spending the maximum amount permitted under the previous legislation. Nevertheless, some local authorities, especially cities and urban areas, took the permissive powers seriously as they were increasingly encouraged to become partners in arts provision with the Arts Councils and by the Government White Paper, A Policy for the Arts (1965).

However, for several years local authorities have been under considerable pressure because of governmental austerity policies – in the period 2010-2016 they experienced a 40% reduction in their grant from central government. This has had a detrimental impact on the cultural budgets and programmes of many local authorities, especially as arts and museum provision is not a statutory obligation. However, even library provision, which is a legal responsibility, has not been immune from the effects with many libraries closed and/or opening hours reduced as some local councils seek to provide a minimal level of service while still complying with legislation (see 3.2). Estimates suggest that local authority spending on culture had fallen by GB£ 390 million between 2011 – 2019 according to an analysis by the County Councils Network. Over one-third of 375 local authorities in England and Wales no longer have a dedicated arts officer or service. Some local councils have contracted out arts provision to private companies or voluntary organisations or enlisted voluntary workers because of the loss of trained or specialist staff.

Attempts have been made in recent years to stimulate local authority provision, e.g. in the introduction of competitive accolades such as the UK City of Culture and London’s Borough of Culture (see chapter 2.7). The success and legacy of Liverpool, European Capital of Culture 2007 has also been a factor in encouraging some local authorities not to seriously reduce their commitment to cultural activity.

Last update: March, 2020

NGOs such as advocacy groups, foundations and charitable organisations, research institutions, representative bodies and trade unions have an important role in England and Wales contributing to policy debate, providing resources for research or inquiries to advance the cultural agenda or campaigning on behalf of specific interest groups or arts as a whole. Here are some of the more prominent:

The National Campaign for the Arts is an advocate for more public funding, investment and recognition of the arts. It also hosts an annual Hearts for the Arts Award in partnership with others to honour local authorities and individual councillors or officers who have overcome financial challenges to ensure the arts remain at the centre of community life. It produced the Arts Index 2007-2016 with indicators of trends in such things as audience sizes.

The Creative Industries Federation is an independent membership body that undertakes research, advocacy and policy work to support the UK Creative Industries (see chapter 3.5.1.).

NESTA was established with National Lottery funds in the late 1990s as the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts, focussing on a range of areas including the arts and creative economy, the Arts Impact Fund and, by 2021, it is expected to become the world’s leading centre of quantitative research on the creative economy (see also chapters 2.6, 2.8 and 3.5.1).

The Museums Association, established in 1889, is the oldest museums association in the world with more than 500 museums and 10,000 individuals in membership. It campaigns on behalf of museum sector interests. In 2008 in conjunction with the Local Government Association it issued guidelines for museums on the sensitive issue of the disposal of items in their collections.

The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (UK Branch) has been notable for its contribution to enriching the arts debate by commissioning ground-breaking research or inquiries especially in the 1970s and 1980s, e.g. on ethnic minority arts (The Arts Britain Ignores by Naseem Khan) in 1976 and Support for the Arts in England and Wales by Lord Redcliffe Maude the same year. The focus of its 2014-2019 strategy includes arts with a social impact and it has been conducting a national inquiry into A Civic Role for Arts Organisations (see also chapter 2.7.).

The Esmée Fairbairn Foundation is one of the largest independent grant-makers in the UK. It aims to improve the quality of life of people and communities and in 2018 awarded grants of GB£ 40.5 million to a wide range of work within the arts, children and young people, and social change areas.

The Paul Hamlyn Foundation is an independent grant-making organisation which seeks to help people overcome adversity, and the Clore Duffield Foundation supports cultural learning.

a-n (The Artists Information Company) works through information and advocacy to stimulate and support contemporary arts practice and affirm the value of artists in society.

Trade Unions such as the Musicians’ Union, British Actors Equity and BECTU (Broadcasting, Entertainment, Cinematography and Theatre) campaign on behalf of their members’ interests or for the interests of the arts as a whole. British Actors Equity for example has been lobbying Arts Council England to take a greater stand against projects it funds paying low wages in contravention of the condition of the grants and has a campaign, Safe Spaces, to counteract unacceptable behaviour.

Sector-specific societies who collect and/or distribute copyright royalties to their members (see chapter 4.1.6.) may also lobby government about issues that affect the intellectual rights interests of their members.

Last update: March, 2020

The Government of New Labour (1997-2010) was committed to ensuring greater coordination between government departments and between tiers of governance to ensure effective delivery of policy. This related both to cultural matters and to cross-cutting issues such as social exclusion (e.g. areas of poverty and deprivation, disaffected young people, ethnic minority groups). Thus, there was the emergence of a more integrated system (in England at least), which enabled central government policy priorities to be pursued more directly at local and regional level. However, this unravelled following the abolition of the Regional Cultural Consortia that were set up in England to develop integrated cultural strategies and ensure that culture has a strong voice in regional development, and the decision by the New Coalition Government elected in 2010 to abolish the Regional Development Agencies and the Regional Government Offices.

Nevertheless, in recent years there appears to have been greater recognition of the necessity for more collaboration between Government departments, local authorities, sector-specific bodies, cultural agencies and the need to develop cross-governmental strategies involving health, education, communities, crime prevention, etc. This is being driven by different factors such as greater acknowledgement by the Arts Councils of potential fruitful linkages between culture and other areas and an appreciation that partnerships with arts/cultural ‘actors’ can extend the impact of cultural projects. The importance of ‘joined-up’ approaches is also increasingly recognized by politicians, not least because of the considerable pressure on public funds in areas such as health, education and local communities. This has been especially evident in relation to wellbeing, e.g. the All-Parliamentary Group report Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing of 2017 recommended that the Secretaries of State of DCMS, Health, Education and Communities & Local Government should develop a cross-governmental strategy to support the delivery of health and wellbeing through arts and culture (see chapter 2.7.). The following year a cross-governmental strategy on loneliness was launched that factors in social prescribing by the medical profession of arts and culture to address the issue and the DCMS brief is to include tackling the problem through its areas of responsibility (see chapter 2.7.)

A programme to establish systematic engagement between creative organisations and academics has been piloted. Building on an initiative developed in London, the Cultural Capital Exchange has led a pilot programme to establish a national network of partnerships between creative organisations and higher education institutions to share best practice and lessons learnt from projects.

Arts Council Wales has a partnership with the broadcaster BBC Cymru Wales and the Welsh language TV channel S4C, which has enabled new opportunities to develop and promote creative talent. One initiative, Horizons-Gerwelion, jointly funded by ACW and BBC Cymru Wales, sought to grow new musical talent by providing a platform for contemporary music at live broadcast events across Wales in 2014/15.

Collaborative research between the Arts Councils in England and Republic of Ireland, Creative England, the European Centre for Creative Economy in Nordrhein-Westfalen in Germany, the European Cultural Foundation and the European Creative Business Network in the Netherlands examined the ‘spill over’ effects of culture and the creative industries. The focus of the study was an analysis of surveys, case studies and literature from 17 European countries that revealed the broader impact cultural projects subsequently had on places, society and the economy. By also reviewing the methodologies employed in the impact studies, the analysis, by Tom Fleming Creative Consultants, sought to produce an evidence base with guidance for future research.

The project Living Places involved ACE, the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, English Heritage and Sport England. Working with local authorities and developers, it aims to ensure all communities, particularly those facing housing-led growth and regeneration, have access to good quality cultural and sporting opportunities as a fundamental part of community provision (see chapter 2.7.).

Last update: March, 2020

Although there is engagement between the public and private sectors is some areas of culture, there has also been a tendency for the two worlds to develop separately. Theatre is one area where the private/commercial theatre has benefitted from interaction with the public sphere.

For many years London's commercial (West End) theatres have often relied for their programming on productions of new plays first presented in public subsidised theatres. The obvious reason for this symbiotic relationship is a financial one: hitherto, public funding has enabled subsidised companies to be more adventurous in their programmes. Indeed, it is usually one of the requirements for grant-in-aid that companies demonstrate their willingness to present new work, be more experimental, take risks etc. In turn, the subsidised theatre companies (or at least some directors and playwrights etc) have benefited from the commercial transfer and exploitation of their work. There is also a tradition of actors and other performers moving between the subsidised sector, commercial theatre and broadcasting. The importance of the public sector to the commercial theatre is explored in a 2015 report on The Interdependence of Public and Private Finance in British Theatre (see chapter 3.3)

Last update: March, 2020

Table 1: Cultural institutions, by sector and domain

| Domain | Cultural institutions (subdomains) | Public sector | Private sector | Public and private sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage sites (recognised) | 400+ England[1] 130+ Wales[2] | ||

| Archaeological sites | 190+ UK[3] | |||

| Museums | Museum institutions | 2,500 UK[4] | ||

| Archives | Archive institutions | 2140 England[5] 83 Wales[6] | 172 England[7] 10 Wales[8] | |

| Visual arts | Public art galleries / exhibition halls | Included in museums above[9] | ||

| Performing arts | Scenic and stable spaces for theatre | 1,300 active UK[10] | ||

| Concert houses | 59 England[11] 5 Wales[12] | |||

| Theatre companies | 985 England[13] 224 Wales[14] | |||

| Dance and ballet companies | 12 England[15] 1 Wales[16] | |||

| Symphonic orchestras | ||||

| Libraries | Libraries | 4,145 UK[17] | ||

| Audiovisual | Cinemas: sites | 632 England[18] 50 Wales[19] | ||

| Cinemas: screens | 3,457 England[20] 207 Wales[21] | |||

| Broadcasting organisations | 5 multichannel TV + S4C UK[22] 40 BBC local radio stations[23] | 12 main multichannel TV + specialist & single channel UK[24] Over 250 independent local radio stations[25] | ||

| Interdisciplinary | Socio-cultural centres / cultural houses | n/a | n/a | n/a |

[1] English Heritage 2019

[2] CADW 2019

[3] ARCHIUK database (www.archiuk.com) undated

[4] Museums Association 2017

[5] Refers to national, specialist, local and university archives (National Archives – undated)

[6] ibid.

[7] Refers to private and business archives (National Archives – undated)

[8] ibid.

[9] Included in ‘museum institutions’

[10] Estimated figure (Theatres Trust, undated, www.theatrestrust.org.uk)

[11] Primarily public and includes recital halls and studio halls, excludes multi-purpose venues where orchestral concerts and music recitals are only occasional (Wikipedia)

[12] ibid.

[13] Refers to companies with more than one employee, ACE, Analysis of Theatre in England, 2016

[14] Refers to production companies and includes opera and dance (www.theatre-wales.co.uk)

[15] Dance Online (https://www.danceonline.co.uk/)

[16] ibid.

[17] Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) Annual Survey of British Libraries 2013/14. (NB: This figure has been reduced since due to cutbacks in local authorities’ expenditure.)

[18] BFI Statistical Yearbook 2018

[19] ibid.

[20] ibid.

[21] ibid.

[22] Various sources. 2018-19 (NB There are hundreds of TV channels in the UK. It is difficult to provide an accurate figure because some services are duplicated, or high definition versions, or time-shifted option.) The 5 multichannel Public Service Broadcasters (especially BBC and ITV) operate many channels, including regional ones, S4C or the Welsh Language Channel.

[23] BBC

[24] Various sources 2018-19 (NB There are 12 main private channels, e.g. Sky, A&E Networks, etc) operating multiple channels. In addition, there are specialist and single channels covering music, shopping, sport, etc.)

[25] These are often owned by large commercial groups (www.radioandtelly.co.uk)

Last update: March, 2020

A comment on the Arts Portfolio Waleswebsite that “It’s tough out there, particularly for arts organisations” reflects the reality not only in Wales, but also in England. Indeed, cultural organisations in the public sphere as a whole are facing considerable challenges in the context of diminishing public funds at both central and local levels, especially in England, and generally less available sponsorship and support from business.

At the same time, the obligations of cultural organisations to their paymasters for the monies they receive has increased noticeably. In recent years cultural organisations have been required to diversify funding streams, deliver high quality and innovative work and demonstrate its relevance, widen engagement with (and broaden the diversity of) their audiences, engage young people, ensure good governance and effective business planning, provide fair remuneration for creative professionals, ensure their staff and boards are more representative of the population as a whole, build bridges with their local communities, develop international connections if relevant, provide value for money, and more.

These are all absolutely justifiable goals, but it would seem that some organisations are finding the increased number of demands made on them is becoming difficult to deal with. A credible defence of the funding agencies is that in dispensing relatively large sums of government money they have a duty to ensure the organisations they support understand and endeavour to comply with their targets. For cultural organisations even the status of being a National Portfolio organisation, with the promise of multi-year funding that accompanies it, is no guarantee of financial security. A number of NPOs are considered to be at risk of not meeting their financial goals or failing to meet their obligations in other ways. Furthermore, multi-annual funding agreements between Arts Councils and their NPOs are dependent on sufficient funding being provided by governments.

Last update: March, 2020

Responsibility for promoting UK ‘soft power’, both directly and indirectly, is shared between several government departments and arm’s-length agencies. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) is the government department that has oversight of cultural relations/diplomacy with other countries, but the main instrument for delivering cultural and educational engagement internationally is the British Council. The FCO provides some financial support to the British Council and gives overall policy guidance to it – while respecting the Council’s independent status. For instance, the FCO might enlist the Council’s assistance to promote cultural relations activities in countries or regions where UK foreign relations are problematic. The BBC World Service is a public corporation of the FCO and until 2014 was financed by it. However, as part of government cuts, financial responsibility was transferred to the BBC itself, but without resources, which led to further reductions in BBC World Service Output.

In the past decade or so, the British Government has entered into formal agreements/memoranda of cultural understanding with several other countries to promote cultural co-operation, including Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, South Korea and Saudi Arabia. These are overseen by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and the cultural programmes administered by the British Council. Bilateral seasons of culture are organized by the British Council in consultation with DCMS and the FCO. Examples include the UK-China Year of Cultural Exchange 2015, India, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates in 2017 and Germany in 2018. DCMS and the British Council manage a GB£ 30 million Cultural Protection Fund from 2016 to 2020 to support social and economic development through capacity building and safeguarding the cultural heritage in areas of risk overseas.

The previous Department of Trade and Industry supported trade missions involving the creative and cultural sector and it is anticipated its successor, the Department for International Trade, will continue this especially in the context of Brexit. Indeed, post-Brexit there is expectation that there could be more engagement with China given the phenomenal expansion of the museums and cultural infrastructure in that country.

The Department for International Development (DFID) manages Britain’s aid to developing countries and works to eliminate extreme poverty. It has supported a small number of development projects that involve culture.

As the main instrument promoting the UK’s cultural and educational relations, the British Council states that its purpose is to “build engagement and trust for the UK through the exchange of knowledge and ideas between people worldwide”. It was established in 1934 and now has offices in more than 100 countries. More than two-thirds of the Council’s income is generated from teaching English, administering examinations overseas and from other contracts and partnerships. The remainder is provided by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

The Council’s Arts Strategy 2016-21 seeks to strengthen international connections, positioning the UK as a global hub for collaboration, capacity building and policy development. Thus it focuses on fostering co-operation and networking, creating new opportunities for artists and organisations to work internationally and introducing UK creativity to global audiences. It also seeks to strengthen the arts sector worldwide by developing the capacity to innovate, reach new audiences and develop new skills, and to create safe spaces for culture, creative exploration and exchange as instruments for social change. Establishing trust is integral to the Council’s work and it considers cultural projects can have an important role in peace-building by providing a more neutral ground for developing mutual understanding. This was emphasized in a report, The Art of Peace that it issued in 2019 on the basis of an evidence review and case studies by the University of West Scotland.

Among British Council initiatives is an awards scheme for International Young and Creative Entrepreneurs. The objective has been to support and sustain the next generation of international leaders in the creative/cultural sector from emerging economies, enabling them to visit and network with UK creative entrepreneurs.

The British Council has been collaborating with the Goethe-Institut in a joint research initiative, the Cultural Value Project, which seeks to build a better understanding of the impact and value of cultural relations, especially with regard to supporting stability and prosperity in societies undergoing substantial change. A literature review (Cultural Value: Cultural Relations in Societies in Transition) was produced in 2018 in conjunction with the Herte School of Government (Berlin) and the Open University (Milton Keynes).

In 2017-18 the British Council’s income was approaching GB£ 1.2 billion (almost 9% higher than the previous year). Government funding from the FCO represented GB£ 168million (c. 14%). The majority of the Council’s income came from exams, teaching and contracts, continuing the upward trend of generating more funds through its work.

From 2015-2018Arts Council England was investing GB£ 18 million to encourage artists and cultural organisations to develop their work, promote collaboration and grow networks internationally. As part of this, ACE’s International Showcasing Fund has invested in projects that introduced English culture to international promoters and is to offer up to GB£ 750,000 to an organisation or consortium to deliver a showcase event focussing on theatre, dance and circus at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe from 2021. Arts Council Wales already has a showcase at the event. ACE’s Strategic Touring Programme 2015-2017 funded a significant number of projects to tour international work in England. ACE has signed a memorandum of understanding with the National Arts Council Singapore and also with Arts Council Korea. A GB£ 1.4 million collaboration between ACE and Arts Council Korea is supporting 21 projects in the two countries. Re:imagine India is a GB£ 1.8 million cultural exchange programme with the South Asian country and represents another collaboration between ACE and the British Council.

At Welsh Government level, international cultural engagement is of interest to the Minister for International Relations and Welsh Language and the Deputy Minister for Culture, Sport and Tourism. The International Strategy 2019-2024 for Arts Council Wales (ACW), Wales Arts: A Bridge to the World, has five key aims: giving Welsh culture a larger international platform; working closely with the Welsh Government on its international objectives; redefining its relationship with Europe; building cultural bridges with international communities in Wales; and providing more information for audiences. The strategy was developed by Wales Arts International (WAI), an in-house agency of the Arts Council which is also supported by British Council Wales. ACW is obliged to inform the new Welsh Assembly Government Strategy for International Engagement, in particular on ways in which the arts sector can assist the promotion of Wales and exploit economic opportunities overseas.

It has also been required by Government to contribute to the UNESCO Year of Indigenous Languages. The International focus of ACW and WAI reflect the country priorities of the Welsh Government: Canada, India, Ireland and China. A China-Wales Memorandum of Cultural Understanding has stimulated greater engagement between the two countries, including a government-led export market visit to China and Hong Kong that encouraged the participation of Welsh creative industries and cultural sectors. Japan is also a featured country for WAI and Welsh cultural events were organized there to coincide with the 2019 Rugby World Cup.

In 2018 a report commissioned byBritish Council Wales found that the country’s cultural offer needed to be clearer and bolder internationally and there was a need for a more integrated and strategic approach in policy, funding, practice and delivery.

Visiting Arts has sought to strengthen intercultural dialogue through international artistical creative agreements, focusing on information, training and professional development. It has had to seek new resources following the loss of its portfolio grant from ACE and is merging with Farnham Maltings, a cultural organisation offering arts and film programmes and hosting resident theatre and dance companies producing and touring work nationally and internationally. Some VA initiatives such as the Cultural Attache Network are expected to continue.

Several organisations in the UK run international cultural education and training programmes. The British Council offers a number of scholarships to overseas students to study in the UK. It is also involved with youth exchange, teaching exchange, schools partnerships and training/work experience abroad. The Clore Leadership Programme (an initiative that aims to help to train and develop a new generation of leaders for the cultural sector in the UK) can also include opportunities for international training/experience.

The UK offers an insurance guarantee for cultural objects on loan for exhibitions called the Government Indemnity Scheme (see chapter 3.1).

In its five-year strategic plan, BFI 2022, the British Film Institute is committed to increase its International Fund and strengthen its international strategy in partnership with the British Film Commission and the Department for International Trade. It will continue to champion UK film skills and talent internationally, seek to boost co-production and work with international sales agents to help promote British film at festivals and markets internationally. The UK currently has active bi-lateral film co-production treaties: with Australia, Brazil, Canada, China and China TV, France, India, Israel, Jamaica, Morocco, New Zealand, Occupied Palestinian Territories as well as South Africa and South Africa TV.

In 2014 the House of Lords Select Committee on Soft Power and the UK’s Influence produced the report Persuasion and Power in the Modern World. This recommended government action including the need for a “long-term strategic narrative about the international role of the UK”. The scope covered issues such as co-ordination, resources, cultural assets, education and science, exports, smart power and international aid programmes. Although the attention of the Lords was timely, there were some paradoxes in its approach and conclusions implicit in the report’s title. For instance, the emphasis on a rather old-fashioned one-sided diplomacy based on what advantages could be gained by the UK rather than the contemporary approach of the British Council based on mutuality. The case for greater action on soft power was also made in a British Academy report the same year, The Art of Attraction: Soft Power and the UK’s Role in the World. This considered that the government failed to recognise the value of UK soft power assets such as arts and museums, education and the BBC World Service, all of which had been subject to financial cutbacks.

More recently, the British Council issued a report, Soft Power Superpowers, that explored major trends in soft power today and the global expansion of cultural institutes from China, South Korea and Russia. It assessed the status of the UK as a major soft power player and said this was being undermined due to financial pressure on the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, which has affected the work of the BBC World Service and the British Council and noted how UK visa regulations could act as a barrier to international engagement (see also chapter 1.4.3).

Last update: March, 2020

UK Representation to the European Union is a responsibility of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). The UK is a founding member of the Council of Europe and the UK Delegation to the Council is also part of the FCO. The UK Government, through theDepartment for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and in consultation with the devolved administrations, has had the lead responsibility for cultural cooperation in the EU, and on cultural policy issues in the Council of Europe.

The UK Government had been one of the founders of UNESCO and after a 12-year absence due to financial and political differences, the UK re-joined in 1997. It adheres to many UNESCO Conventions, but although it signed the 1934 Hague Convention that requires signatories to protect cultural property during military conflict, a decision to ratify it was not made until 2015, no doubt prompted by the destruction and looting of the heritage in Iraq and Syria.

The DCMS is the government department responsible for the implementation of the UNESCO Convention of the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions and also the implementation of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention. A number of UK cities have been designated UNESCO creative cities – Bradford, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Norwich and York – and so are among those represented in the Creatives Cities Network as recognising culture and creativity as a strategic driver for sustainable urban development.

The British Council and the British Film Institute lead the Creative Europe Desk UK, which supports organisations to access funds from the EU’s Creative Europe programme. According to the Creative Europe Desk UK, grants from the programme are worth an average of €18.4 million a year to the UK cultural and audiovisual sectors. From 2014-2017 the UK benefitted by €74 million through the MEDIA sub-programme and 150 organisations received €18.7 million to participate in the Culture sub-programmes through 142 projects. The Impact of Creative Europe in the UK by Drew Wylie Projects is an analysis for the Creative Europe Desk UK (for other reports on the impact of EU funds for UK culture, see chapter 2.9). The UK is one of the most partnered of EU countries in the Creative Europe programme and there is concern that Brexit will impact the capacity of the creative and cultural sector to access finance, audiences and markets in Europe and undermine the ability to form partnerships and networks. At the time this text was being prepared, it was expected that UK organisations would be able to participate in EU programme funding and continue to apply to calls for applications during a transition period until December 2020. In the case of a no-deal scenario, the UK Government indicated it will underwrite the payments of awards to UK organisations for the duration of the project.

English and Welsh heritage bodies participate in international groups, e.g. the International Committee on the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage and the International Council on Monuments and Sites; and support European Heritage Days, an initiative of the Council of Europe and the UK and Welsh Governments, Natural England and Countryside Council have been joint organisers of the UK Landscape Award. The winner of the Award represents the UK in the Council of Europe Landscape Award.

Both Arts Council England and the Arts Council of Wales are members of the International Federation of Arts Councils and Cultural Agencies (IFACCA).

Last update: March, 2020

Many UK cultural organisations and practitioners engage in international work, such as sector specific networking, artists residencies, cooperation between major museums or opera houses and their counterparts in other countries, or projects involving small scale theatre or dance companies. It is an integral dimension of the work of many cultural organisations and individuals.

In a survey of 1,000 stakeholders conducted by ICM and SQW for Arts Council Englandin 2017, more than 50% said cultural exchange was very important to their work and two-thirds had undertaken at least one international activity in the previous two years. According to theIncorporated Society of Musicians, 70% of UK-based professional musicians travel overseas to work, while a-n (Artists Newsletter) indicated that 40% of usual artists from the UK travelled regularly to Europe in the 12 months to July 2017. The extent of international engagement was further illustrated in an Arts Council England survey of its National Portfolio Organisations (NPOs), which revealed that almost two-thirds of them had participated in international activities, most often touring, co-production or taking artists overseas. Moreover, on average international activity represented 14% of participating NPO’s income.

The British Council is involved in a number of partnerships, including one with IETM (International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts) and others in a project, Europe Beyond Disability, which seeks to explore and celebrate the innovative artistic practice of artists with disabilities (see also chapter 2.5.6). It also led a project to establish a European Creative Hubs Network in partnership with six creative hubs co-funded by the Creative Europe programme.

England and Wales host a range of well-established international cultural events, as well as many festivals and activities programmed by national and local authorities, organisations and venues, for example the Notting Hill Carnival (Europe's largest street event) was established in 1964. The Frieze Art Fair has been building a major international reputation among artists, galleries and art dealers and in Wales the Hay Literary Festival and the ARTES MUNDI contemporary art competition are important international events. A UK City of Culture programme has been instituted to take place every four years (see chapter 2.7).

Visa rules

During the past decade there has been greater awareness by the Arts Councils in England and Wales of the relevance of international cultural engagement and the need to encourage this, not least financially. However, finding sufficient resources to undertake the work can still prove challenging.

Moreover, a toughening of regulations concerning the issuing of work visas for visiting nationals from outside the EU/European Economic Area has caused problems for some festivals, galleries and other presenters. Although the government agreed that creative workers coming to the UK for less than three months will not require work visas (though they still require a sponsor), for those seeking a visa to stay longer the requirement for biometric information, including fingerprinting, has meant that the processing in some originating countries takes much longer even if a visa is approved, which has made it almost impossible for presenters to arrange short notice replacements from overseas, e.g. to replace a performer who is taken ill or is indisposed.

Concerns have also been expressed by the arts community about the entry conditions and criteria governing visas for up to 12 months for temporary workers (Tier 5) and visas for longer periods (Tier 2) (see also chapter 2.3). Representations from the National Campaign for the Arts and others in the arts and entertainment sector have resulted in some modifications to the visa process, but concerns remain that the process of inviting overseas artists is time consuming and expensive, as well as inhibiting.

Partly to address the number of occasions when notable creative people have been refused visas, Arts Council England was given the authority, from August 2011, to determine whether an individual qualified for admission to the UK on the basis of whether he/she were internationally recognised as a leader in their field under a new category of “exceptional talent” (Tier 1). Similarly, the Producers Alliance for Cinema & Television was given the role of assessing visa applications from the film, TV, animation, post-production and visual effects sectors. In 2018 the scope of “exceptional talent” visas was extended to include fashion designers and a wider pool of film and TV sector applicants. Moreover, the new Government’s intentions to toughen visa rules in the light of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU is also very likely to adversely impact on European mobility and interaction with the UK.