1. Cultural policy system

Belgium

Last update: November, 2020

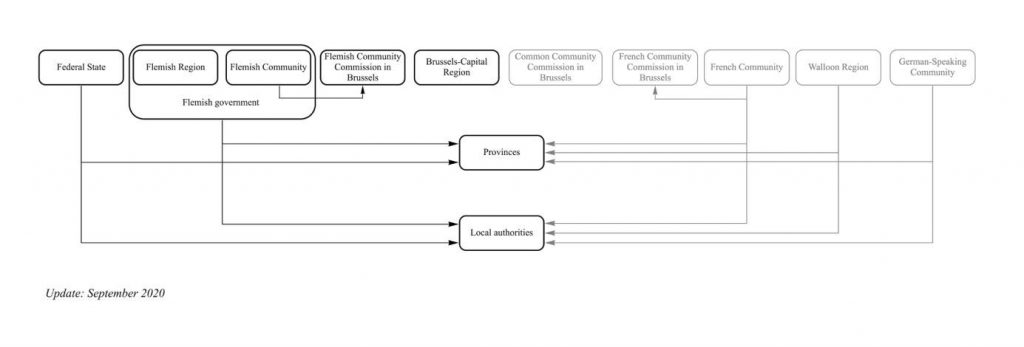

Belgium is a federal country, in which cultural affairs are mainly the subject of policies on the level of the Flemish, French, and German-speaking Communities (see 1.2.3). Cultural affairs refer to areas such as arts, heritage, language, media, youth policy, and sports (see 4.1.1). Tourism and immovable heritage are competences of the Regions (Flemish, Walloon, and Brussels-Capital Region; see 1.2.3). A number of (large) cultural institutions resides with the competences of the Federal State (see 1.2.2).

Principles of political and cultural democracy and references to human rights pervade the history of cultural policies in Belgium and its Communities. Many actions conducted in the framework of these policies are in line with the principles of the Council of Europe on the promotion of cultural diversity and cultural participation, respect of freedom of expression and association, and support of creativity. (Belgium played an active role in the history of the Council.) Another important principle underpinning a large deal of cultural policies in Belgium and its Communities is subsidiarity — or, the principle that the state does not directly intervene in cultural matters, other than by means of general regulations and support measures. Many cultural policy instruments are devised as subsidies for non-governmental organisations and non-profit players.

In this profile, we will focus on the cultural policies of the Flemish Community (which applies to people and organisations living and working in Flanders and Brussels) — more specifically: the policies subsumed under the Flemish policy field of Culture. This spans arts, heritage, socio-cultural work, circus, amateur arts, sign language, and policies that permeate these different fields. If relevant, we will refer to cultural or culture-related affairs that are subsumed under other policy fields of the Flemish Community (such as Youth and Media), or that are competences of the Flemish and Brussels-Capital Region (such as Immovable Heritage, Tourism, Economy, and Foreign Affairs) or the Federal State (such as Federal cultural institutions, Social Security, and Development Cooperation). This profile also deals with general trends in local cultural policy in Flanders and Brussels (see 1.2.4). Specific cases of local cultural policies will only be mentioned in this profile when relevant to a topic. Provincial authorities played a historical role in shaping cultural policy in Flanders, but are now largely divested from cultural competences (see 1.2.4).

In general, cultural policy in the Flemish Community is based on the following values:

- equal rights for all its inhabitants

- quality and diversity of the cultural offer (and taking measures to correct market distortions)

- cultural democracy and cultural participation

- cultural competences

- creativity

- protection and promotion of cultural heritage

Core responsibilities of the Flemish authorities with regard to the competence of Culture are:

- developing a strategic conceptual framework for cultural policies

- providing a set of policy instruments

- taking measures to increase the quality of the cultural offer and provision of cultural services

- monitoring (the effects of) these policy frameworks and instruments

A look at the historical background[1] elucidates how this complex policy structure and the principles that imbue it came about:

- 1944-1970: After the Second World War, cultural policies in Belgium expanded and were shaped by a drive to democratize culture — inspired by principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In line with international developments, cultural policies developed as an alternative to both the state culture of Communist countries and the market-governed system of the United States. These developments converged with the way Belgian society was historically shaped by philosophical and political divisions (the so-called ‘zuilen’, literally ‘pillars’), leading to the subsidiary government intervention in cultural affairs as described above.

- 1970-1980: The autonomy of the linguistic communities vis-à-vis the Federal State was further institutionalised. Cultural policy was divided over the newly created government levels. In the wake of these reforms, the Culture Pact (see 4.1.2) was passed. Throughout this decade, the ministers of Dutch Culture (as it was called) were Christian-Democrats, whose policies were geared towards democratizing culture (a network of culture centres and libraries was built throughout Flanders). In 1980, the Flemish and Walloon Regions were created (the Brussels-Capital Region followed in 1989), which also took up culture-related competences.

- 1981-1992: In the wake of economic turmoil, overall government expenditure on culture decreased. A new, rather management-oriented style of cultural policies — which included encouraging cultural organisations to generate a private income — was introduced by Liberal ministers of Culture in the Flemish government.

- 1992-1999: Christian-Democrat ministers of Culture continued the line of their liberal predecessors and focussed on the traditional arts and on socio-cultural work. Legislation on performing arts, music, and museums in Flanders and Brussels was passed that provided funding for delineated periods of time and which allowed funded players to devise longer-term planning.

- 1999-2009: Flemish government budgets for Culture increased considerably. Legal frameworks were streamlined and ‘integrated’ policies were created for the professional arts (the Arts Decree, which replaced discipline-specific regulations), cultural heritage (the Cultural Heritage Decree), and socio-cultural work (the Decree Socio-Cultural Work for Adults). The Funds for literature and for audiovisual production were also established in this period, as well as the Participation Decree (see 6.1).

- 2009-2020: Budgets for Culture came under pressure (see 7.1.2) and the number and scope of new policy initiatives on the Flemish level were rather limited compared to the preceding decade. As result of a reform of government levels and their remits in Flanders, local cultural policy was decentralised and provincial authorities were largely divested of their cultural competences. In the wake of these reforms, a new Decree on Supralocal Cultural Activities was established (see 1.2.4).

The previous five years of cultural policies and affairs constitute the main scope of this profile, with excursions to debates and policy initiatives of (roughly) the ten preceding years. This means we will refer to the terms of Bert Anciaux (Leftist-Liberal, in 2004-2009; this was his second term, after 1999-2002, when he was member of the Flemish nationalist Volksunie), Joke Schauvliege (Christian-Democrat, in 2009-2014), Sven Gatz (Liberal, in 2014-2019), and Jan Jambon (of the Flemish nationalist N-VA, 2019-2024).

[1] This section is an edit of similar sections in previous Compendium profiles on Belgium. For comprehensive overviews and analyses of (the history of) cultural policy in Flanders and Belgium, see: Laermans, Rudi. 2002. Het cultureel regiem : cultuur en beleid in Vlaanderen. Tielt: Lannoo; De Pauw, Wim. 2007. Absoluut modern: cultuur en beleid in Vlaanderen. Brussel: VUB Press; Van der Hoeven, Quirine. 2012. Van Anciaux tot Zijlstra. Cultuurbeleid in Nederland en Vlaanderen. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau; De Kepper, Miek. 2017. Over Bach, cement en de postbode. 50 jaar lokaal cultuurbeleid. Kalmthout: Pelckmans.

Last update: November, 2020

Belgium is a federal country. After six state reforms (in 1970, 1980, 1988-89, 1993, 2001, and 2012-2014), the Communities and Regions (see 1.2.3) hold a clearly defined set of competences (including, in the case of the Communities, Culture; see 1.1). The Federal State, which currently stands on the same hierarchical level as the Regions and Communities (see 1.2.1), still holds a number of important competences. Its legislation and policies apply to the whole territory of Belgium. Some of these are relevant when discussing cultural policy in Flanders and Brussels and pertain to social security, labour legislation, tax laws, or intellectual property rights (see 4.1). The legislative power on the Federal level resides with the Federal Parliament, which consists of two chambers: the Chamber of Representatives and the Senate. The Federal Government has the executive power. It is made up of ministers and secretaries of state.

A number of cultural institutions still fall under the competences of the Federal level. There are three Federal Cultural Institutions: Centre of Fine Arts BOZAR, La Monnaie/De Munt (the National Opera House), and the Belgian National Orchestra. Sophie Wilmès (since 2019) is currently the responsible minister. Then there are the Federal Scientific Institutions, such as the Royal Museums of Fine Arts, the Royal Museums for Art and History, the Royal Museum for Central Africa, the National Library (KBR), the State Archives, or the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. These reside with Science Policy, of which Thomas Dermine (since 2020) is currently the minister. Through Science Policy, a number of ‘Bi-Community cultural organisations and activities’ are funded (such as CINEMATEK, Europalia, and the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel) and a number of international organisations (such as Jeunesses Musicales International and ICCROM).

Last update: November, 2020

In federal Belgium, the Communities and Regions hold a defined set of competences vis-à-vis the Federal State. These levels of government are on the same hierarchical footing (see 1.2.1). In general, matters relating to the individual (which include Culture) reside with the Communities and matters relating to the territory (which include Immovable Heritage) with the Regions. Both Regions and Communities hold legislative and executive powers.

There are three Communities:

- The Flemish Community, which spans the territory of Flanders and Brussels

- The French Community, which spans the territory of Wallonia and Brussels

- The German-speaking Community, which spans a number of communes in the east of Wallonia

There are three Regions:

- The Flemish Region (which spans Flanders, but excludes the Brussels municipalities)

- The Brussels-Capital Region (which spans the nineteen Brussels municipalities)

- The Walloon Region (which spans Wallonia)

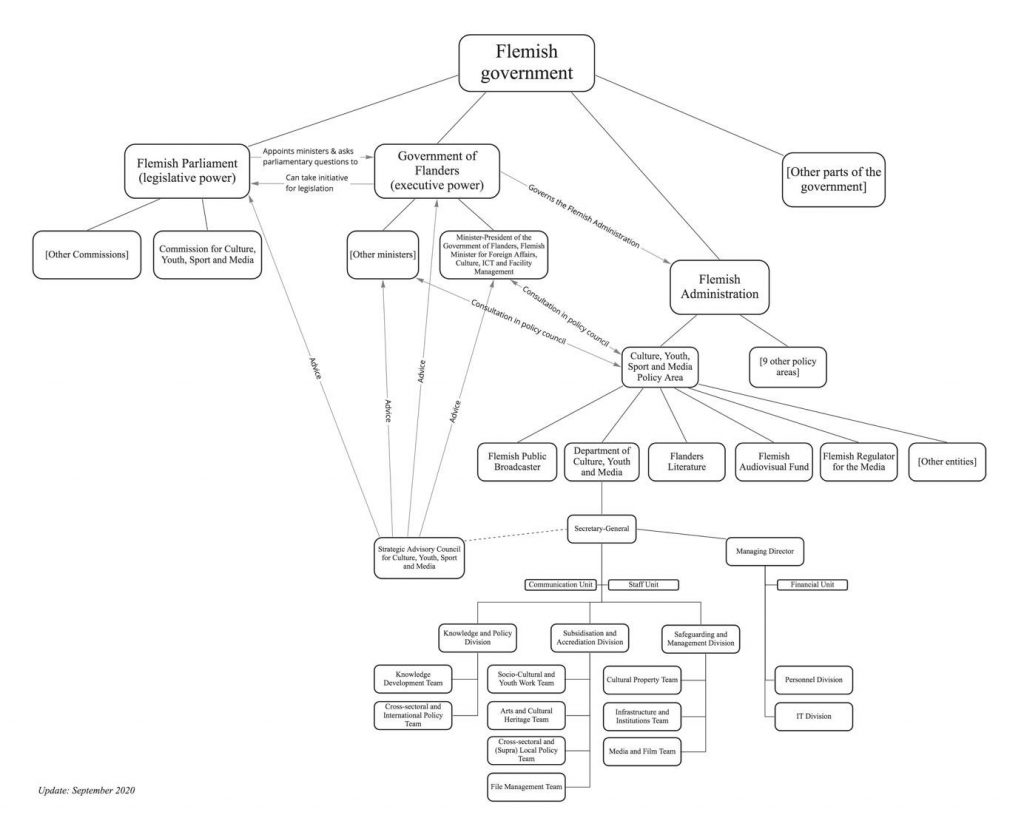

The powers of the Flemish Community and the Flemish Region are exercised by a single Flemish government (see 1.2.1). Within the government, the Flemish Parliament is the legislative body and the Government of Flanders (‘Vlaamse Regering’) holds the executive power. Legislation on this level is called a ‘decree’. A coalition agreement is made during negotiations for a new government, which contains the Government of Flanders’ resolutions for the coming term. Each minister then publishes policy memorandums, which lay down the goals in a specific policy field. In addition to the policy memorandum on Culture, the minister provides a more detailed account of policy objectives with regard to arts and cultural heritage in separate Strategic Vision Statements. Since 2020, each minister annually informs the Parliament of his or her policy goals and the planned allocation of funds by way of a formal explanation. In the current Government of Flanders (2019-2024), Jan Jambon is minister of Culture — next to being Minister-President and minister of Foreign Affairs, ICT, and Facility Management. Benjamin Dalle is minister of Youth and Media. Matthias Diependaele is minister of Immovable Heritage.

The services of the Flemish government administration are grouped in ten policy areas, including Culture, Youth, Sport and Media. Within this area, several bodies provide services with regard to the policy field of Culture. Among them, there is the Department of Culture, Youth and Media, which handles the preparation, follow-up, and evaluation of Flemish policies on culture, youth, and media. This includes administering the implementation of a large deal of cultural legislation, such as the Arts Decree, the Cultural Heritage Decree, or the Decree Socio-Cultural Work for Adults. Ministers and senior officials of the different administration services consult each other in policy councils.

Political primacy is an important principle in Flemish cultural policies. When policy instruments are devised or decisions are made on the support provided by these instruments, the final decision is mostly done by the minister and the Flemish government. However, the minister is advised by special bodies and the government administration. If s/he rejects this advice, the minister must provide a justification for doing so. One can discern two types in the advisory system: strategic policy advice and advice on the allocation of funding.

There is a Strategic Advisory Council for Culture, Youth, Sport and Media (SARC), which gives advice with regard to policy proposals and planned legislation — either on its own initiative or on request — to (the ministers of) the Government of Flanders or the Flemish Parliament. The SARC consists of independent experts and representatives of civil society. Its workings are integrated into the Department of Culture, Youth, and Media. Apart from a general council, there are subcouncils for Arts and Heritage, Socio-Cultural Work, Media, and Sports.

The basis of procedures for assessing the quality of funding applications in (e.g.) the arts, cultural heritage and socio-cultural work for adults is a combination of peer-review — by independent experts from the field — and review by the government department — of the administrative quality of the application. The result are advices on and rankings of applications, which the minister may follow in his/her decisions on granting subsidies.

There are exceptions to the principle of political primacy. There are entities involved in implementing policies in the area of Culture, Youth, Sport and Media that have a degree of autonomy, such as the funds for literature (Flanders Literature; see 3.5.2) and audiovisual production (Flemish Audiovisual Fund, or VAF; see 3.5.3). These entities sign management agreements with the Flemish government.

It should be noted that the competences of the Brussels-Capital Region do not wholly exclude Culture. Similar to the other Regions, it can of course devise policies with regard to Immovable Heritage (Pascal Smet is the responsible secretary of state). But as a result of the Sixth State Reform (2012-2014), it now also holds the competence of ‘Bi-cultural Matters of Regional Significance’ (Rudi Vervoort, who is Minister-President, is responsible). Though there is discussion about the exact definition of these matters, this new competence more or less means that the Brussels-Capital Region can devise policies for cultural institutions that neither fall under one of the Communities, nor under the Federal State, nor under the local authorities. This also means the Brussels-Capital region can establish its own cultural institutions.[1]

[1] One result of this new competence is KANAL, which involves a partnership with the French Centre Pompidou. The foundation of this new museum has caused debate among professionals from the Cultural field in Brussels (see, for example, the reports of a conference in 2018 on the topic).

Last update: November, 2020

There are ten provinces and (at the time of writing) 581 communes in the whole of Belgium. Five provinces are located in the Flemish Region. These comprise 300 communes, of which thirteen are officially acknowledged as ‘centre cities’ (‘centrumsteden’; this status has an effect on, e.g., their funding). There is no provincial authority sensu stricto in the Brussels-Capital Region, which spans 19 different communes. In the hierarchy of government levels (see 1.2.1), provincial and local authorities constitute the lower levels. Both have a large degree of autonomy over the competences they each exert within their territories. They can devise policy instruments and allocate resources to these. Local authorities in the Flemish Region can, for example, set up their own support schemes for local cultural and leisure time initiatives.

Provincial and local authorities, however, are bound to the general legislation and regulations on the level of the Federal State and the Communities and Regions under which they reside. They are monitored by and receive funding from these higher levels of government (especially the Regions). The Municipal Fund is the most important source of funding for local governments.[1] The Association of Flemish Cities and Municipalities (VVSG) acts as an advocacy organisation, expertise provider, and network for local governments in the Flemish Region. There is also an Association of the City and the Municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region (VSGB). The Association of Flemish Provinces (VVP) provides similar services for the Flemish provinces.

Both provinces and local authorities have played a historically important role in establishing a cultural offer in Flanders, if not complementary with higher levels of government (see also 1.3.1 and 1.3.3). A landmark was the creation of cultural centres and libraries throughout Flemish communes. This process took off in the 1960s — with, e.g., policies stimulating local governments to start building cultural centres — and continued in the 1970s and afterwards (see also 1.1). This resulted in a substantial network of local cultural infrastructure (see table 1 in 1.3.2 for figures).[2]

As a consequence of the ‘Internal State Reform’, the role of the lower governments in Flanders with regard to cultural policy has changed significantly.[3] Since 2018, provincial authorities have been divested of most of their cultural competences (such as providing multi-year funding for cultural organisations). The culture budgets of the provinces have been divided among the Flemish government and the local authorities. Provinces still have some limited competences with regard to Immovable Heritage (see 3.1).

Since 2016, local cultural policy has been largely decentralised.[4] Resources for local cultural centres and libraries — which used to be regulated through the Decree on Local Cultural Policy — were integrated into the Municipal Fund. Contrary to the situation under the Decree on Local Cultural Policy (see also 4.1.2), funding through the Municipal Fund is no longer earmarked for specific fields such as culture. At the same time, the conditions for obtaining these funds have changed and the obligation for libraries and cultural centres to report their activities to the Flemish government has ceased (causing a gap in the data). The responsibility for conducting a local cultural policy now fully resides with the local authorities, with the Flemish government taking up a supportive and stimulating role — rather than a steering and controlling role. It is not entirely clear what the effect of these changes has been on local funding for arts and culture, but the overall expenditure on culture and culture-related matters by the lower government levels remains substantial (see 7.1.2[5]).

In 2019, in the wake of these governmental reforms, a Decree on Supralocal Cultural Activities came into effect. Through this new legislative framework, the Flemish government aims to stimulate collaboration between players of different cultural disciplines (or collaboration between players in culture and other spheres), beyond the borders of communes. The Decree offers project funding for cultural organisations, multi-year funding for inter-municipal partnerships involving culture, and a centre of expertise (OP/TIL) aimed at supporting projects and partnerships.

Lastly, we should mention the Flemish Community Commission (VGC). This separate level of government (see 1.2.1) is responsible for competences of the Flemish Community — among them Culture — in the Brussels-Capital Region. Its responsibilities, however, are limited to institutions that are connected with the Flemish Community (such as libraries, community centres, or schools). These responsibilities are in part derived from Flemish Decrees — this way, the VGC acts as if it were a ‘provincial’ or ‘local’ authority for Flanders — but it can also supply in complementary policies — it for example provides funding for arts organisations or artistic projects. The Flemish government monitors the workings of the VGC and has, under certain conditions, the authority to revoke its decisions. The VGC consults official and advisory councils and panels with regard to its competences, such as Culture. These consist of independent professionals.

[1] Belfius. 2016. ‘Gids: hoe werkt een gemeente?’, 34.

[2] De Kepper, Miek. 2017. Over Bach, cement en de postbode. 50 jaar lokaal cultuurbeleid. Kalmthout: Pelckmans, 53-92.

[3] Agentschap Binnenlands Bestuur van de Vlaamse overheid. 2011. Witboek interne staatshervorming, 73.

[4] In communes with linguistic facilities (see also 2.5.4) bordering Brussels-Capital Region, this reform took place in 2018.

[5] Note that the figures in table 6 refer to expenses by all lower government levels (i.e. local authorities + provinces) in the whole of Belgium (not only the Flemish Region).

Last update: November, 2020

Sections 1.2.3 and 1.2.4 mention official advisory bodies that consist of independent professionals and that provide advice on cultural policy matters of the Flemish Community: the Strategic Advisory Council for Culture, Youth, Sport and Media (SARC), the commissions for peer-review of funding applications, and the advisory councils and panels of the Flemish Community Commission (VGC). These show how consultation of non-governmental actors is structurally embedded in the workings of the Flemish cultural policy system.

Beside the functioning of these advisory bodies, there are advocacy organisations and labour unions that aim to represent the voice and interest of the different players in the cultural field (see 7.2.4 for examples of associations and unions in the professional arts). These of course do not wholly exclude the possibility of cultural organisations or artists individually lobbying policy makers. Funds for subsistence security (see 7.2.2) sometimes also make their voice heard in (public) debates on cultural matters.

The independent centres of expertise (‘steunpunten’; see 7.2.1) can be called upon by the Flemish government to provide advice or expertise with regard to certain policy initiatives. Flanders Arts Institute, for example, provides a “Landscape Sketch of the Arts”, a (strategic) analysis of trends in the professional arts in Flanders and Brussels that serves as input for the Strategic Vision Statement of the Arts of the minister of Culture (this is codified into the Arts Decree, art. 7). Ministers of Culture have also gathered centres of expertise, advocacy organisations, and other professional cultural players in ad hoc working groups or consultation rounds on specific topics, such as fair practices (see 2.3), combatting harassment and abuse (see 2.5.5), ecological sustainability (see 2.8), or changes in the legal framework (see 2.9).

There have been several (usually small-scale) experiments in Belgium with deliberative democracy. A notable example from the field of Culture are the ‘citizen cabinets’ (Burgerkabinetten) that minister Sven Gatz (2014-2019) organized to gather input for his policies. The ideas that resulted from the citizen cabinet on culture were much in line with existing policies and initiatives from the field.[1]

[1] Bamps, Hadewych, Michiel Nuytemans, Annemie Rossenbacker, and Jo Steyaert. 2015. ‘Burgerkabinet. Rapportering resultaten’. Levuur/Indiville/Tree Company, 85-86.

Last update: November, 2020

Decisions of the Government of Flanders (‘Vlaamse Regering’) are made as a result of consensus between its ministers, who meet on a weekly basis. There is regular consultation and cooperation among the different entities of the government administration. The Department of Culture, Youth and Media (see 1.2.3), for example, cooperates with the Flanders Department of Foreign Affairs (see 1.4.1), VISITFLANDERS (see 3.5.6), the Ministry of Education and Training (see 5.1), or other administration services dealing with Equal Opportunities Policies (see 2.5.1, 2.5.6, and 2.6). It also works together with other entities within the Flemish government, such as the Flemish Ombudsman Service (see 2.5.5).

Consultation between the Federal State and the Communities and Regions in Belgium happens in an Intergovernmental Committee. Here, policies are geared to one another, cooperation agreements are defined, and conflicts of interest between the governments are settled. From within this Committee, the topics for specific Inter-Ministerial Conferences are decided. In the Inter-Ministerial conference on Culture, the ministers of this policy field from the different governments meet. This currently includes minister Jan Jambon, his counterparts in the French and German-speaking Communities, the Brussels minister for Bi-cultural Matters (see 1.2.3), the Federal ministers mentioned in 1.2.2., and members of the executive boards of the Flemish (VGC, see 1.2.4) and French Community Commissions in Brussels. Current topics include the impact of COVID-19 on cultural sectors, the regulations for artists in the social security framework (the ‘kunstenaarsstatuut’, see 4.1.3), and tax shelter regulations (see 4.1.4).

In 2012 — after a long period of preparation and negotiation — a cooperation agreement was signed between the Flemish and the French Communities. This provides the framework for exchange of expertise between these levels of government and support schemes for cultural projects that involve cooperation between organisations in both Communities. A cultural programme with the German-speaking Community was set up for the period 2019-2021. This includes similar project support, but also literary residencies and exchange of expertise on heritage (see also 1.4.1).

There are different legal frameworks in Flanders for cooperation between local authorities. With regard to the policy field of Culture, we should mention the Cultural Heritage Decree — which allows for the funding of inter-municipal covenants in providing services with regard to cultural heritage — and the new Decree on Supralocal Cultural Activities (see 1.2.4).

Last update: November, 2020

Flanders has been described as a cultural ‘nebular city’, a sprawl of predominantly small to mid-large cultural infrastructure and organisations of private and public origin.[1] The distinction between both is not always clear, as some public organisations are former private initiatives and private organisations may have received some form of public support at some point in their history. The Flemish Arts Decree, for example, has provided a relatively flexible framework that allows organisations with a predominantly private income structure (such as music clubs) to apply for public funding. Many publicly funded socio-cultural organisations also rely for a large part on private sources of income.

(Ameliorating the conditions for) private funding was one of the key policy themes during the term of former Flemish minister of Culture Sven Gatz (2014-2019) (see 7.3). It remains a focus under current minister of Culture Jan Jambon (2019-2024). In his recent Strategic Vision Statements for the Arts, Jambon stressed that the cultural sector is to be seen as part of a broader market economy and that subsidized actors should organise and sell their work according to the market value.[2]

[1] Davidts, Wouter. 2004. ‘Vlaanderen Culturele Nevelstad: culturele infrastructuur in een horizontaal verstedelijkt landschap’. In Jaarboek Architectuur Vlaanderen 02-03, Antwerpen: Vlaams Architectuurinstituut (VAi), 71–79.

[2] Jambon, Jan. 2020. ‘Strategische Visienota Kunsten’, 16-17.

Last update: November, 2020

Table 1 provides the most recent numbers of selected types of cultural institutions. Immovable heritage sites and archaeological sites are a competence of the Flemish Region (thus excluding the territory of the Brussels-Capital Region) and fall under a different policy area than the other mentioned institutions. Museums, archives, and other organisations receiving multi-year (‘structural’) funding through the Cultural Heritage Decree (95 in total [1]), the arts organisations with structural subsidies through the Arts Decree (performing arts, music, visual arts, architecture and design, and transdisciplinary and multidisciplinary arts; 215 in total[2]), and the organisations structurally supported through the Decree Socio-Cultural Work for Adults (126[3]) are seen as part of the Flemish Community (which spans both Flanders and Brussels).

Public libraries and local cultural centres[4] (the figures presented refer to Flanders and Brussels) are now fully under the responsibility of local governments (see 1.2.4). Although culture is, strictly seen, not one of its competences, the Federal Government provides funding to some important cultural institutions. These fall under different official categories: ‘Scientific Institutions’, ‘Cultural Institutions’, and ‘Bi-Community cultural organisations and activities’ (see 1.2.2 for further details).

There is one Flemish Public Broadcaster (VRT), which includes television and radio broadcasting). This is complemented by a number of licensed private television companies. Then there smaller, regionally organised public television organisations throughout Flanders. In radio broadcasting, there are, next to VRT, numerous licensed private and local stations active.

Table 1 also counts cinemas in Flanders and Brussels. These are predominantly private: the Flemish government does not provide funding specifically aimed at cinemas, but some do receive support from other levels of government.

Table 1: Cultural institutions, by sector and domain

| Domain | Cultural institutions (subdomains) | Public sector | Private sector |

| Number (year) | Number (year) | ||

| Cultural heritage | Immovable heritage sites (protected) in Flemish Region (excluding protected archeological sites) | 13 725 (2020) | / |

| Archaeological sites (protected) in Flemish Region | 46 (2020) | / | |

| Museums | Museums institutions structurally funded through Cultural Heritage Decree | 45 (2020) | / |

| Archives | Archive institutions structurally funded through Cultural Heritage Decree | 9 (2020) | / |

| Visual arts | (Audio-)visual arts organisations structurally funded though Arts Decree | 25 (2020) | / |

| Performing arts | Performing arts organisations (theatre, dance, musical theatre) structurally funded through Arts Decree | 70 (2020) | / |

| Music organisations (classical music, jazz, folk, pop and rock) structurally funded through Arts Decree | 59 (2020) | / | |

| Libraries | Public libraries | 314 (2015) | / |

| Audiovisual | Cinemas in Flemish and Brussels-Capital Regions | / | 43 (2018) |

| Flemish public broadcasting organisation (VRT) | 1 (2020) | / | |

| Regional television broadcasting organisations | 10 (2020) | / | |

| Flemish private television broadcasting organisations | / | 16 (2020) | |

| Flemish private radio broadcasting organisations | / | 3 (2020) | |

| Network radio broadcasting organisations | / | 61 (2020) | |

| Local radio broadcasting organisations | / | 236 (2020) | |

| Interdisciplinary | Transdisciplinary organisations structurally funded through Arts Decree | 8 (2020) | / |

| Multidisciplinary organisations structurally funded through Arts Decree | 39 (2020) | / | |

| Other | Architecture and design organisations structurally funded through Arts Decree | 7 (2020) | / |

| Art institutions funded through Arts Decree | 7 (2020) | / | |

| Organisations structurally funded through Cultural Heritage Decree, other than museums and archive institutions | 41 (2020) | / | |

| Organisations structurally funded through the Decree Socio-Cultural Work for Adults | 126 (2019) | / | |

| Local culture centres | 69 (2015) | / | |

| Federal Scientific Institutions | 10 (2020) | / | |

| Federal Cultural Institutions | 3 (2020) | / | |

| Federally funded Bi-Community cultural organisations and activities | 9 (2020) | / |

Sources:

Department of Culture, Youth and Media of the Flemish government, Flanders Heritage, Flemish Regulator for the Media, and Statbel.

[1] FARO made an online overview of organisations funded through the Cultural Heritage Decree and other organisations dealing with cultural and immaterial heritage in Flanders and Brussels. An online inventory of immaterial heritage practices is provided by Workshop Intangible Heritage Flanders. See also 3.1.

[2] These organisations are included — together with private initiatives and individual artists in Flanders and Brussels — in the online databases of Flanders Arts Institute. For an analysis of trends in the number of organisations with multi-year funding through the Flemish Arts Decree, see: Leenknegt, Simon. 2020. ‘Structurele subsidies via het Kunstendecreet - Kunsten.’ Kunsten.be.

[3] Socius has an online database of organisations for socio-cultural work for adults.

[4] 'Culture centres' (or 'cultuurcentra') were until 2016 an official category, used to denominate local cultural institutions in municipalities all over Flanders. (These were funded in a different way than the 'community centres' or 'gemeenschapscentra', which are not included in table 1.) The number of institutions in 2015 is still the same in 2020, but the legal framework (and funding modalities) have changed.

Last update: November, 2020

Public cultural infrastructure in Flanders (the so-called ‘nebular city’, see 1.3.1) is in large part a result of the interplay between the Flemish Community, the provinces, and local authorities. This balance has changed in recent years, however, as a result of the ‘Internal State Reform’ (see 1.2.4). This divested the provincial governments of most of their cultural competences and intensified a decentralisation of local cultural policy in Flanders. The lower levels of government nonetheless remain an important provider of funding for cultural and culture-related initiatives (see also 7.1.2).

A substantial part of the funding of cultural organisations by the Flemish government is respectively arranged through the Arts Decree, the Cultural Heritage Decree and the Decree Socio-Cultural Work for Adults. Opportunities are also provided by the Participation Decree (see 6.1) and, since 2019, the Decree on Supralocal Cultural Activities (“Decreet Bovenlokale Cultuurwerking”, see 1.2.4). Through this new legislative framework, the Flemish government aims to stimulate collaboration between players of different cultural disciplines (or collaboration between players in culture and other spheres), beyond the borders of municipalities. The Decree on Supralocal Cultural Activities offers project funding for cultural organisations, multi-year funding for intermunicipal partnerships involving culture, and a centre of expertise (OP/TIL) aimed at supporting projects and partnerships. Funding through these various decrees has been subject to budget cuts during the current and previous legislative sessions (see also 7.1.3).

Until recently, a group of major cultural institutions with a close relationship to the Flemish government (‘Instellingen van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap’) was excluded from existing decrees. The legal framework on the funding and governing of most of these organisations has been integrated into the Arts Decree and the Cultural Heritage Decree, giving rise to new official categories: ‘art institutions’ or ‘kunstinstellingen’ (such deSingel, Ancienne Belgique, or Opera Ballet Vlaanderen) and ‘cultural heritage institutions’ (currently only one, the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp). Each of these sign an official management agreement with the Flemish government and is subject to specific procedures of quality assessment.[1]

Though also affected by budget cuts, these major institutions have been spared more than other organisations and even saw a steady increase in overall funding throughout the years. Both the former and the current minister of Culture championed them as “ambassadors” and as serving as models for others.[2] Under Sven Gatz (2014-2019) the group of art institutions was expanded with two more organisations (Vooruit and Concertgebouw Brugge). Current minister Jan Jambon (2019-2024) announced he would introduce a new category of funding for major institutions (‘kerninstellingen’), similar to the art institutions (see 2.3 and 2.9).[3]

[1] There has been debate on the position and role of major art institutions in the (subsidised) arts field, see Overbergh, Ann, Katrien Kiekens, and Dirk De Wit. 2019. ‘First among equals? The art institution today’.

[2] Gatz, Sven. 2014. ‘Beleidsnota 2014-2019. Cultuur’, 11 and 18; Jambon, Jan. 2019. ‘Beleidsnota Cultuur 2019-2024’, 15.

[3] Jambon, Jan. 2020. ‘Strategische Visienota Kunsten’, 8.

Last update: November, 2020

Both the Federal State and the Communities and Regions have competences in foreign relations. The latter can devise policies on foreign affairs, but only with regard to their own competences (this is the principle of “in foro interno, in foro externo”). This means the Flemish government can sign agreements with (foreign) regions and other countries than Belgium.[1]

Culture is deemed an important topic in the international relationships of the Flemish government. A significant part of government policies on international cultural cooperation can be described as being governed by the principle of ‘follow the actor’, in which especially players from the cultural field take the initiative (see 1.4.3).

The Flanders Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA)[2] acts as a bridge between the cultural field and the network of General Representatives of the Government of Flanders. This network consists of thirteen diplomatic representatives in other countries or in international bodies such as the Council of Europe, UNESCO, the UN, or the OECD. Part of their job is to enhance the international visibility and reputation of Flanders through the arts and heritage sector. The General Representatives can support cultural partnerships and events involving cultural players from Flanders and abroad. The FDFA also provides support for cultural projects that share the interests of the Flemish government (for example on topics related to human rights) or that help fostering relations with other regions and countries. The FDFA represents Flanders in the EUNIC network.

For matters related to culture, the FDFA consults the Department of Culture, Youth and Media (see 1.2.3 and 1.2.6), VISITFLANDERS (see 3.5.6), and Flanders Investment & Trade (see 3.5.1). There is also collaboration on international cultural partnerships with the centres of expertise (see 7.2.1), the funds for literature (see 3.5.2) and audiovisual arts (see 3.5.3), and museum associations (see 3.1) through the platform Flanders Culture.

There is no network of publicly mandated cultural institutes, except for Arts Flanders Japan (a Liaison Office of the Government of Flanders for cultural affairs) and De Brakke Grond. The latter is a cultural centre established by the Flemish government in Amsterdam in 1981. Its mission is to promote the cultural identity of Flanders, offer a stage for artistic developments from Flanders, and promote Dutch-Flemish cooperation.

The Netherlands has been a preferred partner in bi-lateral cultural collaboration since long — and especially so for current minister of Culture Jan Jambon (2019-2024; see 2.5.4). Both governments, for example, founded deBuren in 2004. It is a cultural organisation seated in Brussels that organises cultural projects and debates on culture, society, and politics in the Low Countries. Next to exchange and cooperation between Flanders and the Netherlands, there is also joint action in establishing external relationships. An important example is the Union for the Dutch Language or Taalunie, which is the result of a treaty between the Flemish and Dutch Governments in 1980. This intergovernmental organisation (Suriname is also an associate member since 2004) has reconsidered its mission over the years and focuses now on developing and promoting policies on Dutch, promoting the Dutch language in other countries, and hosting a network of experts on language-related matters.

Other partners for intense bi-lateral collaboration are the French Community in Belgium (see 1.2.6) and Morocco (since 1975). The governments of Flanders and Morocco together founded Darna, with the aim of stimulating cultural interaction between the Flemish and Moroccan communities in Flanders and Brussels. This cultural house in Brussels organises events and supports projects that contribute to this goal. Other, more recent, bi-lateral cultural cooperation partnerships were established with (among others) the Hauts-de-France region in France (2018-2021), China (2019-2022), and the German-speaking Community in Belgium (see 1.2.6).

Lastly, we should mention that cultural diplomacy initiatives are also undertaken on the Federal level, especially by the cultural institution BOZAR.

[1] The FDFA provides an overview of agreements with regard to culture (see also 4.2.1).

[2] This government department was at the time of writing in the process of merging with the Department of Public Governance and the Chancellery.

Last update: November, 2020

Belgium is a member state of the EU, Council of Europe, UN, UNESCO, and the OECD. The Flemish government is also involved in these intergovernmental bodies, either through independent relations, or through the Belgian membership (which requires coordination with the other government levels involved). This involvement includes implementing treaties and policies, financial support for the workings of these bodies, and participation in working groups or conferences. Carrying out and monitoring treaties and policies[1] is done by different ministers and administration services of the Federal and Flemish governments, such as the Flanders Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA; see 1.4.1) and the Department of Culture, Youth and Media (see 1.2.3 and 1.2.6). With regard to their competences (including Culture), the responsible ministers of the different Communities take on a rotating role in the Council of the European Union (this follows the principle explained in 1.4.1).

Creative Europe Desk Vlaanderen is the information desk on the Creative Europe programme for the Flemish Community. There is a separate national agency for the Erasmus+ programme in Flanders, namely Epos. There are also separate national UNESCO Commissions for the different Communities: the Flemish UNESCO Commission and the Commission representing both the French and German-speaking Communities. The Flemish government created two UNESCO Trust Funds, of which the general fund supports projects on cultural heritage (this is financed by the FDFA). The UNESCO Platform Flanders functions as an information desk for the Flemish Community.

With regard to the role of Flanders in the EU, we should mention the Liaison agency Flanders-Europe (VLEVA). This is a membership organisation that acts as a network and expertise provider for actors from civil society (such as advocacy associations) and for the different government levels in Flanders.

Lastly, we should mention that the Flemish government is a member of the Union for the Dutch Language, together with the Netherlands and Suriname (Taalunie; see 1.4.1).

[1] The FDFA provides an overview of international treaties with regard to culture in which the Flemish government is involved, including those of the Council of Europe, UNESCO, and UN (see also 4.2.1).

Last update: November, 2020

Transnational collaboration on developing and sharing work and projects is widespread among artists and organisations in the professional arts scene in Flanders and Brussels.[1] This exchange is in part facilitated by international network organisations in arts and culture — some of which have their main seat in Belgium, such as IETM, On the Move, the EFA, Pearle*, or Culture Action Europe (all of them in Brussels). In the cultural heritage field in Flanders and Brussels, international cooperation happens through membership of network organisations (ICOM, NEMO, etc.), engaging in the UNESCO networks, or participating in international (digitization) projects such as Europeana. Complementary to the mentioned international networks, the centres of expertise (see 7.2.1) play an active role in establishing relations between cultural professionals from Flanders and abroad.

Another impetus for professional cooperation beyond borders is provided by the framework of support measures. These include the EU support schemes (Creative Europe, Erasmus+, Europe for Citizens, Interreg, etc.), in which cultural organisations and professionals from Flanders and Brussels have participated throughout the years.[2] The Flemish government also provides a range of relevant funding options. Project funding, grants, multi-year subsidies arranged by the Arts Decree, for example, can be used for deploying international activities. Additionally, it supplies in a number of schemes specifically aimed at supporting international career development or mobility (see 7.2.1). Networks such as those mentioned above can apply for project funding through the Arts Decree. Outside the policy field of Culture, we could mention the support schemes of Flanders Investment & Trade (see also 3.5.1) that are applicable to international entrepreneurial activities in the CCI, such as participating in foreign art or design fairs.

Next to funding schemes that ‘follow the actor’, we could also refer to those mentioned in 1.4.1 as relevant for supporting international cooperation by cultural professionals and organisations — such as funding by the Flanders Department of Foreign Affairs or within the context of bi-lateral relationships. Here, the goals and geographical reach of projects are more strictly defined and fit into specific government strategies.

Current minister of Culture Jan Jambon (2019-2024) has mentioned (policies aimed at) internationalisation as a priority in his policy statements on arts and culture.[3]

[1] For a comprehensive analysis of international cooperation in the arts in Flanders and Brussels, see Janssens, Joris. 2018. (Re)framing the International. On new ways of working internationally in the arts. Brussel: Kunstenpunt. For facts and figures on international activities by artists and arts organisations, see Janssens, Joris, Simon Leenknegt, and Tom Ruette, eds. 2018. Cijferboek Kunsten 2018. Brussel: Kunstenpunt, 33-178.

[2] VLEVA (see 1.4.2) provides an overview of EU funding measures in which players from Flanders and Brussels were recently honoured.

[3] Jambon, Jan. 2019. ‘Beleidsnota Cultuur 2019-2024’, 28-31; Jambon, Jan. 2020. ‘Strategische Visienota Kunsten’, 15-16.