2. Current cultural affairs

Luxembourg

Last update: February, 2023

Many efforts have been invested since 2018 in changing the overall approach to the cultural sector, in challenging long established policy approaches and in rendering procedures more participatory, thus narrowing the gap between discussions within the sector, civil society and the policy level. In that process, a very strong focus is being put, on the one hand, on the professionalisation of the cultural and creative actors and on professional artists’ working conditions, whereas cultural heritage protection is the other predominant priority.

In terms of governance, significant emphasis is put on the participatory approach to cultural policies through the regular organisation since 2016 of cultural plenary meetings, the “Assises”. These give the sector many opportunities to point to difficulties or gaps in approaches and to input their views on topics or problems at hand on the policy level. The most notable result of this approach is the Cultural development plan 2018-2028 (KEP) that constitutes the first programmatic, supra-political document for medium term policy development in the cultural and creative sector.

The participatory process also applies outside the Assises, insofar as the sector and all other relevant actors are regularly consulted on measures and legislative matters during the phase of definition (this was even reinforced during the Covid19 pandemic). To that end, those sectors that had no unified representation so far, have been financially encouraged to assemble within federations or associations that could serve as representative interlocutor to the national authorities.

An important success with regard to cultural heritage protection is the adoption of a new cultural heritage law that represents a fundamental change of paradigm in the approach to heritage protection and preservation.

In the general context of the evolution of cultural policies in Luxembourg, an interesting role falls to the European Capitals of Culture. While the "designation of Luxembourg-City as European Capital of Culture in 1995 raised awareness of the lack of cultural facilities from which the country suffered"[1] and breathed new life into the professionalization of the sector, "Luxembourg and Greater Region, European Capital of Culture 2007” has heightened awareness of the cross-border aspect of creative production in this geographically limited space of Luxembourg. Audience development and participation, notably of the young, are also important aspects of the ECoC. Finally, the current Esch2022 project aims to become a driving force for the development of an entire region on both sides of the Franco-Luxembourg border.

[1] Kulturentwécklungsplang eBook 1.0 - Septembre 2018, Volume 1, p.49

Last update: February, 2023

Luxembourg’s constitution guarantees a certain number of fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression, individual freedom, right of association and the protection of the human and natural environment.

So far, cultural rights are not yet embedded in the constitution or in national legislation. Nevertheless, on the one hand, and in the context of the process currently underway to give the constitution a general revision, the introduction of an article relating to cultural rights is currently being analysed. Indeed, if adopted, a new article would foresee that the State guarantees access to culture, the right to cultural development and that it promotes the protection of cultural heritage.

On the other hand, and insofar as Luxembourg has signed and ratified treaties such as the Council of Europe’s European Cultural Convention and the UN’s International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the rights principles enshrined within these treaties are considered as fundamental basis for policies in general. Reporting obligations on the Covenant as well as on other treaties containing references to cultural rights provide for regular monitoring to that regard.

Concerning ethics, the ministry of Culture has issued in 2022 a Deontology charter for cultural structures. Following a demand from the cultural sector and as foreseen in the current Cultural development plan (KEP)[1], the charter aims to defend the values of ethics and professionalism that underlie the relationship of trust between cultural structures, artists and citizens. More specifically, it imposes fair and equitable remuneration of artists, the respect of data protection and professional secrecy, prevention of conflicts of interest, gender equality etc.

The charter was drawn up by the ministry of Culture in consultation with representatives of the cultural sector, whose feedback and reflections were received during discussion meetings and written positions. The charter applies to cultural structures which benefit from a specific budget line within the budget of the ministry of Culture and those who have signed a financial agreement with the ministry (other structures may sign it on a voluntary basis). Compliance with the charter’s rules forms part of the evaluation of the cultural structure’s activities by the ministry and the non-respect may lead to a reduction or a halt of financing from the ministry of Culture.

[1] "Establish a new mode of governance of cultural institutions under the supervision of the Ministry of Culture"

Last update: February, 2023

Although there are no policies or measures to promote exclusively and explicitly artistic freedom, the concept is very much at the core of the government’s policy in general and of every measure taken in favour of artists and creative professionals, notably in terms of creating social and economic conditions allowing them to work freely and independently.

An important element to that regard is the State support system for independent professional artists and intermittent workers. According to the amended law of 19 December 2014 relating to 1) social measures for the benefit of independent professional artists and intermittent workers and 2) the promotion of artistic creation, may indeed benefit from social assistance for a period of 24 months (renewable) on the provision that they fulfil prerequisites, such as being continuously registered in Luxembourg for at least 6 months prior to the request, having performed artistic services for at least 3 years etc. Intermittent workers in the entertainment industry, who alternate between periods of employment and periods of inactivity, are entitled to involuntary-out-of-work benefits, provided for instance that they have worked for at least 80 days over the course of the 365 calendar days prior to the application, that during that time they worked either for businesses, for any type of entertainment organiser or in the context of a production, etc.

Considering that certain of these provisions are no longer appropriate due to the evolution of the cultural sector in recent years as well as the evolution of the professionals’ working and living conditions (notably because of the Covid19 pandemic), an adaptation to this legislation has been submitted to Parliament in November 2021 by the ministry of Culture. The proposed amendments are the result of a dialogue between the various representatives of the artistic and cultural scene, launched at the end of 2019 by a public consultation, which aimed to launch reflections on the usefulness of such an adaptation. Consequently, changes applying to artists would comprise, for instance, the reduction of one year, or even the exemption (for university graduates) of the reference period preceding the application, as well as increase in the period of the benefit of aid and of the amounts of monthly aid. For intermittent workers, the scope will be broadened to include more professions and activities, the possibility of suspending the period of eligibility for aid (in the event of illness, maternity leave, parental leave, etc.) will be revised and adapted, etc.

In terms of artists’ mobility, the creation in 2020 of the arts council type Kultur|lx specifically aims to improve and increase the promotion of professional artists’ abroad and to improve abilities and capacities for their career development. This excludes however nonprofessional artists and focusses on specific countries that are being determined by Kultur|lx according to a market logic.

In complement to these measures, a draft bill has also been tabled early 2022 to reintroduce a cultural leave, modifying the Labour Code, the law establishing the general status of State civil servants and the law establishing the general status of communal civil servants. “The purpose of cultural leave is to allow participation in high-level cultural events or recognized events that are not part of the applicant's main professional activity, or to offer the possibility of participating in specialized training in the cultural field organized by an approved body. Three categories of persons may be granted cultural leave: cultural actors, administrative executives or persons designated by federations, national networks or associations in the cultural sector.”[1]

[1] https://gouvernement.lu/en/actualites/toutes_actualites/communiques/2022/01-janvier/27-conge-culturel.html

Last update: February, 2023

In accordance with successive governments’ transversal Digital Lëtzebuerg strategy, launched in 2014, the coalition agreement 2018-2023 of the current government puts much importance on the digitalisation of the cultural sector.[1]

Acknowledging both the necessity and labour-intensive nature of effectively managing digital collections, whether digitized- or digital-born, but also considering the paradigm shift that an increasingly digital society represents, the ministry of Culture put in place a digital strategy for cultural heritage in 2017.

Accordingly, the three main objectives of the strategy are: 1) Broad and inclusive access to digital cultural heritage, 2) Synergies between cultural heritage institutions, 3) A sustainable and quality-oriented digital cultural heritage ecosystem.

A 2017 survey on Luxembourg’s digital cultural heritage identified several challenges: strategic and financial planning; staffing and skills; documentation issues; technical infrastructure; accessibility of existing digital assets and rights related issues. Therefore, making the readiness by the ministry to take the strategic lead, by creating a service at policy level that supports and coordinates the digital evolution of the cultural heritage sector, all the more important and relevant.

Further reflections are ongoing to expand the ministry’s digital strategy to include the creative sectors. Certain elements are already in place such as funding schemes for digital art creation. This needs to be further embedded in the overall digital strategy, including aspects of preservation and the interaction with the public.

Apart from the need to adopt a digital strategy for cultural heritage, the current Cultural development plan (KEP) recognizes the necessity to "consider at its fair value the growing place of digital culture and all that it can bring in terms of cultural content, audiences, virtual identities and new networks. Whilst also reflecting on the central role of digital technologies in the creation, production and accessibility of content.”[2] And, more broadly culture’s place in an increasingly digital and data driven society.

[1] Les partis de la coalition DP, LSAP et déi gréng (2018) Accord de coalition 2018-2023, p.88

[2] Kulturentwécklungsplang eBook 1.0 - Septembre 2018, Volume 1, p.84

Last update: February, 2023

As Luxembourg is a multilingual and multicultural country, with a foreign population of 47.2% in 2021 and approx. 211,700 cross-border employees on a daily basis, intercultural dialogue is an intrinsic element of national policies, including in particular cultural policies. The interaction between some 175 nationalities within a limited territory, "which can give rise to political, social or cultural tensions, is rather perceived in and by Luxembourg as an opportunity to maintain its dual European and Luxembourg consciousness, to draw new strengths in the peaceful cohabitation of all concerned and to serve as an example for a future harmonious Europe.”[1] In Luxembourg, multiculturalism therefore designates “a model of society which respects the cultural origins of everyone, while relying on similarities and common values to ensure social cohesion.”[2]

The 2018-2023 government program insists that "public debate and reflection on the essential questions of identity(ies) and history(ies), divergences, commonalities and self-understanding of a society whose diversity, pluralism and interculturality constitute its fundamental features, remain essential for intercultural dialogue as well as effective integration and social cohesion. In this sense, “cultural diversity is one of Luxembourg's assets and is part of its identity (…). Thus, culture helps to build bridges across society, to stimulate integration and social cohesion. For this reason, intercultural events and programs that contribute to dialogue between different members of our society will be promoted. »[3]

It is therefore hardly surprising that one of the primary objectives of the current Cultural development plan (KEP) is to “link cultural diversity with intercultural dialogue by creating a virtuous circle”, aiming to “identify and encourage forms of cultural diversity that promote self-reflection, encounter and creative momentum.”[4]

Cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue also play a key role in efforts to decentralize cultural policy.

There are also many cultural events and activities that testify to multiculturalism in Luxembourg and that work in favour of intercultural exchange. “The Festival des migrations, des cultures et de la citoyenneté, the Salon du livre et des cultures (…) and the Fête de la musique are among the major cultural events that bring Luxembourg's cultural diversity to the fore. The main idea of these events is to recognize one's own culture as the fruit of cultural mixing. (…)

Luxembourg's cultural agenda displays numerous cultural events at municipal level throughout the year on the theme of cultural diversity and integration. Take as an example the Fête des cultures in the city of Dudelange (…). Dudelange also houses the Centre de documentation sur les migrations humaines (CDMH), a member of the Association of European Migration Institutions (AEMI). The CDMH places Luxembourgish and cross-border immigration and emigration in a historical, economic and social context through research, archives, conferences or colloquia and exhibitions. . (…)

The fact that there is a multitude of associations and cultural institutes representing the different communities living on Luxembourg soil, also testifies to the multicultural reality of Luxembourg society.” [5] One such association is Mir wëllen iech ons Heemecht weisen (We want to show you our homeland) which aims to stimulate intercultural dialogue between Luxembourg residents and newcomers.

Intercultural dialogue is also a unifying element of Esch2022, European Capital of Culture.

[1] Georges Hausemer (2008) A propos…du Luxembourg multiculturel

[2] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+IM-PRESS+20081127IPR43171+FR+DOC+PDF+V0//FR

[3] Les partis de la coalition DP, LSAP et déi gréng (2018) Accord de coalition 2018-2023, p.88

[4] Kulturentwécklungsplang eBook 1.0 - Septembre 2018, Volume 1, p.85

[5] http://culture.luxembourg.public.lu/Info.Monde_Integration_Festival_OMNI.10-2.html#3

Last update: February, 2023

In view of the specificities of the country and as developed in chapter 2.5.1, intercultural dialogue and openness to cultural diversity are related directly to the Luxembourg model of society. This also translates into the educational system, considering that 1) 60% of students entering primary school are of foreign origin, and that 2) Luxembourg pupils learn at least three foreign languages as part of their schooling, literacy starting in German. Education to diversity thus begins at school.

Nevertheless, one of the main conclusions of the National Education Report 2021 of the University of Luxembourg was that “the current school system does not take into account the social and cultural diversity of the country in a comprehensive way.” Thus, “for example, we continue to rely to a large extent on literacy in German alone. The multicultural and increasingly multilingual school population is only insufficiently prepared for the acquisition of written skills in this foreign language, German. (…) This is why it will be necessary to observe in the future whether and to what extent international public schools manage to manage diversity successfully. Corresponding studies are currently being carried out, and the next education report will provide for the first time empirically based conclusions in this regard. (…) In addition, pupils from socio-economically disadvantaged homes, speaking none of the languages of instruction at home or attending one of the two streams of general secondary education (ESG) are particularly vulnerable in the Luxembourg school system.”[1]

The 2018-2023 government program already stipulates that “(…) public school must continue to open up to the diversity of the population by adapting its educational and school offer to the real needs of the students. The promotion of equal opportunities remains a guiding principle that will characterize government action in the years to come. Care will be taken to give each child a fair chance to succeed and build their future. (…) In order to allow the education system to progress significantly, it is essential to take into account the specificities of the country. In compliance with the general quality objectives to be achieved, schools will be encouraged to develop approaches and concepts based on the evolution and diversity of our society.”[2] To that regard, the government agreed in May 2022 to launch a pilot project for literacy in French in four primary schools during the 2022/2023 school year.

Luxembourg also offers international private schools, as well as six European schools to be able to integrate pupils of different mother tongues into a single school. Other educational structures also offer public international programs, such as the international baccalaureate at the Lycée Athenée.

To further promote the commitment of civil society in education and make education a collective responsibility, the government created UP Foundation in 2018, the first citizen platform for exchange, pooling and support for education. A private law foundation, UP foundation “initiates all kinds of cooperation with the most diverse partners to find innovative and creative solutions. The motto that drives it: let's unite to act better![3] One of its key missions is “to assert the right of everyone to quality education and to work towards equal opportunities”.[4]

The platform, launched by the Service de coordination de la Recherche et de l’Innovation pédagogiques et technologiques SCRIPT of the ministry of Education, Children and Youth, in cooperation with the ministry of Culture, offers a range of cultural projects that aim to develop cultural education and the promotion of culture at school and to support initiatives with a cultural vocation.

[1] Thomas Lenz, Susanne Backes, Sonja Ugen, Antoine Fischbach (2021) Prêt pour l’avenir ? Le 3e rapport sur l’éducation au Luxembourg, p.12

[2] Les partis de la coalition DP, LSAP et déi gréng (2018) Accord de coalition 2018-2023, p.55-56

[3] Ministère de l’Education nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse (2018) UP FOUNDATION un coup de cœur pour l’éducation, p.2

[4] Ministère de l’Education nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse (2018) UP FOUNDATION un coup de cœur pour l’éducation, p.3

Last update: February, 2023

Overview

According to the report “Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era – country report Luxemburg” published by the,University of Luxembourg, “the media market in Luxembourg is surprisingly rich compared to its size and the number of inhabitants. The country exercises an important role in the management of international media concessions. The print sector includes five daily newspapers, one free daily newspaper, and several magazines, weekly and monthly newspapers. The TV market is dominated by RTL and there are 5 TV stations (four local and one national), but residents also have access to channels from the neighboring countries. RTL is the biggest broadcaster and has a “public service mission” but is not a “public service medium”. There are about seven private radio stations with national coverage and only one radio broadcaster (Radio 100,7) that is officially recognized as a public service medium (PSM). Internet coverage is very good across the country. This apparent diversity, however, should not hide a very large concentration (horizontal and transversal) of the market, since the majority of the national press belongs to two publishing houses while the audiovisual sector is dominated by one group (CLT-UFA). (…)

Generally speaking, fundamental protections are well implemented in Luxembourg and the media are increasingly politically independent. Notwithstanding, access to information is still limited - the context of the COVID-19 pandemic has again shown the deficiencies (…)

In addition, no legal provision aimed at limiting horizontal or cross-media concentration of news media and the laws on media ownership and transparency have serious flaws. With regards to social inclusion, access to minorities – in particular linguistic minorities (for the audiovisual sector and the PSM) and people with disabilities- is insufficient.”[1]

Women’s presence in supervising and executive positions in the media is also a critical issue. [2]

A selection of Luxembourgish laws including English translations can be accessed at the website of University of Luxembourg (https://wwwen.uni.lu/research/fdef/media_law/texts). “Among them are the Law of 1991 on Electronic Media in its codified version of 2011, the amended Regulation on European works and works of independent producers and the amended Regulation on Advertising, Sponsorship, Teleshopping and Self-promotion as well as other relevant acts in the area of data protection. The collection also includes an English version of the consolidated Law on Freedom of Expression in the Media and the consolidated regulations on quotas and advertising, the latter of which have been prepared by the uni.lu team (…) The research team of uni.lu contributes regularly to the IRIS Merlin database of the European Audiovisual Observatory by articles on updates on the Luxembourgish media law.”[3]

Media support

The law of July 30, 2021 reforms the press aid regime by setting up a more neutral and egalitarian framework for online and offline media. It foresees three different plans:

- the upkeep of pluralism, a scheme aimed in particular at current beneficiaries who have an editorial team made up of at least five professional journalists ;

- the promotion of pluralism, a scheme aimed at emerging editors who have an editorial team made up of at least two professional journalists ;

- media and citizenship education, a scheme aimed at citizen editors.

The support scheme also encourages transparency by obliging to publish the editorial line, and it also encourages the implementation of measures to ensure the accessibility of people with disabilities to content, as well as continuous training in the field of journalism and actions carried out in favour of media literacy.[4]

Rights and freedom of the press

According to article 24 of the Constitution, “[t]he freedom to manifest one's opinion by speech in all matters, and the freedom of the press are guaranteed, save the repression of offenses committed on the occasion of the exercise of these freedoms. - Censorship may never be established.” The freedom of expression in the media is ensured furthermore by the Law of 8 June 2004 on the freedom of expression in the media. Stating that “any restriction or interference must be prescribed by law, pursue a legitimate aim and be necessary in a democratic society, i.e. meet a pressing social need and be proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued”, the law also details the rights that are to be considered as inherent to the freedom of expression, as well as the duties flowing from it.

The Luxembourg association of professional journalists ALJP, on other hand, demanded long-awaited reforms in this area and deplored that, despite the announcements made in the government agreement in 2018, lines have not moved.[5] In an article published in 2021, it questioned the right of the press to access information and regretted its dependency on the government's willingness to publish or not publish information, a situation qualified as “untenable”. The ALJP criticised that it “became even worse during the Covid-19 crisis, when the press was faced with a total blocking and control of information by the government. This situation was only defused after multiple interventions by journalists and the Press Council.” [6]

In 2016, the Government had issued a first circular on the rights and duties of public officials in their relations with the press but an updated version has been published on 15 June 2022 following consultations between the Press Council, the ALJP and the Government. This updated circular is “part of the objective of continuously improving access to information held by ministerial departments, administrations and State services. In order to better organise the flow of information while respecting the response times required for journalistic work, the new circular provides for a series of measures aimed at standardising the procedure to be followed in the event of information requests from journalists.”[7]

Diversity in the media

In terms of the linguistic situation, the complexity of a multilingual country is also reflected in the media landscape: “While there are several commercial radio channels targeting this multilingual public (e.g. Radio Latina for the Portuguese speaking community or Radio ARA for the French, English, Arabic, Italian and Ukrainian speaking communities), the PSM (i.e. the sociocultural radio, Radio 100,7) and RTL (the main commercial radio and television company, that has public service missions) broadcast mainly in Luxembourgish.”[8]

Dissemination of cultural content

All media in Luxembourg have a culture desk and offer special sections dedicated to culture. Moreover, the new law of 30 July 2021 on state aid regime for professional journalism specifies that, to be eligible for this aid, press organs must "disseminate general information intended primarily for all or a significant part of the public residing in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, contribute to the pluralism of opinions and produce content relating to at least the political, economic, social and cultural fields on a national and international level". In accordance with its mission, public radio 100,7 pays special attention to “information programmes, cultural and music programmes, educational programmes, entertainment programmes and grants much time on air to the country’s socio-cultural associations. Radio 100,7 maintains numerous partnerships with cultural institutions in Luxembourg and in the Greater Region”.[9]

In June 2022, the government and the private company CLT-UFA, RTL Group signed an agreement on the provision of a public service mission in television, radio and digital activities. The agreement aims in particular to promote media education for young audiences and also provides for support measures for local film and audiovisual actors through enhanced cooperation between CLT-UFA and the Film Fund.[10]

[1] Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era – country report Luxemburg 2021) Raphael Kies,University of Luxembourg, Mohamed Hamdi University of Luxemburg, p.6

[2] Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era – country report Luxemburg 2021) Raphael Kies,University of Luxembourg, Mohamed Hamdi University of Luxemburg, p.6

[3] Media laws overview and translations, https://wwwen.uni.lu/research/fdef/media_law/texts; accessed 24 August 2022.

[4] https://gouvernement.lu/fr/actualites/toutes_actualites/communiques/2021/07-juillet/09-projet-loi-journalisme.html

[5] http://journalist.lu/fr/a-propos/

[6] http://journalist.lu/fr/assez/

[7] Adaptation de la circulaire relative aux droits et devoirs de agents fr l’État dans leurs relations avec la presse : https://me.gouvernement.lu/fr/actualites.gouvernement%2Bfr%2Bactualites%2Btoutes_actualites%2Bcommuniques%2B2022%2B06-juin%2B27-circulaire-bettel.html

[8] Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era – country report Luxemburg 2021) Raphael Kies,University of Luxembourg, Mohamed Hamdi University of Luxemburg, p.6

[9] https://www.100komma7.lu/radio-100-7

[10] https://gouvernement.lu/fr/actualites/toutes_actualites/communiques/2022/06-juin/14-bettel-convention.html

Last update: February, 2023

While the Constitution does not (yet) contain a provision on the country’s languages, a 1984 law specifies that Luxembourgish is the national language of Luxembourgers. Furthermore, it stipulates that French is the legislative language, whereas Luxembourgish, French and German are to be considered as administrative and judicial languages[1].

Due to the fact that almost half of the population is made up foreigners, there are many other language communities, the Portuguese being the largest group of foreigners in Luxembourg (approx. 15% of the total population). Thus, the ministry of Education, Children and Youth, foresees specific integrated courses in Portuguese language and culture. More generally speaking, the ministry comprises a specific department for the schooling of foreign children (Service de la scolarisation des enfants étrangers) that informs young people about the Luxembourg school system and available support measures, and also directs them to classes that best match their language skills and profile. Many other communities organise extra-school classes for children, mostly on Saturdays, often with the support of national or local authorities.

As far as culture is concerned, programmes and offers, such as for instance the yearly national literary prize, are in general open to the three official languages, as well as English. Explanations about support schemes are mostly available in French though many efforts are currently being invested into translating e.g. websites and forms into all three official languages, plus English. Though now falling into the competences of the ministry for Education, Children and Youth, the ministry of Culture initiated many years back the Lëtzebuerger Online Dictionnaire, a multilingual online dictionary that translates and exemplifies Luxembourgish words into German, French, English and Portuguese.

Following a petition with the Parliament that gained much attention with the public (nb. the right to petition is enshrined within the Constitution), a law has been passed in 2018 for the promotion of the Luxembourgish language with the aim to:

- reinforce the importance of the Luxembourgish language;

- support the use and study of the Luxembourgish language;

- encourage the learning of the Luxembourgish language and culture;

- promote culture in the Luxembourgish language.

Accordingly, the government also adopted a strategy for the promotion of the Luxembourgish language and designated a commissioner for the Luxembourg language who also coordinates a centre for the language. Part of the strategy is also to financially support cultural projects that aim to promote Luxembourgish or linguistic diversity.

In the area of media, the use of different languages is quite common, be it in written or in spoken form, although Luxembourgish is mostly used on the radio and on television. There is nevertheless also a newspaper in Portuguese (contacto) and a radio station (Radio Ara) that broadcasts its programme in more than 10 different languages.

[1] https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/1984/02/24/n1/jo

Last update: February, 2023

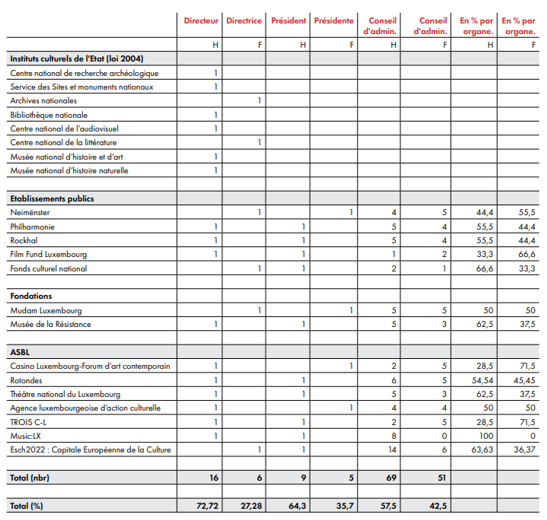

In culture, gender equality is not formally anchored in the laws and regulations relating to cultural policies, although the ministry of Culture has the ambition to "constantly ensure equal representation in the bodies of internal decision-making and promotes equal representation of women and men within external management bodies (public establishments, agreement sector, etc.).”[1]

Early 2021, the share of women and men in the management positions of cultural institutions was as follows:

Figure 1 : Female/Male representatives in leading positions of cultural institutions

Source: Ministère de la Culture, Luxembourg[2]

[1] Rapport d’activité 2020 (2021) Ministère de la Culture, p.123

[2] Rapport d’activité 2020 (2021) Ministère de la Culture, p.123

Last update: February, 2023

The KEP also welcomes political efforts to adapt the physical environment to allow as many people as possible to participate equally in culture, regardless of any physical or mental disabilities. However, "to be successful, accessibility must be considered in a plural way".[3] To this end, several works have been initiated by the ministry of Culture in the framework of the implementation of the current Cultural development plan (KEP) to develop accessibility to culture for people with special needs.

At the associative level, the Info-Handicap federation brings together some 55 organisations of and for people with disabilities in various fields, including some players in the cultural sector, such as the Coopérations association, an association for the promotion of integrated creative projects, and the Fondation EME, created on the initiative of the Philharmonie Luxembourg, whose inclusive programmes are at the crossroads of social action, music and culture.

[1] https://mc.gouvernement.lu/fr/actualites.gouvernement%2Bfr%2Bactualites%2Btoutes_actualites%2Bcommuniques%2B2021%2B01-janvier%2B19-tanson-culture-inclusive.html

[2] https://gouvernement.lu/en/actualites/toutes_actualites.gouv_mfamigr%2Ben%2Bactualites%2B2022%2Bloi.html

[3] Kulturentwécklungsplang eBook 1.0 - Septembre 2018, Volume 1, p.157

Last update: February, 2023

With almost half of the Luxembourg population being of foreign origin, "cultural integration and intercultural mediation are imperative for social cohesion".[1]

At the national level, the promotion of access to and participation in culture is seen as a powerful factor for social cohesion and is therefore an intrinsic element of cultural policy in Luxembourg. “Nevertheless, the notion of 'culture for all' is not so simple to apply. In Luxembourg, as elsewhere, not everyone participates in cultural life, not everyone has access to it and there are many reasons to this. It is therefore necessary to act on several levels at the same time to remedy this.”[2] One of the objectives in implementing the current Cultural development plan (KEP) is thus to establish an accessible and inclusive culture by developing active participation and cultural citizenship with a view to improve social cohesion.[3]

At regional and local level, culture is also seen as an "instrument for strengthening social cohesion in regions and cities.[4] The city of Esch-sur-Alzette, for instance, being one of the two municipalities so far that have adopted a local cultural development plan, specifically targets social inclusion through culture as one of the objectives in its plan entitled “Connexions”, based on the Agenda 21 for Culture. The regional cultural centres are also of special importance with regard to cultural decentralisation policies. "Regional cultural centres are becoming increasingly important due to the growing percentage of the immigrant population and the emergence of cultures specific to certain groups. The centres offer platforms, where different cultures find their place and can express themselves. They are places that different social groups (ethnic groups, youth groups, senior citizens (...) can identify with. The offers of the regional cultural centres promote the knowledge and experience cultures nearby and far away. They encourage reflection and mutual acceptance and thus contribute to social cohesion.”[5]

Some cultural institutions also signed the Luxembourg Diversity Charter, a “national commitment text proposed for signature to any organisation in Luxembourg wishing to commit to diversity promotion and management though concrete actions that go beyond legal obligations. (…) Structured around 6 articles, it guides organisations in the implementation of practices that promote cohesion and social equity through networks, workshops and conferences, involving all their employees and partners”.[6]

Best-practise cases (non-exhaustive list):

Cultur’all. Starting in January 2010, the non-profit organisation Cultur'all introduced the “Kulturpass”/Culture for All passport. With the support of the ministry of Culture, the ministry of Family, Integration and the Greater Region and the National Solidarity Fund, its aim is to offer easier access to cultural and leisure events for socially disadvantaged individuals and groups. The Kulturpass thus allows people on low incomes and applicants for international protection to participate in Luxembourg's cultural life by guaranteeing access to activities organised by the association's 75 cultural partners at a reduced rate (€1.50) or even free of charge for museums.

Fondation EME. In addition to its actions in favour of people with disabilities (see point 2.5.6), the EME Foundation's varied and inclusive programming is aimed at socially disadvantaged people and regularly offers concerts by various ensembles and groups of professional musicians, some of whom are members of the Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra, in Luxembourg's hospitals, paediatric wards and nursing homes.

HARIKO is a project of the Luxembourg Red Cross and offers creative workshops to young people between the age of 12 and 26 to be creative, to experience and to discover various forms of art, aiming particularly at young people for whom art is often difficult to access.

Creamisu. Initiated and run by Caritas Accueil et Solidarité, this is a space in Luxembourg City dedicated to artistic expression of all kinds for people experiencing homelessness.

In 2016, the artist Frédérique Buck initiated the awareness-raising campaign I am not a refugee, which aims to give a voice to refugees who have arrived in Luxembourg. [7] She also subsequently made the film film Grand H: "Three years after what is commonly referred to as the 'migration crisis' of 2015, Grand H (for Grande Humanité) addresses the conflict between migration policy and Humanity as a question.” [8]

Urban Art Esch is an artistic, educational and participatory project that the Kulturfabrik organises jointly with the city of Esch-sur-Alzette and that “seeks to turn the urban space into an arts laboratory, and hopes to develop dialogues with all audiences, and most particularly with the local community. The project also works towards social inclusion, by establishing pluridisciplinary, inter-generational, participative and inclusive workshops in parallel with realisation of the works.”

[1] Kulturentwécklungsplang eBook 1.0 - Septembre 2018, Volume 1, p.155

[2] Kulturentwécklungsplang eBook 1.0 - Septembre 2018, Volume 1, p.153

[3] https://mc.gouvernement.lu/fr/Organisation/Orientation_strategique.html

[4] Kulturentwécklungsplang eBook 1.0 - Septembre 2018, Volume 1, p.135

[5] https://www.reseau.lu/manifeste

[6] https://chartediversite.lu/en/pages/quest-ce-que-la-Diversite

[7] https://lequotidien.lu/a-la-une/im-not-a-refugee-les-refugies-du-luxembourg-se-devoilent-dans-un-livre/

[8] https://www.frederiquebuck.com/films

Last update: February, 2023

The impact of art on the well-being of citizens was particularly and widely recognised during the Covid-19 pandemic. “Beyond the simple quantifiable and quantifiable economic factor, culture remains a human need. On a societal scale, it is also a factor in the construction of citizenship, personal emancipation, collective identification and information. Figures do not allow to account for the intangible effects of the pandemic on a society deprived of cultural experiences.”[1] Convinced of the role of culture and the arts for society, the government thus reopened very quickly cultural institutions after the initial lockdown (with only a short period of closing in-between) and the ministry of Culture put in place specific support measures to relaunch culture and artistic creation in Luxembourg.

[1] Rapport d’activité 2021 (2022) Ministère de la Culture, p.33

Last update: February, 2023

The proactive development of an overall sustainable and environmentally friendly cultural policy is only at its beginnings, although a number of cultural actors already take initiatives to this regard.

In 2020, the Theater Federatioun, Luxembourg theater federation initiated a specific working group on “Ecoresponsability and sustainability” [1] to exchange ideas and experiences and defining a list of measures that has been sent to all its members for further reflexion and further ecoresponsible gestures. It also developed a proposal for pooling sets, costumes and props from the performing arts sector, proposal that has been submitted to the ministry of Culture who started working on the possible development of this idea.

In the context of the revision of the definition of museums by ICOM and of the development of a new vision by 2025, the MUDAM also put together an exchange forum around key questions relating to environmental and technological transformation, social justice and inclusion.

Esch2022-European Capital of Culture focussed on the issue of sustainability in various ways:

- by dedicating one of the four main strands of the ‘Remix’ programme to Nature: Remix Nature “encompasses both an awareness of the historical development of nature in the southern region and a call to change the way we look at nature and approach it in a socially responsible way”.[2]

- by developing a Sustainable development charter, originating from a dialogue between many local actors and the ministry of the Environment, Climate and Sustainable Development. Tying in with the UN 2030 Agenda and its 17 sustainability goals, the charter defines six objectives in view of shaping a sustainable future.

- by developing the ELO platform with the support of the ministry of the Environment, Climate and Sustainable Development. It “provides access to the various thematic guidelines, while offering concrete examples applied to various projects”.[3]

Kulturfabrik is also very active with regard to the implementation of an ecoresponsible approach:

- by adopting an environmental charter in 2014 and taking concrete measures in terms of waste prevention, reuse and recycling, and reducing water consumption, an internal working group constantly evaluating the progress made.

- by being granted the "SuperDrecksKëscht fir Betrieber®" quality label in 2010 for its environmentally friendly waste management plan.

- by acquiring the “Green Club Index” label.[4]

Likewise, the Centre Culturel Neimënster received the ESR-Entreprise responsable label, an initiative that aims at promoting social responsability among national companies so that they contribute to sustainable development and improve their competitiveness and image.

Though not specifically targeted at culture, the Green Events project of the ministry of the Environment, Climate and Sustainable Development is aimed at “reducing the ecological footprint of events organised in Luxembourg and therefore to promote eco-responsible events by informing, raising awareness and supporting organisers wishing to start organising eco-responsible events.” [5]

In a different vein, one should also mention the granting in October 2020 of the "Minett Unesco Biosphere" biosphere reserve label to the eleven municipalities of the Pro-Sud inter-municipal association in the framework of the MAB-Man and Biosphere programme. It underlines the region’s ambitions in terms of protecting its natural heritage.

[1] https://www.theater.lu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/20220330_FLAS_RAPPORTdACTIVITE_2021.pdf (page 8)

[2] https://esch2022.lu/fr/esch2022/remix-nature/

[3] https://esch2022.lu/en/sustainable-development-is-elo/

[4] https://kulturfabrik.lu/storage/app/media/Rapport_activites_2021.pdf

[5] https://www.greenevents.lu/le-projet/

Last update: February, 2023

Information currently not available.