6. Cultural participation and consumption

Italy

Last update: May, 2022

Article 9 of the Constitution of the Italian Republic states: “The Republic promotes the development of culture and scientific and technical research. It protects the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation”. Unfortunately, this promise has in the past led to efforts focused primarily on protecting the visible heritage (churches, palaces, works of art), while the promotion of culture in a broader sense has remained vague. Essential levels of cultural service provision have never been defined[1]. The complex inter-institutional system of competencies at State level and the plurality of configurations to which cultural matters are subject in regional and municipal administrations make it impossible to prescribe what the essential rights of cultural citizenship consist of and to safeguard their equal enjoyment for all.

Probably also due to a lack of aptitude for governing cultural participation, levels in Italy are particularly depressed, especially among citizens with low incomes and low levels of education and in the most disadvantaged areas of the country. Cultural participation levels vary across the spectrum of socio-economic inequality[2]. The ruling class, white-collar families and high-income retirees express the greatest intensity of cultural practice (heritage sites, live performance and cinema). At the other extreme, in a condition of cultural exclusion, are the families of retired workers, those on low incomes, and those out of work. The less active social groups in the outdoor cultural consumption are fond of the radio and, especially, television. The more active and affluent groups, on the other hand, choose to read books and newspapers more intensively.

Recent national initiatives mostly address the economic barriers to cultural consumption.

Since 2016, residents who reach the age of majority receive a €500 bonus (Bonus 18anni[3]) from the State to be used for cultural consumption (cinema, music and concerts, cultural events, books, museums, theatre, music, etc.).

Entrance to State museums, monuments, and archaeological sites (free admission in a large percentage of cases) is free for all EU and non-EU citizens under the age of 18, for several categories of visitors, as well as for all in special days and during Museum week[4].

With a more inclusive and strategic approach, the Law of 1 February 2020, n. 15 provides for the promotion and support of reading, as a means for the development of knowledge, the dissemination of culture, the promotion of the civil, social and economic progress of the country, and the training and welfare of citizens[5].

Nati per leggere - Born to Read is a project developed by the Pediatricians' Cultural Association, the Italian Library Association and the Child Health Centre, present in all Italian regions. It offers free reading activities to families with children up to 6 years of age, carried out with the financial contribution of the National Centre for Books and Reading, Regions, Provinces, and Municipalities[6].

The 2021 National Plan for Education related to Cultural Heritage (4th edition)[7] underlines the strategic role of heritage education for the cultural, economic and social recovery of the country and promotes educational actions around three strategic axes: Accessibility/Cohesion; Innovation/Creativity; Cooperation/Subsidiarity. The Region Emilia-Romagna launched in December 2021 a special experimental programme of Arts on Prescription, focused on the theatre. Children aged 3 to 8 will go to the theatre with Theatre syrup[8], 'prescribed' by their paediatrician or purchased at the pharmacy. The 'syrup' is actually a booklet, with six "prescriptions", each of which corresponds to a ticket, at the price of 2 euros, for each child and each accompanying person. Over 150 paediatricians and 234 pharmacies take part in the programme. The Syrup of theatre comprises 71 shows.

[1] Castelli G., A. Cicerchia et al. (eds.) 2018. Cultura come diritto di cittadinanza: radici costituzionali, politiche e servizi. Rome: Associazione Civita.

[2] Istat 2017. Rapporto annuale 2017. La situazione del Paese. https://www.istat.it/it/files//2017/05/RA2017_cap3.pdf.

[3] https://www.18app.italia.it/#!/

[4] https://www.beniculturali.it/agevolazioni

[5] https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/10/20G00023/sg

[6] https://www.natiperleggere.it/

[7] https://dger.beniculturali.it/iv-piano-nazionale-per-leducazione-al-patrimonio-culturale/

[8] https://www.ater.emr.it/it/news/sciroppo-di-teatro.

Last update: May, 2022

The Multipurpose survey on households “Aspects of daily life” (Aspetti della Vita Quotidiana, AVQ) is an annual survey conducted by Istat, the Italian National Institute of Statistics and carried out by interviewing a sample of 24,000 households (for a total of about 50,000 people) using a CAWI/PAPI mixed mode technique.

AVQ survey is part of an integrated system of social surveys and collects fundamental information on individual and households’ daily life, providing information on citizens’ everyday life habits and activities. Where applicable, the survey also addresses children from the age of 3 and 6.

The survey is included in The National Statistics Plan, which gathers the statistical investigations necessary for the Country.

Metadata are available from 2001 for customization and downloading[1]. Information can be sorted by year, gender, age, occupational status, region and size of urban centre. Microdata are also available for research purposes from 2013[2].

Table 3 - People who participated in or attended a certain cultural activity during the last 12 months in Italy (in % of the population, 2015, 2019, 2020)

| 2020 | 2019 | 2015° | |

| Activities heavily subsidised by the state | |||

| Theatre* | 15.7 | 20.3 | 19.6 |

| Discos, dance halls, night clubs or other dancing venues* | 16.8 | 19.1 | 20.1 |

| Dance | ND | ND | ND |

| Classical music concerts, opera* | 7.6 | 9.9 | 9.7 |

| Libraries * | 12.4 | 15.3 | 15.1 |

| Museums, exhibitions * | 27.3 | 31.8 | 29.9 |

| Monuments, archeological sites * | 25.3 | 27.4 | 23.6 |

| Cultural centres | ND | ND | ND |

| Activities without large public subsidies | |||

| Cinema * | 45.3 | 48.5 | 49.7 |

| To read books not related to a profession or studies * | 41.4 | 40 | 42 |

| In paper format (Usually use) * | ND | 36.7 | ND |

| In digital format (Usually use) * | ND | 8.7 | ND |

| Directly on the Internet (Usually use) | ND | ND | ND |

| To listen to music (Usually listen) | ND | ND | ND |

| To listen to web radio and streaming music ^ | ND | 44 | 34 |

| To read periodic publications (Usually read) * | 32.5 | 35.4 | 47.1 |

| Reading online news sites/newspapers/news magazines ^ | 49 | 44 | ND |

| To watch videos (Usually watch) | ND | ND | ND |

| Watching video on demand from commercial services ^ | 32 | ND | 10 |

| Watching video content from sharing services ^ | 56 | ND | 47 |

| Watching video content from commercial or sharing services ^ | 59 | ND | 48 |

| To watch television (Usually watch) * | 91 | 91.1 | 92.2 |

| Watching internet streamed TV or videos ^ | 60 | ND | 50 |

| Watching internet streamed TV (live or catch-up) from TV broadcasters ^ | 27 | ND | 15 |

| To listen to the radio (Usually watch) * | 56.4 | 58.8 | 57.9 |

| Directly on the Internet | ND | ND | ND |

| Playing or downloading games, images, films, or music | 35.3 | 28.7 | 52.8 |

| To use a computer (Usually use) * | 55.4 | 54.9 | 56.5 |

| Internet (Usually use) * | 73.3 | 70.4 | 60.2 |

*: Istat data from survey “Aspects of daily life”.

^: Eurostat data from survey Use of ICT for cultural purposes.

°: Eurostat data refers to year 2016.

Note: Yellow lines have been added by authors.

About data in Table 3:

- Data aboutTheatres, Discos, dance halls, night clubs or other dancing places, classical music concerts, opera, museums and exhibitions, monuments and archaeological sites, and the cinema include persons aged 6 and over by events attended at least once over the last 12 months preceding the interview.

- Book reading refers to persons aged 6 and over who have read at least one book over the last 12 month preceding the interview.

- Periodic publications reading includes persons aged 6 and over who have read newspapers at least once a week over the last 12 month preceding the interview.

- Eurostat data on ICT use include persons aged 16-74 years;

- To watch television, To listen to the radio andTo use a computerrefer to persons aged 3 years and over;

- Playing or downloading games, images, film or music and use of the Internet refer to persons aged 6 years and over.

Data are available for browsing, customizing, and downloading on the website page http://dati.istat.it/.

Data reported above can be sorted by year, gender, age, occupational status, region and size of urban centre.

Using these data Istat also calculates a yearly synthetic indicator of cultural participation in the BES (Benessere Equo e Sostenibile - Equitable and Sustainable Well-being) Report[3].

Last update: May, 2022

Table 5: Household cultural expenditure in Millions of Euros by expenditure purpose, 2020 - 2016

| Item | Audio-visual, photographic and information processing equipment | Other major durables for recreation and culture | Recreational and cultural services | Books | Newspapers and stationery | Total | |

| 2020 | Total Expenditure | 8,503 | 2,925 | 19,337 | 3,164 | 5,345 | 39,274 |

| % of total | 21.7 | 7.4 | 49.2 | 13.6 | 100.0 | ||

| 2019 | Total Expenditure | 8,419 | 2,849 | 30,473 | 3,435 | 5,768 | 50,944 |

| % of total | 16.5 | 5.6 | 59.8 | 6.7 | 11.3 | 100.0 | |

| 2018 | Total Expenditure | 8,375 | 2,950 | 29,674 | 3,481 | 5,638 | 50,118 |

| % of total | 16.7 | 5.9 | 59.2 | 6.9 | 11.2 | 100.0 | |

| 2017 | Total Expenditure | 8,260 | 2,816 | 29,438 | 3,385 | 5,695 | 49,595 |

| % of total | 16.7 | 5.7 | 59.4 | 6.8 | 11.5 | 100.0 | |

| 2016 | Total Expenditure | 7,681 | 2,719 | 29,145 | 3,348 | 5,694 | 48,587 |

| % of total | 15.8 | 5.6 | 60.0 | 6.9 | 11.7 | 100.0 | |

| var 2020/2019 | 1.0 | 2.7 | -36.5 | -7.9 | -7.3 | -22.9 | |

| Var 2020/2016 | 10.7 | 7.6 | -33.7 | -5.5 | -6.1 | -19.2 |

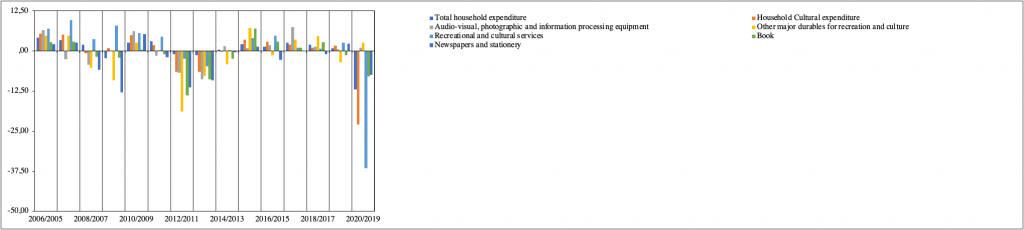

In 2020, Italian household cultural expenditure was 39,274 million Euros, the lowest since 1999. Almost half of the expenditure (49.2%) is due to recreation and cultural services, followed by audio-visual, photographic and information processing equipment (21.7%). In general, these two items are those on which Italian households spend the largest share of their cultural expenditure.

The total household expenditure in 2020 decreased by around 23% as compared to 2019 and by nearly 19% when considering 2016. Due to the exceptional conditions of the pandemic, with the venue-based cultural activities closed for long periods, in 2020 the expenditure on recreation and cultural services, newspapers and stationery, was dramatically lower than 2019. Compared to 2016, the 2020 expenditure in recreation and cultural services decreased by over 30%.

A possible effect of the long confinement at home is that in 2020 household expenditure on audio-visual, photographic and information processing equipment and on other major durables for recreation and culture maintained the growth recorded in the previous years.

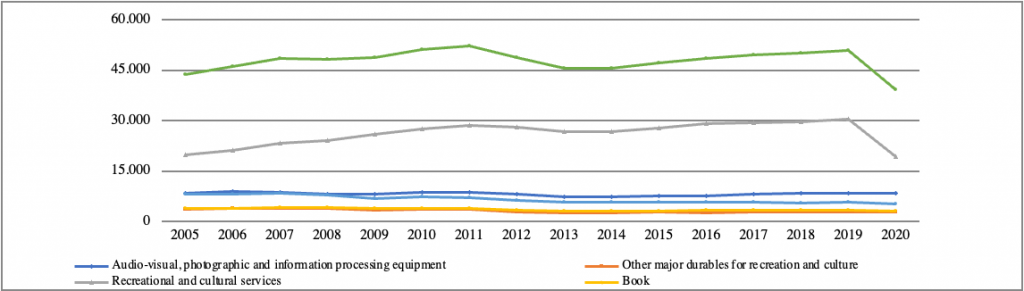

Figure 6.3.1: Household cultural expenditure in million EUR by expenditure purpose, 2005-2020

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, as expected, household expenditure for culture reduced by about 24% when compared to 2010 and by about 10% from 2005. Over the past years, household cultural expenditure had been increasing from 43,773 million Euros in 2005 to 52,067 million Euros in 2011, to fall back to 45,583 million Euros in 2015 and then increase again in the following year until 2019, when it reached nearly 51 million Euros.

In 2020 cultural expenditure represented 4.1% of total household expenditure. Between 2012 and 2019 it fluctuated between 4.6% and 4.9%. In the last 15 years, the peak of the greatest expansion of cultural expenditure was observed between 2009 and 2011, when it reached 5.1% - 5.2%. All this denotes the marginality of cultural expenditure over total household expenditure[1].

To provide a more complete picture of the characteristics of household cultural expenditure, Figure 6.3.2. shows the trend of percentage changes in total household expenditure, expenditure on culture and expenditure on culture broken down by item of expenditure.

Figure 6.3.2: Trend of percentage changes on total household expenditure, total household cultural expenditure and household cultural expenditure by purpose, 2005-2020

[1] A. Cicerchia, A. Catullo, “I consumi culturali delle famiglie” – “Household cultural consumption” in 17° Rapporto annuale Federculture 2021.

Last update: May, 2022

The provision of local cultural services varies greatly across the Country, and the State has no direct competence in this matter, which is often dealt with on a voluntary basis by the municipalities. This is why there is no nationwide statistical coverage of cultural centres, civic recreation centres, reading centres, cultural youth clubs, etc. Interrogation of the National Business Registry ASIA[1] succeeds in identifying 6,202 local units of “other entertainment and leisure activities“ (NACE code 93299) in 2019. In the 1970s and 1980s, multipurpose cultural centres, usually funded by municipalities and run by cultural associations, were frequently found in Piedmont, Lombardy, Trentino and Alto Adige, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany and Umbria, although they have become very rare. Libraries tend to replace some of their functions.

Other local actors of cultural and artistic promotion are independent marching bands[2] and singing choirs. There are about 2.500 marching bands, although there is no official registry; they are active all over the country, often even in small villages. Choral associations[3] number about 2.700, and they have similar characteristics.

ARCI – the Italian Cultural Recreational Association ARCI – is the largest and oldest Italian cultural and social promotion association, with hundreds of thousands of members and many associations, clubs, "case del popolo” (people' houses) and mutual aid societies throughout Italy. ARCI was founded in 1957 in Florence as an organisation for the defence and development of 'case del popolo' and recreational clubs. It is heir to the mutualist tradition of the popular and anti-fascist movements that helped build and consolidate Italian democracy based on the Constitution. The promotion of cultural activities related to cinema, theatre, music, visual arts, and reading is the core of ARCI's associative project. Access to and dissemination of knowledge, popular education, and expression of people's creativity are factors of civil and social growth, and essential elements of democracy and participation. ARCI develops strategies and projects in the field of lifelong learning and training and cultural welfare.

Community artistic creation is not a priority in the Italian national policies, and very few Regional administrations intervene in this domain. The Directorate General for Contemporary Creativity of the Ministry of Culture[4], however, holds an Office for Cultural and Creative Enterprises and one for Cultural creation for peripheral areas and urban regeneration.

Gai Giovani artisti Italiani[5] - The Association for the Circuit of Young Italian Artists is a body that brings together 26 local authorities (Municipalities and Regions), which has been in existence since 1989, with the aim of supporting youth creativity through training, promotion and research initiatives. The Association aims to document activities, offering services, organising training and promotional opportunities in favour of young people under 35 working in the fields of creativity, arts and entertainment. This is done through permanent or temporary initiatives that promote the circulation of information and events, both at national and international level. In 2001, GAI launched a website that is one of the most visited of its kind, with opportunities, information and resources for the art and performing arts public[6]. It also contains an online national database that is constantly updated with over 15,000 files on young creatives in the various artistic areas. The Association also carries out editorial work with the publication of catalogues and books linked to its initiatives, and carries out research projects and sector analyses.

Some regional administrations support, on a voluntary basis, some forms of cultural and artistic practice, production or protection, like literary or theatre productions in local dialects, folk music and dance, and traditional crafts.

In 2015, 45.9% of the resident population aged six years and over (around 26 million and 300 thousand individuals) expresses themselves predominantly in Italian at home and 32.2% in both Italian and their dialect. Only 14% (8 million 69 thousand people) use, instead, mainly a dialect. 6.9% use another language (about 4 million individuals; in 2006 they were about 2 million 800 thousand).

There has been a significant increase in the use of languages other than Italian and dialects within families, especially among 25-34 year-olds (from 3.7% in 2000, to 8.4% in 2006, to 12.1% in 2015).

For all age groups, the exclusive use of dialects is decreasing, even among the elderly, among whom it remains a widespread custom: in 2015, 32% of over 75s spoke a dialect exclusively or prevalently in the family (37.1% in 2006).

In 2015, 90.4% of the population had an Italian mother tongue. Compared to 2006, the estimate of those who declare themselves to be of foreign mother tongue has increased (from 4.1% to 9.6% in 2015)[7].

Several minority communities[8] in Italy, differing in language, cultural traditions and socio-economic conditions, live:

- In border regions: Valledostans, German speakers, Ladins, Slovenes. They enjoy different levels of administrative autonomy and different forms of protection;

- Dispersed throughout the territory (Arbëreshë/Albanese, Greek, Franco-Provençal, Catalan, Croatian, Occitan);

- In specific regions, as in the case of Sardinia and Friuli Venezia Giulia. Sardinian is recognised as a language to be protected. In Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Friulian is included among the minority languages.

The linguistic minorities recognised and protected by law are: Arbёreshё/Albanian, Catalan, German languages, Griko, Croatian, French, French-Provençal, Friulan, Ladin, Occitan, Sardinian, and Slovenian.

In 2007, The Ministry of Culture created a Central Institute for the Intangible Heritage[9] for the valorisation, in Italy and abroad, of the demoethno-anthropological cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, and of the expressions of cultural diversity present in the territory. It also promotes training, study and dissemination activities, collaborating with universities, public and private bodies, and national and international research centres.

The Institute promotes training, study, research and dissemination activities in collaboration with universities, research centres, and public and private bodies.

[1] http://dati.istat.it/#

[2] https://www.bandamusicale.it/bande/italia/

[3] https://www.italiacori.it/

[4] https://www.beniculturali.it/ente/direzione-generale-creativita-contemporanea.

[5] https://www.giovaniartisti.it/lassociazione

[6] www.giovaniartisti.it

[7] https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/207961.

[8] https://www.miur.gov.it/lingue-di-minoranza-in-italia

[9] https://icpi.beniculturali.it/