6. Cultural participation and consumption

Luxembourg

Last update: February, 2023

Inclusive and open cultural participation is one of the priorities of the Government’s coalition programme 2018-2023, that also states clearly that culture must be able to be truly shared by all while ensuring to include people who are a priori more distant from culture.[1] Also KEP is very vocal about the cultural participation and consumption, detailing many objectives in that respect, as well as proposing recommendations 47 to 51.

Many actions target, directly or indirectly, access to culture on many different levels, be it through specific actions for particular groups (children and young people, senior citizens, peoples with different cultural backgrounds, people with disabilities etc.) or in terms of public outreach, using all kinds of digital and non-digital formats. Addressing some of them, one can cite:

Cultural participation of people with modest income is being targeted through the setting up in 2008 of a “Kulturpass”/Culture for All passport, managed by the Cultur’All association that benefits from a support agreement with the ministry of Culture and the ministry of of Family Affairs, Integration and the Greater Region. The Kulturpass is a nominative and personal card that is free of charge and valid for two years. It grants access to partner museums without entry fee, whereas the entry tickets to dance shows, concerts, theatre plays, the film library or a festival can be bought at a reduced price of 1,50 euros.[2]

Cultural diversity being considered as one of Luxembourg's assets and part of its identity, the State aims to promote intercultural events and programs that contribute to dialogue between participants from different origins, as well as to ensure that public cultural institutions dedicate part of their program and resources to intercultural activities.[3] Some examples of numerous initiatives can be mentioned, such as the work of Centre of Documentation on Human Migrations (Centre de Documentation sur les Migrations Humaines – CDMH), Hariko, The Migrations, Cultures and Citizenship Festival, or the mateneen call by the OEuvre Nationale de Secours Grande-Duchesse Charlotte.[4]

Measures for cultural participation of people with disabilities: the ministry of Culture, in collaboration with Info Handicap, offers training on welcoming people with disabilities within a cultural institution. There are also training courses since 2020 for cultural mediation, programming and communication officers in the area of welcoming and communicating towards special needs public.[5] Nevertheless, inclusive accessibility remains a challenge.

For senior citizens, there are rather few specific measures. Noteworthy, Villa Vauban offers specific guided tours for persons who are 65+, with adapted pace of the visit and available stools and wheelchairs, if needed.[6] More generally, GERO - Kompetenzzenter fir den Alter (Gerontological Competence Center) invests in innovative approaches that positively influence the lives of elderly people in Luxembourg, proposing also cultural workshops, conferences and visits (www.gero.lu).

More recently, the ministry of Culture, together with the ministry of Justice and in collaboration with the Prison Administration have launched a call for projects aimed at associative structures to encourage the development of cultural projects offering the inmates the possibility to reconnect with a part of society, to discover or revive new means of expression, while developing their talents or passions.

Strengthening citizen participation is also one of the major aims of the cultural programme of the European Capital of Culture, Esch2022 in order to activate and involve citizens from across the region, but also to anchor citizen participation within institutional and policy thinking. To this end, Esch2022 has also signed an agreement with the Cultur'all association, in charge of promoting the Kulturpass.[7]

[1] Les partis de la coalition DP, LSAP et déi gréng (2018) Accord de coalition 2018-2023, p.84-85.

[2] https://kulturpass.lu; Accessed 22 November 2021.

[3] Les partis de la coalition DP, LSAP et déi gréng (2018) Accord de coalition 2018-2023, p. 88-89.

[4] Kulturentwécklungsplang 2018-2028, p. 155.

[5] Rapport d'activité du Ministère de la Culture 2020, p. 76. Accessible at: https://data.public.lu/fr/datasets/rapports-dactivite-du-ministere-de-la-culture/#_

[6] https://www.amisdesmusees.lu/activites-des-amis/visites-pour-seniors; Accessed 8 December 2021.

[7] Esch2022 asbl (2021) Third Monitoring Report, p. 17.

Last update: February, 2023

Until approx. 2014 and "[i]n partnership with CEPS/INSTEAD, the ministry of Culture ha[d] developed and financed the "Cultural practices in Luxembourg" programme, an observation tool aimed at measuring the evolution of the dissemination of different cultural practices and the profile of audiences over time. The analyses of the (…) programme [were] mainly carried out on the basis of data from the "Culture Surveys", carried out every ten years (1999 and 2009). It [was] the main instrument for monitoring cultural behaviours in Luxembourg, as well as by means of intermediary surveys on specific aspects and questions relating to culture (reading, music, young people, etc.).”[1]

As the authors of the 2009 synthesis stated, “The completion of a new survey on cultural practices in Luxembourg in 2009, ten years after the first of its kind at national level, [was] an opportunity to take stock of the major changes that have recently affected the conditions of access to art and culture. Overall, we see a consecration of screen culture with the rise of audiovisual media and the decline or stagnation of more traditional media. Cultural participation is also on the rise: performing arts, literature and the amateur arts are doing relatively well in the residents' leisure habits. Although the survey concerned the entire resident population, it did not allow to fill the gaps that appear between the different social categories of the population in terms of access to arts and culture.”[2]

For a small country such as Luxembourg, statistical data collection is met with many challenges. The statistical cell within the ministry of Culture has effectively stopped working in 2014 and only resumed operations in 2021. Thus, only data from the two large studies on cultural practices mentioned above is available while changes in society (migratory flows, new digital uses, etc.) have had a considerable impact on the modes of reception of works and cultural consumption, making the need for a new survey evident.[3] The fieldwork of the new large study of cultural practices (with a focus on museums) has started at the end of 2020 and the results should be available mid-2022. The ministry of Culture is also in the process of establishing a culture observatory, which will complement the work done by the statistical cell.

What partially helps this situation is that, in the framework of its impact research, Esch2022 European Capital of Culture has commissioned a 2021 study with a local market research and opinion polls institute that – while it was not its main objective – also asked questions about the cultural practices right before the pandemic started. It was a representative study of the population of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, covering 1,160 residents of various social and demographic categories.[4] As these have not been published yet, for the purpose of this publication, we mainly need to rely on data up to 2009.

Table 3: People who participated in or attended a certain cultural activity during the last 12 months in Luxembourg (in % of the population, over 3 available years)

|

|

1999 |

2009 |

|

|

|

Activities heavily subsidised by the state |

|

|||

|

Theatre |

25% |

35% |

|

|

|

Opera performances |

Data not available |

Data not available |

|

|

|

Zarzuela |

Data not available |

Data not available |

|

|

|

Dance |

9% |

17% |

|

|

|

Concerts |

38% |

57% |

|

|

|

Libraries |

14% |

24% |

|

|

|

Museums |

38% |

50% |

|

|

|

Monuments |

36% |

62% |

|

|

|

Cultural centres |

|

|

|

|

|

Spectacle de rue |

24% |

49% |

|

|

|

Cirque |

11% |

16% |

|

|

|

Exposition, galerie |

33% |

47% |

|

|

|

Activities without large public subsidies |

|

|||

|

Cinema |

50% |

66% |

|

|

|

To read books not related to the profession or studies |

51% |

68% |

|

|

|

In paper format (Usually use) |

|

|

|

|

|

In digital format (Usually use) |

|

|

|

|

|

Directly on the Internet (Usually use) |

|

|

|

|

|

To listen to music (Usually listen) |

88.6%[5] |

Data not available |

|

|

|

In a computer or directly on the Internet |

|

|

|

|

|

To read periodic publications (magazines) (Usually read) |

75% |

71% |

|

|

|

Directly on the Internet |

|

|

|

|

|

To watch videos (Usually watch) |

50.3%[6] |

50.6%*[7] |

|

|

|

Directly on the Internet |

|

|

|

|

|

To watch television (Usually watch) |

97.9%[8] |

97%[9] |

|

|

|

Directly on the Internet |

|

|

|

|

|

To listen to the radio (Usually watch) |

90.1%[10] |

90% |

|

|

|

Directly on the Internet |

|

|

|

|

|

To play videogames (Usually play) |

Data not available |

Data not available |

|

|

|

To use computer for entertainment or leisure (Usually use) |

Data not available |

** |

|

|

|

Internet for entertainment or leisure (Usually use) |

Data not available |

*** |

|

|

Source 1999 and 2009: Enquête Culture 2009 et PSELL-2/1999, Ministère de la Culture et CEPS/INSTEAD[11]

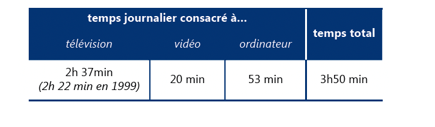

In terms of time spent in front of the screen, data from 2009 shows that 3h50min daily were spent on average daily, as shown below:

Figure 4. Time spent in front of the screen, 2009[12]

Source: Enquête Culture 2009, Ministère de la Culture et CEPS/INSTEAD.

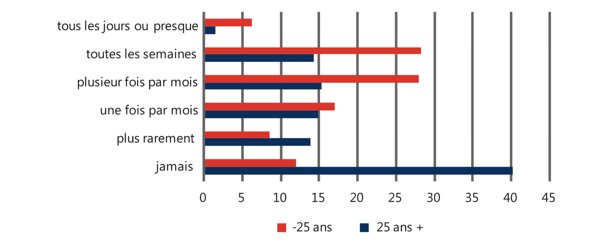

*Regarding videos, the number varies greatly depending on the age, ranging from 60% (25 year-olds and older) to 78% (younger than 25 years), as show below:

Figure 5. Consumption of videos (%), 2009 [13]

Source: Enquête Culture 2009, Ministère de la Culture et CEPS/INSTEAD

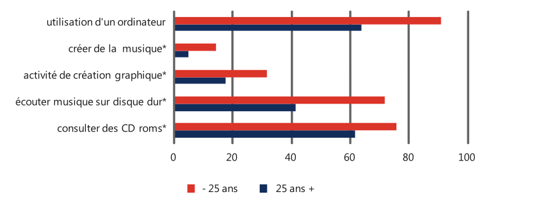

**The prevalence of different types of use of computer for culture-related purposes is presented in the following figure:

Figure 6. Pratiques numériques culturelles selon la classe d’âges (%), 2009 [14]

Source : Enquête Pratiques culturelles 2009, Ministère de la Culture et CEPS/INSTEAD. Champ : * Les utilisateurs d’ordinateur

Note de lecture : 91% des moins de 25 ans utilisent un ordinateur. Et parmi ces jeunes utilisateurs, 4% l’utilisent pour créer de la musique.

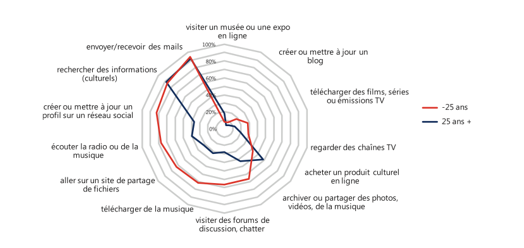

*** Personal usage of internet (at least on a monthly basis) corresponds to 69% respondednts (but this might not fully match the definition of “entertainment or leisure”). When it comes to the use of internet for communication and cultural purposes, it also varies greatly per age of the user, as shown below:

Figure 7. Les usages communicationnels et culturels des internautes au moins mensuels selon l’âge (%) en 2009 au Luxembourg

Source : Enquête Pratiques culturelles 2009, Ministère de la Culture et CEPS/INSTEAD Champ : Les usagers au moins mensuels d’Internet[15]

The percentage of population performing artistic activities has largely increased across main cultural domains from 1999 to 2009. As the authors of the study summarise: “In 2009, we observe a certain enthusiasm for amateur artistic activities that marks the development of a more expressive culture. The share of the population developing an activity related to an artistic field has thus almost doubled in ten years. A large proportion of this evolution is due to the considerable growth of photography activities during this period. This spectacular craze for photography and, to a lesser extent, cinema, can easily be explained by the arrival in force of digital technology on the market and the extremely rapid equipment of homes in this area. (…) Alongside amateur audiovisual practices, the visual arts (drawing, painting), dance, and even writing, are also increasingly favoured by the population. In the end, almost 4/5ths of the population took part in an artistic practice as an amateur in 2009, i.e. almost twice as many as in 1999. And if we exclude the taking of photographs or video films, activities that do not necessarily correspond to an artistic approach, it is still 60% of the population who invest in artistic hobbies as an amateur.”[16] An overview of this development can be seen in the Table 4 below:

Table 4: People who have carried out artistic activities in Luxembourg in the last 12 months by type of activity, in % of total population, period 1999-2009

|

|

1999 |

2009 |

|

Writing |

5% |

9% |

|

Painting, sculpture, engraving |

10% |

16% |

|

Drawing |

10% |

22% |

|

Other visual arts (pottery, ceramics, bookbinding) |

4% |

6% |

|

Photography |

25% |

68% |

|

Making videos |

14% |

26% |

|

Drama (theatre) |

3% |

4% |

|

Dance |

6% |

21% |

|

Music |

11% |

13% |

|

Singing |

5% |

5% |

Source: Enquête Culture 2009 et PSELL-2/1999, Ministère de la Culture et CEPS/INSTEAD[17]

[1] After: Bardes, J., & Borsenberger, M. (2011). Les Pratiques culturelles et médiatiques au Luxembourg. Eléments de synthèse de l’Enquête Culture 2009. Esch-sur-Alzette: CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 2.

[2]Bardes, J., & Borsenberger, M. (2011). Les Pratiques culturelles et médiatiques au Luxembourg. Eléments de synthèse de l’Enquête Culture 2009. Esch-sur-Alzette: CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 2.

[3] Kulturentwécklungsplang 2018-2028, p. 154.

[4] Jacques Maquet - Esch2022 asbl.

[5]Aubrun, A., Borsenberger, M., Hausman, P., & Menard, G. (2006). Les pratiques culturelles au Luxembourg. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 26.

[6]Aubrun, A., Borsenberger, M., Hausman, P., & Menard, G. (2006). Les pratiques culturelles au Luxembourg. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 24.

[7] Borsenberger, M. (2014). Les pratiques culturelles des digital natives au Luxembourg. La culture de l'écrit : la presse et les livres. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 11.

[8]Aubrun, A., Borsenberger, M., Hausman, P., & Menard, G. (2006). Les pratiques culturelles au Luxembourg. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 24.

[9]Lamour, C., & Lorentz, N. (2013). Nationalités et pratiques télévisuelles au Luxembourg : une approche du "vivre ensemble" dans la mosaïque européenne. CEPS/INSTEAD, see Table 2 on p. 7.

[10]Aubrun, A., Borsenberger, M., Hausman, P., & Menard, G. (2006). Les pratiques culturelles au Luxembourg. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 24.

[11]Bardes, J., & Borsenberger, M. (2011). Les Pratiques culturelles et médiatiques au Luxembourg. Eléments de synthèse de l’Enquête Culture 2009. Esch-sur-Alzette: CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 10.

[12] Bardes, J., & Borsenberger, M. (2011). Les Pratiques culturelles et médiatiques au Luxembourg. Eléments de synthèse de l’Enquête Culture 2009. Esch-sur-Alzette: CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 5.

[13] Borsenberger, M. (2014). Les pratiques culturelles des digital natives au Luxembourg. La culture de l'écrit : la presse et les livres. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 11.

[14] Borsenberger, M. (2014). Les pratiques culturelles des digital natives au Luxembourg. La culture de l'écrit : la presse et les livres. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 15.

[15] Borsenberger, M. (2014). Les pratiques culturelles des digital natives au Luxembourg. La culture de l'écran : pratiques multimédia et numériques. CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 14.

[16] Bardes, J., & Borsenberger, M. (2011). Les Pratiques culturelles et médiatiques au Luxembourg. Eléments de synthèse de l’Enquête Culture 2009. Esch-sur-Alzette: CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 10.

[17] Bardes, J., & Borsenberger, M. (2011). Les Pratiques culturelles et médiatiques au Luxembourg. Eléments de synthèse de l’Enquête Culture 2009. Esch-sur-Alzette: CEPS/INSTEAD, p. 11.

Last update: February, 2023

Mean household expenditure on cultural goods and services as a share of total household expenditure in Luxembourg belonged to some of lowest in the EU at 2.1% (versus 2.9% EU-28 average, 2015).[1] When measured in purchasing power standards (PPS), an artificial currency unit that takes account of the price level differences between EU Member States, Luxembourg households had some of the highest levels of expenditure on cultural goods and services, with its households spending around 1 000 PPS.[2]

Luxembourg Household Consumption Expenditure on Recreation and Culture averaged 4,126.519 EUR from Dec 2005 to 2016, with 12 observations. The data reached an all-time high of 4,293.690 EUR in 2007 and a record low of 3,930.270 EUR in 2005.[3]

National statistics provide aggregate numbers of spending on culture and recreation over the years, as presented in Table 5 below:

Table 5: Household Final Consumption Expenditure by function (current prices) (in millions EUR) 1995 – 2020 - Recreation and culture-related lines only[4]

|

Years |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2020 |

|

Recreation and culture (CP090) |

599.3 |

720.5 |

857.3 |

1 101.2 |

1 263.7 |

1 066.1 |

|

Other major durables for recreation and culture (CP092) |

22.2 |

16.3 |

18.1 |

31.4 |

43.0 |

23.8 |

|

Recreational and cultural services (CP094) |

117.1 |

160.1 |

225.5 |

334.3 |

449.9 |

385.1 |

Source: STATEC, Household Final Consumption Expenditure by function (current prices) (in millions EUR) 1995 – 2020

Table 6: Luxembourg household cultural expenditure by expenditure purpose, 2015[5]

|

Items / Field / Domain |

%, share of all household cultural expenditure |

|

Television and radio fees, hire of equipment and access-ories for culture |

13.1 |

|

Infomation processing equipment |

18.3 |

|

News-papers and periodicals |

13.1 |

|

Books |

14.3 |

|

Cinemas, theatres, concerts |

7.9 |

|

Reception, recording and |

9.4 |

|

Stationery and drawing materials |

9.3 |

|

Musical instru-ments |

3.3 |

|

Recording media |

3.9 |

|

Photo-graphic and cinema-tographic equipment |

3.4 |

|

Services of photo-graphers and performing artists |

1.1 |

|

Museums, libraries, zoological gardens |

0.4 |

|

Reception, recording and |

1.8 |

|

Repair of audio-visual, photo-graphic and infor-mation processing equipment |

0.8 |

Source: EUROSTAT Culture statistics - household expenditure on culture 2015

[1] Eurostat (2019) Culture statistics- household expenditure on culture, 2015; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Culture_statistics_-_household_expenditure_on_culture&oldid=471060; Accessed 1 December 2021.

[2] Eurostat (2019) Mean household expenditure on cultural goods and services, 2015; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Mean_household_expenditure_on_cultural_goods_and_services,_2015_CP2019.png; Accessed 1 December 2021.

[3] CEIC, based on national portal of statistics in Luxembourg, Luxembourg Household Consumption Expenditure: Avg: Recreation and Culture; https://www.ceicdata.com/en/luxembourg/household-consumption-expenditure/household-consumption-expenditure-avg-recreation-and-culture; Accessed 1 December 2021.

[4] STATEC, Household Final Consumption Expenditure by function (current prices) (in millions EUR) 1995 – 2020; https://statistiques.public.lu/stat/TableViewer/tableViewHTML.aspx?ReportId=13144&IF_Language=eng&MainTheme=5&FldrName=2&RFPath=22; Accessed 1 December 2021.

[5] EUROSTAT Culture statistics - household expenditure on culture; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Culture_statistics_-_household_expenditure_on_culture&oldid=574136#Household_cultural_expenditure_-_level_and_structure

Last update: February, 2023

KEP has put in light several challenges linked to the regional, local and community-driven cultural efforts.[1] According to the municipality code, culture is not one of the obligatory missions of a municipality, resulting in a very unequal cultural and artistic offer across the country. The regional cultural centres and individual municipalities play an important role in the cultural landscape of the country, but the often top-down policies do not always reflect this enough. Moreover, the financing of the regional and local cultural efforts often does not sufficiently match the actual cultural impact these activities have even on a national scale, e.g. through organisation of important festivals. This is combined with challenges concerning insight and statistics on the regional and local levels. In response, KEP proposed a number of objectives and recommendations 29-31 for the 2018-2028 policy. The ministry of Culture is also currently undertaking a mapping on regional and local cultural centres and culturally-used facilities.

An important player is the Réseau Luxembourgeois des Centres Culturels Régionaux (http://reseau.lu), a non-profit network organisation of ten decentralised regional cultural centres founded in 2008. Even though the members differ a lot when in size and facilities, they all are locally embedded, have an important regional influence and are being subsidized by their respective municipalities and by the ministry of Culture. The network’s objectives are laid down in a manifesto : "The centres are responsible for "providing the basic supply" of culture to the population in the decentralised regions (= proximity), by offering a diversified programme with possible specialisations in certain fields. In doing so, the centres fulfil different tasks

- to provide platforms for the expression of different cultures;

- to create links between local culture, regional roots and interregional cultural productions;

- to provide opportunities for identification for a wide range of people and thus help social cohesion;

- to stimulate dialogue;

- to professionalise cultural life;

- to provide forums for young art;

- to be understood as actors in regional development and provide input to the socio-educational, socio-cultural and economic development of the region;

- to encourage individual development through their programmes.[2]

Besides the work of regional cultural centres, other actors engage more specifically in the mitigation through culture of the effects of social exclusion and societal crises. For instance, Hariko (www.hariko.lu), a service of the Luxembourg Red Cross for young people between the age of 12 and 26, “aims to offer access to different forms of artistic expression to young people from underprivileged backgrounds, to young people attracted by art but also to refugees, migrants and asylum seekers”. In another example, the CULTURE_UP programme by the UP_FOUNDATION “offers educational workshops to various institutions that support vulnerable children and young people, aiming to strengthen the individual through culture. This programme is offered to institutions, associations, or initiatives that work with vulnerable children and young people and is tailored to the respective institution's needs. These educational activities will bring out the potential and creativity of children and young people who have little access to culture and will help them discover their passions.”[3] Furthermore, following the call for projects launched by the Œuvre Nationale de Secours Grande-Duchesse Charlotte and Esch2022, three new cultural projects will be able to develop: “Bâtiment IV” in Esch-Schifflange, “Cultural Hub + / Vestiaire” in Dudelange and FerroForum & "Kamelleschmelz".

Recently, some investments have also been in made in the ‘cultural third places’. A joint initiative of the Œuvre nationale de secours Grande-Duchesse Charlotte and Esch2022 aims to support transdisciplinary cultural projects that will develop in areas such as brownfields, abandoned spaces or in the heart of the city, in the form of collaborative ecosystems. Following a call for projects, new cultural projects able to develop as third cultural places are: “Bâtiment IV” in Esch-Schifflange, “Cultural Hub + / Vestiaire” in Dudelange and FerroForum & "Kamelleschmelz".

Finally, more and more attention is being paid to active citizen participation in culture - including difficult to reach populations. As an example, citizen participation is at the very core of the Esch 2022 strategy, as reflected in everything from the project’s objectives, to impact indicators, call for project evaluation criteria and the thematic focus itself. The Impact Lab was commissioned to develop a Toolbox for citizen participation in culture for Esch2022-involved municipalities. The toolbox includes 27 detailed and practical approaches to citizen participation in culture, engaging specific groups such as children and youth, seniors, migrants, disabled people etc., focusing on specific locations e.g. ‘forgotten’ neighbourhoods, as well as more cross-cutting approaches such as participatory budgeting, audience-as-artist, or blurring the boundaries among different roles, to name just a few examples. Some municipalities are dedicating significant effort to enhancing and better understanding citizen participation in culture. These include for instance Esch-sur-Alzette (one of the few municipalities with its own cultural strategy, carrying out numerous studies and actions in this respect), or Sanem, which has commissioned a strategy and toolbox for the engagement of their own citizens in cultural policymaking.

[1] Kulturentwécklungsplang 2018-2028, p. 136.

[2] https://www.reseau.lu/manifeste; Accessed 23 November 2021.

[3] https://upfoundation.lu/projects/culture_up/?lang=en; Accessed 18 November 2021.